Module Nineteen

The Prison Letters

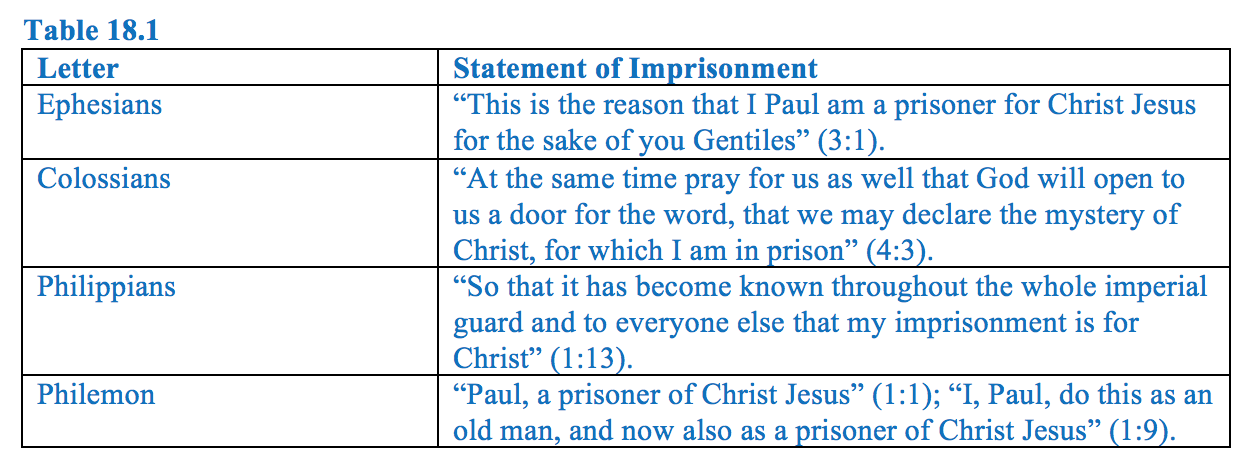

In this chapter, students are introduced to a category that traditionally consists of four letters, called “Prison/Captivity Letters” or “Prison/Captivity Epistles.” The main reason for this designation is that each contains a direct statement attributed to Paul informing his audience that he is a prisoner at the time of writing (see Table 18.1). The Prison Letters consist of Ephesians, Colossians, Philippians, and Philemon.

Table 18.1

Statements about Paul’s imprisonments are also found in Acts, which refers to a two-year imprisonment in both Caesarea (23:33-26:32) and Rome (28:16, 30) and the possibility of a third one in Ephesus (19:23-40; 1 Cor 15:32). Placing the Pauline statement of imprisonment within the framework of Acts is, however, both tenuous and tentative. Not only must judgments be made about its theological agenda, genre, and the accuracy of its chronology, but one must also be prepared to defend the historical accuracy of Acts from start to finish (see Module 13). Additionally, Paul may have been incarcerated more often than Luke records. As part of a summary statement on his sufferings, Paul refers to “far more imprisonments, with countless floggings” in 2 Cor 11:23. Outside the New Testament, Clement of Rome records at the end of the first century that Paul was in prison seven times (1 Clem. 5:6) and the Acts of Paul, probably written in the middle of the second century, claims that he was imprisoned in Iconium (3.17–20), Ephesus (6), Philippi (8), and Rome (11). While reconstructions of Paul’s imprisonments must take Acts and Clement into account, they cannot take priority over Paul’s own statements. In the end, the exact number of incarcerations is uncertain.

Categorizing these four letters as Prison Letters is effective and convenient in an introduction like this, but may run the risk of overshadowing two common impediments. First, the authorship of Ephesians and Colossians is frequently contested by scholars. If Paul did not write them, then they were probably not composed in prison. Scholars who hold that Paul did not write Ephesians or Colossians argue that the author uses an imprisonment setting to help readers receive the letters as testimonies of one who is suffering for the faith. Second, traditionally this category has not included 2 Timothy, which is commonly included among the “Pastoral Letters.” Despite the problems associated with its authorship, it nevertheless situates Paul in prison in Rome (1:16-17).

We begin with Ephesians and Colossians, the two prison letters whose authorship is often disputed.

The ruins of a prison at Philippi

Ephesians

18.1 Introduction

Like Romans, the letter to the Ephesians is regarded as one of the most significant Pauline writings on Christian thought and spirituality. Alongside its theological acclaim and influence throughout the history of Christianity, modern scholarship has debated its authorship. As a result, it has commonly been included among the “disputed” or “deutero-Pauline” letters.

The Aegean Sea and area

The city of Ephesus, which is one of the most well-preserved archaeological sites in the world today, is located in the western part of modern-day Turkey. In the first-century CE, it was a leading commercial center in the Roman province of Asia and was commonly called the neokoros (often given to a warden of a temple) of the region, which implied prestige in comparison to other cities. Festivals, rituals, and other acts of worship in honour of the Emperor were frequent occurrences, which attracted travelers from around the Empire. Its stature among the cities of Asia Minor is reflected in its 25,000-seat amphitheater, which is well preserved today. It was also renowned for its temple dedicated to Artemis, which is regarded as one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. While the goddess Artemis was well known in antiquity, she played a prominent role among the Ephesians who were proud of their loyalty and devotion to her. Artemis was a mother goddess, who was regarded as a provider of fertility and as an overseer of children.

The Amphitheater in Ephesus

Artemis was easily distinguished by the many spheroid shapes on her chest. Theories vary, but they are thought to be breasts, eggs, bull testicles, or even gourds (which were known in Asia as fertility symbols for centuries). Artemis' robe is always decorated with lions, leopards, goats, griffins, and bulls, which represent Artemis' title of Lady of the Animals.

For detailed photographs of the statue, see http://www.livius.org/articles/religion/artemis-of-ephesus/

According to Acts, Paul briefly visited the city on his second missionary journey (18:19–21). He returned during his third journey (19:1–41; cf. 20:17–38) and stayed for two to three years (19:10; 20:31). If Luke’s chronology is accurate, Paul would have resided in Ephesus in the early-to-mid 50s, from where most likely he wrote 1 Corinthians. Paul’s experience in Ephesus does not appear to have been comfortable, though (1 Cor 15:32; 2 Cor 1:8). In 1 Cor 16:8–9, Paul indicates that he faced many enemies in Ephesus. Regardless, he saw it as an opportunity to spread his message.

18.2 Authorship

The authorship of Ephesians is frequently contested. Some scholars argue that the real author was aiming to imitate Paul’s style in an attempt to communicate his intention if he were still alive. Other scholars are less charitable with the aim of pseudonymity, suggesting that the motivation was to undermine Paul’s thinking by writing in his name (see Module 15.5.4).

The widespread skepticism is largely based on two central observations. The first is the similarity between Ephesians and Colossians. And the second is the distinctiveness of Ephesians when compared to the undisputed letters of Paul. Let’s take a closer look at each.

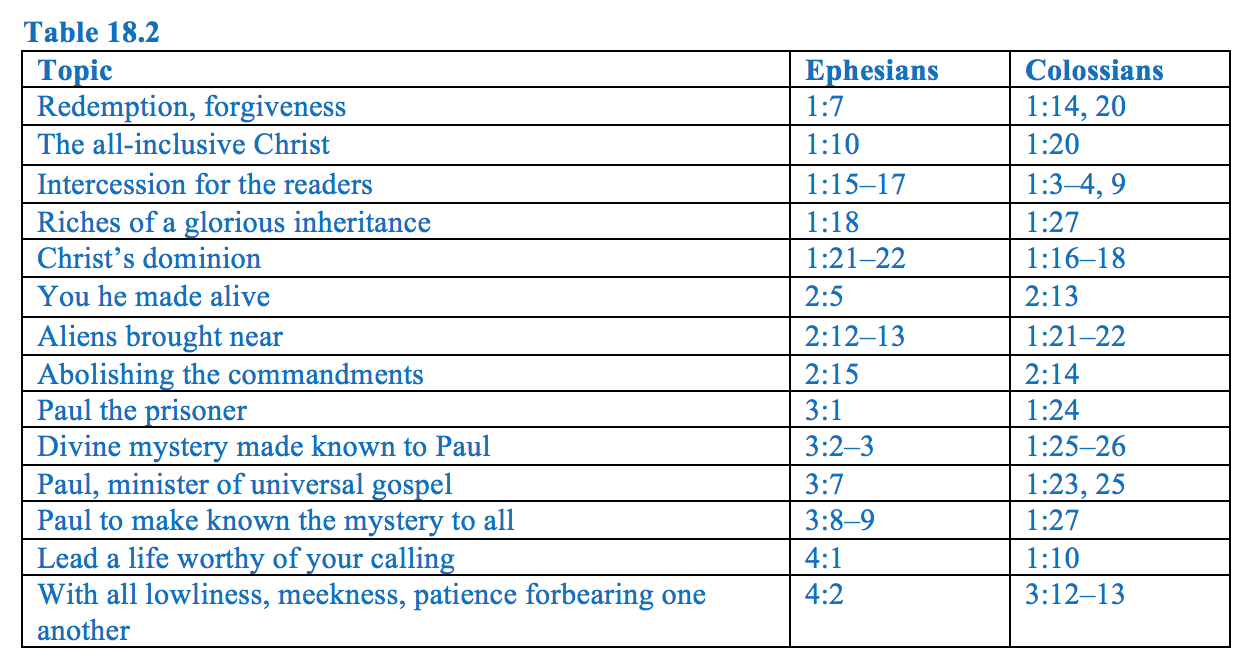

18.2.1 Similarities with Colossians

The similarities are extensive. Somewhere between one-half and one-third of the 155 verses in Ephesians have close parallels to the material found in Colossians. In many cases, these parallels occur in the same order of presentation. A few passages are very close in wording (E.g. Eph 1:4 cf. Col 1:22; Eph 1:15 cf. Col 1:4; Eph 6:21–22 cf. Col 4:7–8). In addition to their common language, the similarities extend to both themes and theological content as seen in the following table taken from R. E. Brown’s, An Introduction to the New Testament (New York: Doubleday, 1997) 630.

The remarkable similarities between Ephesians and Colossians have generated many explanations about their interdependence. Most scholars argue that Colossians was written first and that whoever wrote Ephesians was familiar with its contents. Ephesians tends to present general reflection on more detailed material in Colossians. Interdependence, of course, raises immediate questions about authorship, especially for Colossians. Though a more detailed discussion is found below in 18.7, the common proposals can be summarized as follows:

1. Paul wrote Colossians first as a specific letter to a particular church, and then wrote Ephesians as a more general letter dealing with the same subject matter.

2. Paul wrote Colossians and subsequently someone else later used it as a template for writing Ephesians in Paul’s name.

3. Paul did not write Colossians or Ephesians; instead, the same pseudonymous author wrote both letters.

4. A pseudonymous author wrote Colossians, and subsequently a different pseudonymous author used Colossians as a template for writing Ephesians.

18.2.2 Distinctiveness of Ephesians

When compared to the undisputed letters of Paul — Galatians, 1 Thessalonians, Philippians, 1 & 2 Corinthians, and Romans — Ephesians has many differences. (see below Info Box 18.1). Some of these are minor, whereas others are significant theologically. For example, in the undisputed letters, the foundation to Paul’s thinking about salvation is rooted in an eschatology that will be realized in the imminent return of Jesus. When Paul uses the noun “salvation” or the verb “to save” in the undisputed letters, he is usually speaking about a restored relationship with God that is often set in the near future or is in the process of being completed. For Paul, salvation is something that will happen when Jesus returns and delivers his people (see Rom 5:9–10; 1 Cor 3:15; 5:5). A possible exception is Rom 8:24 where Paul says “we were saved,” though it is used in the context of a future redemption. The past tense most likely refers to the reception of the gospel message. In Ephesians, however, salvation is not guided by an eschatological hope, for the followers of Jesus have already been saved (2:5, 8) and raised with Christ (2:6). There is also no mention of Christ’s return, though there are two references to the coming age(s) (1:21; 2:7) which may refer to the so-called church age.

The writing style of Ephesians also differs from the undisputed letters of Paul. While some of the subtle divergences can be attributed to a different amanuensis or to a different purpose, there are other divergences that are clearly intentional and significant. They are obvious, especially when read in the Greek. For example, Ephesians has very long sentences compared to the undisputed letters. It features approximately 100 complete sentences, nine of which are over fifty words in length, such as the opening thanksgiving in 1:3–14. Compared to Philippians, which is a similar length, only one sentence is over fifty words. Galatians has 181 sentences and only one is over fifty words in length. It appears that Paul tended to write or dictate more succinct sentences.

Info Box 18.1: Examples of Specific Distinctions of Ephesians.

In addition to the examples above, here is a broader list of differences. In Ephesians,

• we find a repetitive use of adjectives and synonyms (e.g. 1:19 uses four words for “power”).

• the author prefers to use “devil” (4:27; 6:11) instead of “Satan” (Rom 16:20; 1 Cor 5:5; 7:5; 2 Cor 2:11; 11:14; 12:7; 1 Thess 12:18).

• the author prefers “kingdom of Christ and God” (5:5) rather than “kingdom of God” (Rom 14:17; 1 Cor 4:20; 6:9, 10; 15:50; Gal 5:21; 1 Thess 2:12).

• one is “saved” by faith (2:5, 8) rather than “justified” by faith (Rom 3:28; 5:1; Gal 2:16; 3:24).

• the church is built on the foundation of the Apostles and Prophets, with Christ as the cornerstone (2:19–20) rather than on the foundation of Christ alone (1 Cor 3:10–11).

• marriage serves as a lofty example (5:21–23) rather than a recommendation for controlling lust (1 Cor 7:8–9).

• the law is said to have been abolished by Christ (2:15) rather than still applicable (Rom 3:31).

• the reconciliation of Jews and Gentiles is a present reality (2:11–18) rather than as a future hope (Rom 11:25–32).

• exaltation of believers to heaven is a present reality (2:6) rather than a future hope (1 Cor 15:23; 1 Thess 4:16–17).

18.2.3 Authorship Scenarios

The modern debate about the authorship of Ephesians has led to three major options: Paul himself, an immediate follower of Paul, and a later follower of Paul. Let’s consider each proposal in more detail.

1. Ephesians Was Written by the Apostle Paul

In this scenario, which represents a traditional view, Paul first wrote Colossians as a letter dealing with specific issues facing Christ-followers in the city of Colossae. While the letter was still fresh in his mind, it served as a pattern for Ephesians which addresses a more general audience, most likely as a circular letter intended for several communities in Western Asia Minor. Some have compared this hypothetical relationship between Colossians and Ephesians to the relationship between Galatians and Romans, proposing that the arguments in Galatians serve as a pattern for the composition of Romans.

Scholars who endorse this scenario often attribute the distinctive features of Ephesians to changing contexts and circumstances. For example, Paul may have granted his amanuensis much more latitude in the construction of the letter. Additionally, it is also proposed that Ephesians simply reflects a development in Paul’s thinking.

2. Ephesians Was Written by One of Paul’s Followers after His Death

Another proposal pictures the author as someone who wanted to express what Paul would have said if he was still alive. One version holds that Ephesians is simply a posthumous publication, written soon after Paul’s death. Another version posits that Ephesians was written a decade or two after Paul’s death by a follower who felt authorized to speak for Paul, as a way to honor him or as a way to keep his tradition alive. In either case, the author is often viewed as one of Paul’s foremost disciples expressing, as some have said, the “crown of Paulinism.” He is regarded as a brilliant thinker and eloquent writer who maintains continuity with the undisputed letters while at the same time incorporating his own distinctive features.

While the identity of this follower is lost, there is no shortage of potential candidates. Since Timothy is listed as a co-author of Colossians, his name is at the top of the list. Other proposals are more creative, such as Onesimus, the runaway slave mentioned in Philemon. Interestingly, Ignatius of Antioch (d. 107) mentions a certain Onesimus who was a bishop in Ephesus. Another name that has surfaced is Luke the physician, who is associated with the authorship of the Gospel of Luke and Acts. He was said to have been with Paul during his time in prison in Rome (Col 4:14; Phil 24). Still others point to Tychicus, a spokesperson for Paul and the presumed bearer of both Colossians and Ephesians (Col 4:7; Eph 6:21).

3. Ephesians Was Written by a Later Admirer of Paul Who Had Not Known Him.

According to the third scenario, Ephesians was written by someone who used Paul’s name to promote his own ideas. While the intent may have been self-serving and even malicious, it could also be viewed as honouring Paul by giving him credit for the forger’s ideas. Whatever the original intent, the author is viewed as promoting an institutional form of Christianity, which some have called “early catholicism.” As a result, advocates of this scenario often argue that Ephesians has more in common with the ideas of second-century church leaders than that of Paul.

While Ephesians gained acceptance almost immediately as a genuine letter of Paul, which would support the first scenario, it may have done so because it promoted ecclesiastical structure and authority that would have appealed to persons in positions of power (e.g. 2:20; 3:5; 4:11). Regardless, Ephesians is viewed as a window into how later Christian generations developed Paul’s ideas.

These three views about the authorship of Ephesians have led to varying interpretations of the letter because they situate it in different social contexts. Nils Dahl’s summary of how Ephesians has been read over the years is well phrased. He writes that Ephesians has been read as “the mature fruit of Paul’s thought,” “an inspired re-interpretation of Paul’s thought,” or “the beginning distortion of Paul’s thought.” (“Ephesians,” in Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible: Supplementary Volume, 268)

18.3 Purpose and Audience

Purpose

There is general consensus on the purpose of Ephesians. The writing is meant to encourage Gentile Christians of their new identity as the people of God. The author writes that while they were once alienated from God, they have been united with “Israel,” God’s household, through the work of Jesus Christ (2:1–22). Old barriers between Jews and Gentiles, which are blamed on the Law, have been “abolished” in the reconciling process that is effected by the death of Jesus (2:11–18). The aim of the first half of the letter is to show the unity of Jews and Gentiles, which is called the mystery of the Gospel that was hidden from previous generations (3:1–13). The second half of the letter is ethical, instructing the recipients to live as a unified people (chapters 4–6).

Audience

In most English translations, the letter is addressed to “the saints who are in Ephesus and are faithful in Christ Jesus” (1:1). But the words “in Ephesus” are not found in the earliest manuscripts. Most textual critics conclude that the words were not part of the original version, but were added by a scribe after the letter was already in circulation. If this was the case, then Ephesians was originally meant to be a circular letter, sent to several Pauline churches, to the “saints who are faithful in Christ Jesus.” When the letter was received, it was likely copied by the recipients and sent on to its next location, one of which was Ephesus. A scribe there likely added “in Ephesus” so that when the letter was read, it would be received more personally. This process of transmission may also explain why Marcion (see Module 5.2), a second-century philosopher, refers to this letter as “the letter to the Laodiceans.”

The first page of Ephesians in Codex Sinaiticus, The additions in the center margin, the words ΕΝ ΕΦΕϹW [pronounced en e-phes-ō] are the Greek for “in Ephesus.”

On the first page of Ephesians in Codex Sinaiticus, the oldest complete manuscript of the New Testament, notice that the first verse has been corrected in the margin. The letter was originally addressed “to the saints,” but a later scribe made the address more specific by inserting the phrase “who are in Ephesus.”

The manuscripts have three variant readings, one with and two without “in Ephesus.” The first reads “to the saints, to those being in Ephesus” and faithful (A and D [fifth century], and the majority of other MSS).

The second reads “to the saints, to those being also faithful” (B and Sinaiticus [early fourth century]).

The third reads “to the saints being also faithful” (46 [ca. AD 200]).

18.4 Genre

It may be surprising to read that Ephesians is not always regarded as a letter. While it may resemble one, several scholars have argued for alternative genres to which an epistolary opening (1:1–2) and closing (6:21–22) have been attached. If so, then it is likely that the Ephesian “bookends” were borrowed from Colossians (see Table 18.3).

Paul, an apostle of Christ Jesus by the will of God, and brother Timothy,

To the saints and the faithful brothers in Christ in Colossae.Grace to you and peace from God our Father.

Paul, an apostle of Christ Jesus by the will of God,

To the saints who (are in Ephesus and) are also the faithful in Christ Jesus:

Grace to you and peace from God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ.

Tychicus will tell you everything about me; he is a beloved brother, a faithful minister, and a fellow servant in the Lord. I have sent him to you for this very purpose, so that you may know how we are and that he may encourage your hearts;

So that you also may know how I am and what I am doing, Tychicus will tell you everything. He is a beloved brother and a faithful minister in the Lord. I am sending him to you for this very purpose, to let you know how we are, and to encourage your hearts.

A few examples of alternative proposals are helpful for understanding why genre has been a debated issue. First, Marion Soards proposes that Ephesians is akin to a theological tractate in a standardized Pauline form that collects Paul’s thoughts and teachings and presents them in a condensed package (The Apostle Paul, 153). A case in point is Eph 2:8-10, which summarizes salvation by faith. Those who disagree with Soards point out that Ephesians does not summarize most of Pauline thought in the undisputed letters. It has also been pointed out that Soards’s proposal does not account for the unique theological concepts in Ephesians, such as unity, triumphal ecclesiology, and an exalted Christology (see Info Box 18.1).

Second, some have argued that Ephesians is a speech or a type of lecture since it is congratulatory in tone through expressions of praise. As such, it is an enthusiastic evaluation of what has been achieved in Christ for all Christians and indeed for the whole universe. Rather than appealing to anyone or any main issue, the author encourages growth in the Christian life by giving general exhortations.

Third, based on references to communal prayer, Ephesians has been understood as a homily or guide for liturgical practices. For example, John Kirby (Ephesians: Baptism and Pentecost) argues that the baptismal language in 1:13–14; 4:5, 30; 5:8, 26 is an expanded teaching for those who have already been baptized. Additional support is found in the close relationship between Ephesians and 1 Peter, which is often thought to be a baptismal homily. Others have suggested that Ephesians was understood liturgically, perhaps as part of a Eucharist practice, since the first half starts and ends with a doxology.

Regardless of the various options, Ephesians was meant to be a general address for widespread distribution. Perhaps at one point it served as a document for liturgical purposes before or after it was transformed into a letter.

18.5 Themes

18.5.1 The Mystery of God’s Plan Now Revealed

The Greek term mystērion (“mystery”) occurs in Ephesians six times (1:9; 3:3, 4, 9; 5:32; 6:19). For the author, a mystery is not a puzzle that needs to be solved, but rather it is something hidden that cannot be known apart from divine revelation. The revealing of the mystery is announced in 1:9–10 as God’s plan to reunite all things in heaven and on earth, which for the author is in the process of unfolding. Of particular importance is the unification of Jews and Gentiles who are together identified as a new humanity (2:15). The process of revealing the mystery begins with Paul, who receives the divine plan directly from God and announces it to the church (3:1–5, 8–9; 6:19), which in turn reveals it to the world (3:9–11).

God’s plan, which was “hidden for ages” (3:9), is realized in Christ in two stages. The first stage is the death of Jesus, which has effected the unification of Jews or Gentiles and placed humanity on an equal footing before God (1:7; 2:4, 13. 16–18). Exactly how Jesus’ death accomplishes this is illusive, but it most likely links Jesus’ identity and obedience with a new basis for understanding humanity. Those who are faithful are no longer identified as being in sin, perhaps in association with Adam. In the process, the law which divided the ethnic groups, has now been abolished through the cross (2:14–15). The second stage is the exaltation of Christ, which takes place through his resurrection and subsequent ascent to heaven where he rules over all powers and principalities (1:19–22), giving hope to all people who have been formerly captive in sin, led by the spirit of disobedience, and metaphorically dead (1:21–22; 2:1–5; 4:8; 6:12). Christ’s new exalted life is again linked with his followers, who are assured of participating in it even while they are alive.

The author points to two signs that confirm the realization of God’s plan. The first sign is the guiding presence and “seal” of the Holy Spirit (1:13), and the second is the unity of the church (4:4–6, 11–16); especially the unity of Jews and Gentiles (2:11–21). These signs indicate to the cosmic powers that the mysterious plan of God has taken hold (3:10–11).

Info Box 18.2: Spiritual Beings

In Ephesians, we get a glimpse into the widespread assumptions of spiritual reality within a Pagan framework that consisted of deities and their influence in human affairs. We must not forget that while Christ-followers may have abandoned allegiances to their cherished deities, they would not have discarded the underlying pagan framework. In most cases, they would have incorporated Christ into it as we see in Ephesians, which describes powerful spiritual beings as evil forces intent on dominating people’s lives and influencing the world order. They were believed to be actual living creatures, not necessarily biological entities “of blood and flesh” (6:12), but just as real as humans or animals. Angels and demons may be apt examples of such beings, along with the devil, who is called “the ruler of the power of the air” (2:2). These spiritual beings were most likely the deities within the Pagan cosmological framework and as such were deemed as inferior rivals to Christ, who has been elevated to a position of dominance over them (1:20–21). Since Christ-followers share in Christ’s exaltation (1:22–23; 2:6; 3:10), they are equipped to withstand the struggle in “this present darkness” (6:12). The struggle against these entities extends to other Pauline writings, where they are called “elemental spirits of the universe” (Col 2:8, 20), “rulers” (Eph 1:21; 2:2; 3:10; 6:12; Col 1:16; 2:10, 15; cf. Rom 8:38; 1 Cor 15:24), “authorities” (Eph 1:21; 3:10; 6:12; Col 1:13, 16; 2:10, 15; cf. 1 Cor 15:24), powers (Eph 1:21; cf. Rom 8:38; 1 Cor 15:24), “dominions” (Eph 1:21; Col 1:16), and “thrones” (Col 1:16).

18.5.2 Elevation of the Church

Scholars have often pointed to the high ecclesiology in Ephesians. In many of Paul’s letters, the Greek term ekklēsia (“church”) often refers to a local congregation or assembly. However, in Ephesians it is not used this way. It is used, instead, to refer to “the universal church” (1:22; 3:10, 21; 5:2–25, 27, 29, 32). In Paul’s undisputed letters, Christ dies for sinners (Rom 5:6, 8), whereas in Ephesians Christ dies for the church (5:25), and as such it becomes unified and sanctified, without spot or blemish (5:25–26).

Ephesians is also distinct in its institutionalizing of the church on both the spiritual and earthly levels. As a spiritual institution, it is described metaphorically as the bride of Christ (5:31–32) and as a body of which Christ is the head (1:22–23; 4:12; 5:23; cf. Col 1:18)—which again differs from Paul’s undisputed letters (e.g. Rom 12:4–8; 1 Cor 12:12–27). As an earthly institution, the leadership of the church is organized into offices or positions such as apostles, prophets (2:20; 3:5; 4:11) evangelists, pastors, and teachers (4:11), all serving according to their gifts. The leadership equips the saints, who are the laity of the church, for ministry, edification, and growth for the purpose of achieving unity and maturity that is representative of Christ (4:12–13).

The appeal for the unification of the church, which suggests an underlying threat, is the main influence for all thirty-six ethical imperatives in 4:1–6:20. The expression “we are members of one another” (4:25) seems to be at the heart of each imperative that Christ-followers treat one another as extensions of themselves (5:28–30). The household is viewed as a pattern or microcosm of the universal church (2:19).

Info Box 18.3: The Christian Household Codes

Unlike the common household codes in Greco-Roman writings of the day which consisted of rules for the lower ranking members of a household, Eph 5:21–6:9 presents a table of household codes that are also directed at the more powerful members. For example, the directives are not only for wives, but also for husbands; not only for children, but also fathers; not only for slaves, but also for masters. Other examples of early Christian household codes are found in Col 3:18–4:1; 1 Tim 2:8–15; 5:1–2; 6:1–2; Titus 2:1–10; 1 Pet 2:13–3:7; 1 Clement 1:3; 21:6–9; Polycarp, To the Philippians 4:1–6:2.

18.5.3 Elevation of Believers

The author of Ephesians attributes an elevated status to believers. Since they are incorporated into the body of Christ, who was raised from the dead and exalted, they share in his elevated status (1:20; 2:6). The same power that raised Christ from the dead and exalted him is also available to those who believe (1:19–20) and can accomplish far more than any of them can possibly imagine (3:20). By this power, they can live in unity and holiness, and become what they were always destined to be—namely, creations of Jesus for good works (2:10).

Many interpreters argue that this theme is at odds with the undisputed letters where Paul objects to those who believe that they have been elevated to some special status in this life (see 1 Cor 4:8–13). It is also argued that Paul tends to identify Christ-follower with Jesus’ suffering and death rather than his resurrection and exaltation (Rom 6:3–5; 1 Cor 2:2; 15:31; Gal 2:19–20; Phil 3:10). This contrast has led to the proposal by some that Ephesians reflects the viewpoint of the “super-apostles” who Paul opposes in 2 Cor 11:5 and 12:11.

Those who argue that Ephesians was written by Paul offer a different explanation. In 2 Corinthians, Paul is correcting the notion that life in Christ is some sort of reprieve from service or suffering. In contrast to his opponents, Paul does not want believers to think that their new faith will be easy, or that their actions will have no consequences. In Ephesians, the context is different. Here, Paul wants to inform believers that they are no longer subject to spiritual powers, magical incantations, or curses that are invoked by their non-believing neighbours. Christ has freed them and exalted them above such powers.

Colossians

18.6 Introduction

While Colossians is very similar to Ephesians in its literary style and theology, it is less general, focusing more on specific false teaching that has confronted its recipients. The significance of Colossians has been widespread in the development of early Christian doctrine and theology. Its influence is particularly noticeable in the language of the Nicene Creed (325 CE), which has been recited by Christians in liturgical contexts for centuries (see below).

Colossians

“In him all things in heaven and on earth were created, things visible and invisible.” (1:16)

Through Christ “all things were made,” including “heaven and earth” and “all that is, seen and unseen.”

Christ is identified as “the image of the invisible God,” (1:15) and the one in whom “all the fullness of God was pleased to dwell.” (1:19)

Christ is “true God of true God” and “of one Being with the Father.”

Nicene Creed

Christ, who was before all things (1:17), took on a “fleshly body” (1:22) so that God could dwell in him “bodily” (2:9).

Christ “became incarnate” and “became truly human.”

Christ has been raised and “is seated at the right hand of God” (3:1).

Christ “rose again on the third day… ascended into heaven and is seated at the right hand of the Father.”

It affirms that Christ will be revealed “in glory” (3:4).

Christ “will come again in glory.”

In the first century, Colossae, which was located about 110 miles from Ephesus, was a relatively small city with limited influence in the Roman province of Asia, located in the western part of Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey). Apart from its mention at the beginning of the letter (1:2), there are no references to it in the New Testament. Along with its neighbouring cities, Laodicea and Hierapolis, it was known as a commercial center for textile production, particularly scarlet-dyed wool. All three cities, which were only a few miles apart from one another, consisted of the main urban centres in the Lychus River valley, but Colossae was in the shadows of Laodicea, which became the seat of Roman administration (Cicero, Letters to Atticus 5.21), and Hierapolis, which was celebrated for its healing thermal waters (Strabo, Geography 13.4.14). In approximately 61 CE, an earthquake devastated the region. While all three cities were eventually rebuilt, Colossae again appears to have been eclipsed by the importance of the other two and is seldom mentioned in literature from subsequent centuries.

There is good evidence that the churches in the three cities had close relations with each other. Paul mentions Epaphras who worked in all three of them (Col 4:12–13). He further asks that the letter to the Colossians be read in the church of the Laodiceans, and that the Colossians in turn read “the one from Laodicea” (2:1; 4:16).

Info Box 18:4: The Letter from Laodicea

What is the letter from Laodicea (4:16) that the Christ-followers in Colossae were supposed to read? A number of hypotheses about its authorship and content have been proposed. The common ones suggest that it was (1) a letter from Laodicea to Paul, (2) a letter from Epaphras to Laodicea, (3) an apocryphal letter of Paul to Laodicea, or (4) a letter from Paul to Laodicea, which could have resembled Philemon or Ephesians. The last option has received considerable traction. Since it is referred to as “the letter from Laodicea” it may indicate that it was initially sent to Ephesus with instructions for it to be passed on to Laodicea and then on to Colossae. This option fits Marcion’s claim that Ephesians was addressed “to the Laodiceans” (see 18.3 above). It is also supported by the early Christian writer Tertullian (d. 220).

Colossae and its neighbouring cities were known for their diverse Pagan cults, worship of astral deities (sun, moon, and stars), “mystery” religions, particularly those that involved the mother goddess Cybele, whose temple was centered in Hierapolis. Colossae also had a large Jewish population. Though Hellenized, it would explain why the author would identify Christ-followers as a new people who are “no longer Greek and Jew, circumcised and uncircumcised” (3:11).

Acts makes no specific mention of Paul ever going to Colossae, Hierapolis, or Laodicea, but during his second (16:6) and third (18:23) missionary journeys, Luke writes that Paul traveled through the region of Phrygia, which was a region that overlapped with the province of Asia. Luke makes no mention of Paul establishing churches in the region, which appears to correspond with “Paul’s” affirmation in Colossians that he had not met the recipients “face to face” (2:1). Instead the author recalls that they were taught the gospel by Epaphras (1:7–8).

18.7 Authorship and Dating

Like Ephesians, the authorship of Colossians has been disputed in contemporary scholarship. Those who uphold the traditional view that Paul wrote the letter point to the (self)-disclosure of Paul and Timothy as co-authors in 1:1, the standard Pauline structure, and important Pauline themes that are also found in the undisputed letters. Most scholars today, however, argue that there are good reasons for calling the traditional view into question. In particular, they point to difference in the letter’s writing style and theological concepts.

When Colossians is read in Greek, it is very apparent that the style is different from what is found in the undisputed letters. It contains much longer sentences that are stitched together by participles and relative pronouns, which are not always apparent in English translations that divide long sentences (e.g. 1:3–8; 2:8–15) into more manageable segments. While the undisputed letters also contain long sentences (e.g. Rom 1:1–7), they do not occur as frequently and are not constructed stylistically by using pleonastic synonyms (i.e. the use of more words than are necessary). The author of Colossians likes to stack words that convey the same idea (such as using “holy,” “blameless,” and “irreproachable” together in 1:22). By contrast, the undisputed letters contain many more succinct sentences with less repetition.

Colossians contains three main theological concepts that are developed in ways that differ from the undisputed letters. As a result, Colossians has often been viewed as containing a higher Christology, a broader ecclesiology, and a more “realized” eschatology. Since these are given considerable attention in the letter, they function as prominent themes, as discussed below in section 18.9.

The decision about the authorship of Colossians is dependent on how much latitude one is willing to grant Paul with regard to shifts in style and theology. Could Paul have developed or altered his style and theological thought later in life? The breadth of modern scholarly opinion can be categorized into three options: Paul; Paul’s immediate disciple; or a later follower of Paul.

1. Paul

Some scholars conclude that Colossians was indeed written by Paul. They note that there are stylistic differences between Colossians and the other letters of Paul, but they assume that these can be explained by Paul’s use of a secretary or amanuensis (see Modules 6.2.4 and 15.5.3). An amanuensis is someone who did not simply write verbatim what he heard, but instead had responsibility for crafting the letter as a literary composition. On this occasion, a scribe’s influence may have been weightier than normal. If Paul was in prison, his accessibility could have been restricted.

The theological developments in Colossians, noted above, are explained as a consequence of the unique context in which the letter was written. Since Paul was responding to the false philosophical ideas at Colossae, it is argued that his theological constructs would have been targeted.

If Paul wrote Colossians, then he likely wrote it near the end of his life, during his final imprisonment in Rome. Also, it would have had to be written prior to the earthquake of 61 CE, when Colossae was destroyed. Thus, 60 CE is commonly proposed.

2. Paul’s Disciple

The second option is that the letter was written by a close associate of Paul who was very familiar with his theology. Timothy has often been suggested as the best candidate since he was closely connected with Paul and his mission. Most likely, he would have continued in Paul’s program after his mentor’s death. In this scenario, the letter can be dated after Paul’s death, which could have been as late as 67 CE. It is also possible that the letter was written by Paul’s associate while he was still in prison. If Paul was not accessible or only had the opportunity to sign off on the letter after it was composed, then the letter might represent a blend of Paul’s thinking and that of his disciple. In this scenario, the letter could have been written in the early- or mid-60s CE.

3. Later Follower of Paul

A third option is that the letter was written well after Paul’s death by a follower who may not have known him, which would account for the diverse and developed theological concepts as well as the different writing style. If Colossians represents a later generation of followers, then its theological ideas would not necessarily represent those of Paul or his contemporaries. The writer may have thought that he represented Paul or, alternatively, the writer may have intentionally altered Paul’s ideas using his name. Even if the writer did misrepresent Paul, the use of his name would not constitute a fraud or deception as some have suggested. It is doubtful that Paul’s later followers would intentionally skew his message in order to deceive the recipients. Though they certainly could have developed Paul’s thinking in a way that was relevant to their situation. In the ancient world, pseudonymous authorship was common practice and can be viewed as a form of admiration and continuation of a teacher’s legacy. In this scenario, the letter is often dated in the 80s or 90s CE.

Opponents of this option point out that it seems strange for Paul’s disciples to choose the Colossian Christ-followers as the recipients of a pseudonymous letter since Paul was neither their founder nor a visitor. In response, it is argued that a later follower of Paul was influenced by his letter to Philemon, who most likely lived in Colossae. The two letters contain curious similarities.

Info Box 18.5: Did the Writer of Colossians Know Philemon?

There are curious similarities between Colossians and Philemon which may suggest influence. Both claim to be written from prison (Col 4:3, 18; cf. 1:24; Philem 9, 10, 13). Both ascribe authorship to Paul and Timothy (Col:1; Philem 1). And both letters mention the same individuals: Archippus (Col 4:17; Philem 2), Onesimus (Col 4:9; Philem 10), Epaphras (Col 1:7; 4:12–13; Philem 23), Mark (Col 4:10; Phil 24), Aristarchus (Col 4:10; Philem 24), Demas (Col 4:14; Philem 24), and Luke (Col 4:14; Philem 24). Not everything, however, corresponds. In Philemon, Epaphras is in prison with Paul, but Aristarchus is not (23–24), whereas in Colossians it appears to be the other way around (4:10, 12). Also, Colossians makes no mention of an impending visit from Paul, while Philemon indicates that Paul hopes to visit soon (22).

18.8 Purpose

The purpose of Colossians is clearly stated. It is a warning to a community of Christ-followers that they do not succumb to false teaching, which the author calls “philosophy and empty deceit according to human tradition” (2:4, 8). The exact nature of this false teaching is not explicitly made known in the letter. Only generalities are given, but the author seems to believe that the readers are aware of it and are familiar with it. The author counters this “philosophy and empty deceit” by indicating to the readers that they have already experienced a “spiritual circumcision” (2:11). Additionally, the author tells them that through Christ’s death, the requirements of the Jewish Law, which seem to concern food laws and the festivals, have been nullified (2:13–17).

The exact nature of this so-called “Colossian Heresy” has occupied scholars for a long time. Most likely, the false teachers are advocating a form of Judaism, perhaps even similar to the opponents Paul faced in Galatia. What makes these opponent different is that they also engage in “self-abasement and the worship of angels” and enter into visions which lead to conceit (2:18–19). These general references may indicate that the false teachers advocated an ascetic lifestyle and possibly the ecstatic adoration of higher beings. They were probably Jewish or Jewish Christian mystics who believed that ecstatic visions of heaven transported them from the present world to the divine realm where they experienced the power of divinity and ultimate joy. As ascetics, they would have denied their bodily desires in an attempt to experience the pleasures of a spiritual existence. Since they were Jewish, they likely urged their followers to keep kosher food laws, observe the Sabbath, and circumcision. The author associates the practices with human traditions and not God.

Info Box 18.6: Further Light on the “Colossian Heresy”

To date, there have been more than forty different proposals offered regarding the nature of the philosophy or “heresy” that Colossians confronts. Here are seven examples. (1) It was a Jewish Christian movement that insisted Gentile Christians must be circumcised and keep the law of Moses, similar to “the Judaizers” who opposed Paul in Galatians (see Gal 3:19; 4:3–9). (2) It was an esoteric and rigorous form of Judaism, comparable to the same one practiced by the Essenes at Qumran. (3) It was a mystical form of Judaism, like the merkabah tradition, which advocated asceticism, strict adherence to the law, and ecstatic experiences that were believed to be spiritual journeys to the heavenly throne room in a celestial chariot called a merkabah. (4) It was a syncretistic religious conglomerate of beliefs, combining elements from Jewish tradition with elements of astral religions. (5) It was some variety of a Greco-Roman “mystery religion” that emphasized the hidden nature of spiritual truth revealed only to the spiritually elite. (6) It was a nascent form of Gnosticism, a precursor of what would develop into prominent anti-materialist religious systems in the second century CE. And (7) it was Pythagorean philosophy based on the teaching of Pythagoras (sixth century BCE), who thought that the sun, moon, and stars were spirits that control human destiny, and that the human soul must be purified through ascetic practices (see Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers 8.24–33).

In response to these false teachers, the author of Colossians posits that Christ is the fullest expression of the divine, “the very image of the invisible God, and the firstborn of all creation” (1:15). The author argues that the worship of angels pales in comparison to the worship of the one “in whom all the fullness of God was pleased to dwell” (1:19). The main point throughout is to show the recipients that everything that is offered by the false teachers is already available in Christ as long as they do not depart from the gospel message they received (2:23).

18.9 Themes

18.9.1 Christology

In Colossian, the significance of Christ’s exaltation is developed beyond the undisputed letters. He is not only the ruler of the Church, but is also the ruler of the entire cosmos (1:15–17). He is not only the one who reconciles humanity, he reconciles all things in heaven and on earth (1:20). These reference to exaltation are part of the commonly called “Colossian Hymn” which may have been used in early Christian services as a confession and/or hymn (1:15-20). The author does not explain the points, nor does he defend them. He simply cites the liturgical material as though it was already accepted by the readers. The influence may have come from 1 Cor 8:6, which states that Christ is the one “through whom are all things, and through whom we exist.” If so, then the author expands on this conception by writing that Christ is the one “in whom all things in heaven and on earth were created” (1:16) and in whom “all things hold together” (1:17). Christ’s triumph and “public display” over the spiritual rulers and authorities in Col 2:15 may be an expansion of Paul’s assurance that no spiritual being or power will “be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ” (Rom 8:39). As well, it may be a realization of the promise in 1 Cor 15:24-25 that when the “end comes,” Christ will destroy “every ruler and every authority and power.” Finally, Colossians presents Christ as “the image of the invisible God” (1:15) and as the one in whom “the whole fullness of deity dwells bodily” (2:9), which may be a development of Paul’s reference to Christ as “being in the form of God” in Phil 2:6.

Info Box 18.7: Sophia and the “Colossian Hymn”

Presentations of Christ in the “Colossian Hymn” (Col 1:15–20) may have been influence by personifications of Sophia (translated as “Wisdom”) who functions as an agent of God in a category of Jewish literature that is today called Wisdom literature, such as Proverbs in the Old Testament, along with Sirach and the Wisdom of Solomon in the Old Testament Apocrypha. Note some interesting parallels:

Wisdom is “a spotless mirror of the working of God, and an image of his goodness” (Wisdom 7:26; cf. Col 1:15, 19).

Wisdom was “before all things” (Sirach 1:4; cf. Col 1:17).

Wisdom was present with God before creation (Prov 8:22–31; cf. Col 1:15).

Wisdom served as God’s agent through whom everything in heaven and earth was made (Prov 3:19; 8:27–31; Wisdom 7:22; 8:4–6; 9:2; cf. Col 1:16).

Wisdom “holds all things together” and “orders all things well” (Wisdom 1:7; 8:1; cf. Col 1:17).

Wisdom reconciles people to God, making them “friends of God” (Wisdom 7:14, 27; cf. Col 1:20).

While Wisdom literature presents Sophia in poetic language, we do not know how literally some readers would have taken it. Did some believe that Sophia was an actual divine being? Regardless, Jewish conceptions of Sophia appeared to have played a prominent role in understanding the relationship of Christ to both God and the world for early Christian groups in Asia Minor that were associated with Colossians, Ephesians and John’s Gospel.

18.9.2 Ecclesiology

The use of “church” in the undisputed Pauline letters usually refers to a local community of Christ followers (e.g. “the churches of Galatia,” “the church of God which is in Corinth”). On rare occasions, Paul may be implying a broader collective understand (Gal 1:13; 1 Cor 12:28; 15:9). While the local use of the term appears in the greetings at the end of Colossians (4:15–16), the primary reference is to a universal, even cosmic, collective body of Christ. As the ruler over the entire world, Christ is described metaphorically as the head of this body, which affects even the heavenly powers (1:18, 24). The influence may have come from 1 Cor 12:12–14, and 27, where Paul refers to believers as members of Christ’s risen body. While Paul uses parts of a physical body as an analogy, he never expands or develops this imagery in the way that the authors of Colossians and Ephesians do. Colossians implies that the church is the supreme accomplishment of Christ, and the end goal of Paul’s own work (1:24).

18.9.3 Eschatology

Colossians presents the status of believers in an exalted-like manner. The implication is that as Christ-followers, they are already experiencing a resurrected-like existence. This so-called “realized eschatology,” which appears in Ephesians and John, is strikingly different from a future eschatology characteristically found in the undisputed letters. In Colossians, believers are already in the kingdom of God’s beloved Son, have already “been raised with Christ” through baptism, and have been rescued from the power of darkness (2:12; cf. 3:1; (1:13), while in Romans believers have died and been buried with Christ through baptism and will someday be united with him in resurrection (6:4–6, 11). For some scholars, this difference alone seals the proposal that Colossians could not have been written by Paul.

However, caution is warranted since the symbolism associated with realized eschatology can be taken too literally and exclusively. Colossians still assumes a future eschatology, even if it is minimal. For example, in Col 3:4 the writer conceives of a final coming of Christ and a future glorification of believers. Regardless, scholars continue to discuss if being “raised with Christ” is a metaphor that is closer to or further from the conception in the undisputed letters that all believers have died in Christ and now live in him (before the resurrection of the faithful).

The claim that the Colossian believers have been raised already with Christ is likely meant in a spiritual sense. Believers still live on earth and should be concerned with proper behavior, despite the surrounding presence of dark powers and false teachings (3:18–4:1). A practical example in how present existence and spiritual reality are understood by the author is conveyed through the analogy of household codes (3:18–4:1), which address the relationship between slaves and their masters. As in Philemon, the attitude toward slavery here is ambiguous. On the one hand, slaves are instructed to obey their masters in everything as if they are serving Christ (3:22). On the other hand, masters are instructed to treat their slaves with fairness, reminding them of their “master in heaven” (4:1). The author speaks of the believers’ current status as hidden (3:3) and that it will be revealed when Christ returns (3:4). The aim is to provide the readers assurance that through faith they have entered into a new reality, albeit presently hidden, that will be revealed when Christ returns. As such they should live as free beings (3:1–3).

Info Box 18.8: Slavery in the Roman World

In addition to the discussion of slavery in Module 2.5, here is more contextual information that helps make sense of the language pertaining to slavery, masters, and freedom that the Prison Letters appropriate, often in a metaphorical way. The institution of slavery was deeply embedded in Roman society. Roman conquests often led to the enslavement of subdued groups. Individuals could be sentenced to slavery for various crimes. Entire families could be sold into slavery when someone defaulted on a debt. Since children who were born to slaves became the property of the master of the household, reproduction insured the sustainability and even growth of the slave population. During the first century, between one-third and one-fourth of the population living in the Roman Empire were slaves.

The life and conditions of slaves varied greatly. Social protocol encouraged humane treatment, and the extreme abuse or indiscriminate killing of slaves was prohibited by law. However, the welfare of the slaves relied greatly on the disposition of their masters. Slaves who worked in galleys or in the mines saw very harsh conditions that often led to death. Some slaves who belonged to benevolent householders would have even been education, and they would have enjoyed a lifestyle that would not have been possible as free persons. In fact, some willingly sold themselves into slavery in exchange for education or training in order to get employment. Slavery was not always permanent. In some cases, slaves were paid a wage and were allowed to purchase their own freedom after a period of time. In other cases, some slaves were automatically freed when they reached the age of thirty. Nevertheless, slaves had very few legal rights. They could be beaten at the discretion of their masters. They could not legally marry. They had no autonomy. And living in a society that valued honour and status, they were at the bottom of the social pyramid.

Philippians

18.10 Introduction

Among the undisputed letters, Philippians is one of the most affectionate. It has been classified as an example of the rhetoric of friendship. In addition to the warmth conveyed to the recipients, it contains one of the most affectionate and humble portrayals of Christ as one who emptied himself and took on the form of a servant, to the point of death on a cross (2:6–8). While Philippians is categorized as an undisputed letter, scholars debate its date, location, and its unity.

Philippi was a medium-sized Roman colony that was located in what is today northern Greece, about a hundred miles east of Thessalonica. Both cities belonged to the Roman province of Macedonia, of which Thessalonica was its capital. Since Philippi was located about ten miles from the port of Neapolis, which was one of the busiest ports in Macedonia, it enjoyed economic prosperity and a cosmopolitan social climate. Philippi was also a prominent resting point on the Via Egnatia, which was a Roman road that stretched from the Bosphorus Straight to the Adriatic Sea.

As a major Roman outpost that became something of a retirement community for Roman soldiers, Philippi was well known for its participation in the Imperial Cult, which was the practice of Emperor worship. In response to this practice, Paul emphasizes the worship of Christ as Lord (Phil 2:9-11), which would have raised eyebrows. Paul’s use of “Lord” (kurios) is very strategic because it was a common title for the Roman Emperor. Paul’s promotion of the Lordship of Christ could be viewed as subverting the grandeur and superiority of the Emperor. In effect, Paul could be saying that it is not the Emperor who rules, but it is Jesus as Lord, whose authority extends over the entire world and even over heaven.

Paul first came to Philippi with Silas and Timothy in 50–51 CE, where he founded his first church in Europe (Acts 16:11–15; Phil 4:15). According to Acts, Paul brought his gospel message to Europe in response to his vision of a Macedonian man imploring Paul to come to Philippi (Acts 16:6–10). At Philippi, Paul exorcised a spirit from a slave girl, which caused her owners, who had been benefiting financially form her abilities, to haul him and Silas before the local magistrates as troublesome Jews. It is no wonder that Paul described his time at Philippi as one of suffering and shameful treatment (1 Thess 2:2). Despite his treatment, when an earthquake jarred open the prison doors where Paul and Silas were being kept, they refused to escape. Their gesture led to the conversion of the jailer and his household.

Info Box 18.9: The “Dogs” and Other Opponents in Philippi

Philippians is not particularly polemical, but references to opponents do appear. Paul says that some proclaim Christ out of false motives such as envy, rivalry, and selfish ambition (1:15–18). These are likely Christian missionaries who cause factions and provide false teachings. There are also the notorious “dogs” who insist on “mutilating the flesh,” which is likely a reference to Jewish Christians insisting on circumcision (3:2). Then there are those who live as “enemies of the cross,” with their god as their belly, their glory in their shame, and their minds set on earthly things (3:18–19). These are likely references to those who seek power and glory while trying to avoid any suffering or service.

Paul’s converts in Philippi proved to be exceptionally loyal, as they supported him financially even when he ministered elsewhere (Phil 4:10; 16; 2 Cor 11:8–9). They even contributed to his collection for the Jerusalem famine relief effort (2 Cor 8:1–4; 9:1–5). At the end of the letter, he thanks them for yet another gift of support while he is in prison (4:10, 18).

18.11 Authorship, Place of Writing, and Date

The authorship of Philippians is rarely disputed. Paul identifies himself as the co-author, along with Timothy (Phil 1:1). The letter’s style, terminology, and theological concepts are consistent with the undisputed letters (see 18.12 below). When compared to the more heroic portrayals of Paul in Acts, the biographical data in Philippians is more subdued, suggesting authenticity.

Paul is undoubtedly writing from prison (1:7, 13–14, 17), but it is not clear from where or when. It is also not clear whether Philippians is the product of multiple letters that were stitched together. If so, then identifying their date and location becomes even more complicated.

Unlike the other prison letters, Philippians preserves details about Paul’s incarceration. These details are helpful for determining in which of the three imprisonments this letter was written, assuming it is not a pastiche of several letters. Although scholarship is still divided, consider the six details of Paul’s imprisonment that are recorded in Philippians:

While imprisoned, Paul was free to preach his message (Phil 1:7, 12-17)

Paul was awaiting a trial that would either lead to freedom or death (Phil 1:19-26, 4:18)

Paul was aware of the hostile preaching of his detractors (Phil 1:14-17)

Paul was with Timothy (Phil 1:1, 2:19-23)

Messengers were able to make several trips between Paul’s prison and Philippi (Phil 2:19-28, 4:18);

A praetorian (Imperial) guard and members of Caesar’s household were nearby (Phil 1:13).

With these six details in mind, let’s take a closer look at the three imprisonment that are often proposed as the location for the writing of the letter.

18.11.1 Rome Imprisonment (60–63 CE)

Rome has been the traditional option for several reasons. First, beginning in the second century, Christian scholars collectively assumed that Paul was imprisoned in Rome when he dictated the letter. Second, Acts records that Paul was under “house arrest” (Acts 26:16-31) while awaiting trial in Rome. Being under house arrest would have allowed Paul to write letters, receive visitors, and freely proclaim his message. And third, the presence of members of the Praetorian Guard and Caesar’s household suggest Rome, but they were not exclusive to Rome.

This location, however, is not without its challenges. Rome is 700-1200 miles away from Philippi (depending on which form of transportation is used), making it difficult to conceive of “messengers” making several trips. If the average distance covered by travelers in antiquity was no more than 20 miles per day, assuming a day of rest per week, it would take at least two and a half months to travel one-way. If Paul’s imprisonment lasted nearly two years, it is difficult to account for more than one visit.

18.11.2 Caesarea Maritima Imprisonment (57–60 CE)

Less popular is the suggestion that Philippians was written during Paul’s imprisonment at Caesarea Maritima, which was a port city in Palestine, named in honour of Caesar Augustus. According to Acts, the imprisonment at Caesarea Maritima allowed Paul the same freedoms that he experienced in Rome. He was free to preach his message and to receive guests (Acts 24:23). Acts also records that Paul was held at the headquarters of Herod (23:35), where one would have likely encountered members of the Praetorian Guard and maybe even members of Caesar’s household.

This option also faces challenges. First, Caesarea Maritima is further away from Philippi than Rome (nearly 1400 miles), suggesting all the more that it would have been virtually impossible for “messengers” to travel from Philippi to Caesarea Maritima multiple times during a two-year imprisonment. And second, Paul was not in danger of being executed in Caesarea Maritima. Despite his accusations by Jewish authorities, he had the option to appeal to Caesar (see Acts 25:7-11). A trial leading to a potential death sentence was simply not in the cards at that point, which does not correspond with the attestation in Philippians.

18.11.3 Ephesus Imprisonment (52–58 CE)

Many scholars today opt for Ephesus as the probable location for the composition of Philippians. Once again, the corresponding material in Acts serves as a point of reference. We read in Acts, for example, that Timothy was with Paul in Ephesus (19:22, 20:4). Most conclusively, though, Ephesus is located much closer to Philippi than any of the other options (about 675 miles), which could foreseeably account for “several” visits by the “messengers.”

The major challenge that stands in the way of this option is the lack of evidence that Paul was an actual prisoner in Ephesus. Acts is inconclusive (19:23-40). There are two references to Paul’s suffering in Ephesus in the Corinthian letters (1 Cor 15:32; 2 Cor 2:8-10), but they do not mention an imprisonment. Like Caesarea Maritima, Paul did not face death at Ephesus given his Roman citizenship and right to appeal to the Roman judicial system. Lastly, it is unlikely that members of the Praetorian Guard or Caesar’s household were stationed in Ephesus. It is more likely that these high-ranking government officials would have been located at nearby Pergamum, not Ephesus.

In the end, scholars have not reached a consensus on the date and location of the letter, which has been frustrating for those who want to put Paul’s letters into a chronological sequence in order to track the development of his thoughts. If Philippians was written from Paul’s imprisonment in Ephesus, as is the common view, then it is one of Paul’s earliest letters. However, if it was written from Rome, then it is one of his latest.

Info Box 18.10: Imprisonment in Paul’s Day

The purpose of imprisonment in the Roman world was neither to reform prisoners nor to simply punish them. It simply served as a means of confinement while awaiting trial. Once a verdict was rendered, the sentence could be carried out. Most prison cells were basically dungeons. They were dark and isolating. Not all incarcerations were located in cells, however. Sometimes respected individuals could be held under a form of “house arrest,” where they would be guarded by soldiers and allowed a relative measure of comfort and freedom. According to Acts, Paul experienced both the best (28:16, 30–31) and the worst (16:23–24) of these possible forms of captivity at different points in his career (cf. 2 Cor. 11:23). There is much debate about what type of imprisonment Paul is experiencing when writing Philippians. Paul says that he is “in chains,” despite the translation of the Greek word desmos as “imprisonment” in some Bibles (1:7, 13, 14, 17). If Paul is being literal, then he is likely experiencing the worst form of captivity. If he is being metaphorical, then he is in less grueling conditions. The latter may be the case since he is able to converse with his colleagues, receive gifts, and dictate the letter.

18.12 Audience

Paul’s target audience was likely Gentile converts. Acts records that Paul found these converts praying “outside the city near a river” (Acts 16:13), suggesting that they were not Jewish as they would have prayed in a synagogue setting. In fact, there is little evidence to suggests that there was a Jewish presence in the city prior to Paul’s ministry. The so-called “mutilators of the flesh” were likely Jewish Christian missionaries who arrived in Philippi after Paul. Apart from ethnicity, the Christ-followers in Philippi are appreciated for their kindness and generosity. Elsewhere, Paul likewise praises the Philippians for their rich generosity that arose out of their “extreme poverty” (2 Cor 8:1-5, 11:9).

18.13 Purpose: One Letter or More?

The specific circumstances the led to the composition of the letter are not easy to determine. One of the main reasons for this is that Philippians may have been composed from several shorter letters, which probably had different aims.

That Philippians is a pastiche of prior letters is not a modern proposal, but goes back to Polycarp, the second-century bishop of Smyrna who mentions that Paul wrote letters to the Philippians. His use of the plural continues to raise questions about the letter’s compositional history. Modern scholars also point to internal features that imply added sections. Consider the following:

Phil 3:1a; 4:8–9; and 4:21–23 each sound like possible conclusions to a letter.

Phil 3:1b–4:3 consists of warnings against enemies in contrast to the rest of the letter which conveys a happy tone.

Phil 3:1b (“to write the same things to you is no trouble for me”) suggests previous correspondence.

Phil 3:1a begins with “Finally,” which suggests a close, but it appears in the middle of the letter.

Phil 2:23–30 mentions travel plans, which usually appear at the end of Paul’s letters.

Phil 4:10–20 expresses thanksgiving for a gift, which typically appears at the beginning of a letter rather than at the end.

Phil 2:25–30 conveys that Paul will send Epaphroditus to Philippi, but Phil 4:18 assumes that Epaphroditus had returned from Philippi back to Paul.

These observations have led scholars—who hold that Philippians is constructed from several letters by a later editor—to generally adopt one of two possibilities. The first is that it is composed of two letters. The first letter would have been written when Paul received the gift delivered by Epaphroditus (3:1b–4:20) and the second letter would have been written after Epaphroditus recovered from illness (1:1–3:1a; 4:21–23). The second reconstruction, which is more common, proposes three letters. The first letter would have consisted of acknowledgment and gratitude for the gift received by Paul from the Philippians (4:10–20). The second letter would have encouraged hope and confidence in a worthy life based on Christ (1:1–3:1a; 4:4–7, 21–23). And the last letter, which was polemical, would have addressed the problems in the church (3:1b–4:3; 4:8–9).

Scholars who support one of these reconstructions think that Philippians makes better sense when its contents are reorganized into two or three different compositions. Other scholars, however, are not convinced and find such theories to be unnecessary imposition, arguing instead that Paul dictated the letter over a period of time, which would explain the abrupt shifts in content.

The letter in its current form best suits the genre of a “friendship letter.” As such, Paul’s main purpose would have been to update his friends and ministry partners on his current situation (1:12–26), to ease their concerns about Epaphroditus (2:25–30), and to thank them for their gifts (4:10–20). While he also addresses concerns about his recent imprisonment and the challenges in Philippi, most scholars still think that the primary focus of the letter is on cementing and celebrating Paul’s relationship with his fellow Christ-followers.

18.14 Themes

18.14.1 The Person of Jesus Christ

Unlike the portraits of Christ that are presented in both Ephesians and Colossians, which present the significance of Christ’s exalted status as Lord over the church and the cosmos, Philippians focusses on the person of Jesus Christ, emphasizing his “earthly” state. Paul’s portrayal is preserved in what scholars call a “hymn” or “poetic” representation in Phil 2:6-11. This so-called “Christ Hymn” was probably recited in Christian worship gatherings as a creed or responsive reading or maybe even as an actual hymn that was put to music and sung or chanted. It is uncertain whether Paul composed it in part as a whole. If he inherited it (or part of it), then it represents the oldest Christian liturgical material that we have.

The hymn celebrates Christ’s life and death by relying on allusions from the Old Testament. The voluntary humiliation of Christ in the first part draws upon the Suffering Servant in Isa 52:13–53:12, and the universal submission to Christ at the end of the hymn borrows from the reference to God’s sovereignty in Isa 45:23. Also, Christ’s willingness to give up his “equality with God” can be viewed as a contrast to Adam’s desire to attain equality with God in Gen 3:1–7. Paul explains that the humility of Jesus, which led to the cross, resulted in his exaltation. Surpassing even the honour of the Emperor, he is given a status that requires every person in the world to bow before him and confess that he is the Lord of the world (Phil 2:9-11). The principle of greatness achieved through humility functions on a practical level in the Philippians’ pursuit of sanctification.

Info Box 18.11: Earliest Christian Hymns

While there is scattered mention of hymns and spiritual songs in the New Testament (Acts 16:25; 1 Cor 14:15, 26; Col 3:16; Eph 5:19; Heb 2:12; Jas 5:13), the earliest Christians did not have a common songbook or hymnal comparable to the book of Psalms. Instead, they are references to brief liturgical material that is woven into the writings. Notable examples are found in the Gospel of Luke (1:46–55, 67–79; 2:14, 29–32) and Revelation (1:5–6; 4:8, 11; 5:9–14; 7:10–12, 15–17; 11:15–18; 12:10–12; 15:3–4; 16:5–7; 19:1–8; 22:13). Some of the letters attributed to Paul also appear to draw upon hymns or songs that were probably recited orally during worship gatherings. Some often-cited examples include Rom 11:33–36 (doxology on the mystery of God), 1 Corinthians 13 (superiority of love), Phil 2:6–11 (doxology on the self-abasement and the ensuing exaltation of Christ), Col 1:15–20 (glorification of Christ), Eph 1:3–14 (doxology on the redemptive work of God in Christ), Eph 5:14 (promise of the life and light of Christ), 1 Tim 3:16 (the return of Christ), and 2 Tim 2:11–13 (suffering for Christ leads to glory). One of our earliest references to collective Christian recitations comes from a Roman source. Around 110 CE, a Roman governor named Pliny the Younger wrote a letter to Emperor Trajan in which he described Christian gatherings that included the practice of chanting “verses alternately amongst themselves in honor of Christ as if to a God” (Letter to Trajan 10.96). The “Christ Hymn” in Phil 2:6–11 serves as a perfect example of this sort of material that was recited on a regular basis.

18.14.2 Pursuing Sanctification with Humility

Paul encourages the Philippian Christ-followers to seek a state of sanctification, which is patterned after the humility of Christ. He uses his own experience as part of the encouragement. After recalling his many accomplishments and “perfections” in the eyes of the Jews (Phil 3:3-6), Paul reduces them to “rubbish” when compared to “the surpassing value of knowing Christ Jesus my Lord” (Phil 3:8). Coming to a knowledge of Christ, which is far more than a cognitive process, comes at high price. One must “suffer the loss of all things” (Phil 3:8) to properly prepare for the way forward in pursuit of sanctification. While he uses his own experiences, Paul confesses that he has not yet achieved the goal, but continues to press on (Phil 3:12–13). The goal is also the reward, namely “the heavenly call of God in Christ Jesus” (Philippians 3:14), which may refer to a heavenly entrance based on the deeds and behavior that mirror those of Christ.

Paul does not leave the Philippians with generalities. He counsels them to not only think about those things which are true, honorable, just, pure, pleasing, commendable, excellent, and praiseworthy (4:8), but to act on them as well. For these virtues will ultimately purify the Christ-followers and allow them the ability to receive the peace of God, which is the manifestation of a pure life.

18.14.3 Joy in Suffering

Paul attempts to empathize with the Philippians, who are experiencing persecution from other Christ-followers, by appealing to his imprisonment. He writes, “others proclaim Christ out of selfish ambition, not sincerely but intending to increase my suffering in my imprisonment. What does it matter? Just this, that Christ is proclaimed in every way, whether out of false motives or true; and in that I rejoice, Yes, I will continue to rejoice, for I know that through your prayers and the help of the Spirit of Jesus Christ this will turn out for my deliverance” (1:17-19).

Since suffering and persecution due to one’s commitment to Christ is not meaningless, but is a sign of faithfulness and assurance of reward in the afterlife, Paul encourages the Philippians not to be intimidated, but to see it as a means to their salvation (1:28). For just as Christ suffered, and Paul currently suffers, the Philippians are to count it as joy. But suffering should not be seen as an individual experience that leads to the sanctification of the sufferer. Rather, it should be seen as a collective act that edifies and encourages the entire community to remain faithful and to pursue purity (2:4).

Philemon

18.15 Introduction

The letter to Philemon, which contains only 335 words (in Greek), is Paul’s shortest in the New Testament. However, by Greco-Roman standards of letter writing, it would have been an average length. It is also the only undisputed Pauline letter written to an individual. Its content is likewise distinctive since it addresses the relationship between a Roman master, named Philemon, and his runaway slave, Onesimus. Since the letter provides insight into the issue of Roman slavery in relation to Paul’s faith, it has generated considerable attention. The main issue for modern readers is that Paul does not condemn slavery.

18.16 Authorship

Paul’s authorship of Philemon has rarely been questioned. At the beginning of the letter, he is identified, alongside Timothy, as the author (1:1). His authorship is reiterated in 1:19 where he acknowledges that he writes “with his own hand.” Historically, Paul’s authorship was unanimously accepted by well-known figures, such as Marcion, Origen, Jerome, John Chrysostom and Theodore of Mopsuestia.

Info Box 18.12: Paul’s Creative Use of Language

In Philemon, we find Paul choosing his words in a creative manner, sometimes in a witty way. Scholars have observed three forms. First, he uses a wordplay when he refers to Onesimus as “my own heart” (v. 12) and then calls on Philemon to “refresh my heart” (v. 20), which conveys a double meaning. Second, he uses “paradoxical tact” when he says that he is not going to mention the debt that Philemon owes him (v. 19), but of course, in so doing, he mentions it. And third, Paul uses a pun when referring to Onesimus as once being “useless,” but is now truly “useful” (v. 11). The word “useless” (achrēstos) is similar to a word that means “without Christ” (achristos). The word “useful” furthermore is a pun on Onesimus’ name, since onēsimos literally means “useful.”

18.17 Place of Writing and Date

While Paul is clearly writing from prison, we are again left with the problem of identifying the location and the date. There are not many clues in this brief letter, apart from Paul anticipating his pending release, after which he plans to stay with Philemon (v. 22). Consider the same three options.

18.17.1 Rome Imprisonment (60-63 CE)

Like the location of the other Prison Letters, Rome has served as the traditional proposal. The only potential evidence for this view from the letter itself is Paul’s mention that he is “an old man” (v. 9), which would likely not be used during earlier periods of his travels. For most scholars today, however, Rome is an unlikely option for at least three reasons. First, the distance between Rome and Colossae, from where Onesimus ran away, is prohibitive. Onesimus’ travels from Colossae to Rome, where he met Paul, along with Paul’s request that he travel back would have been too risky for a runaway slave. While an urban centre like Rome could have provided a good cover, the journey back to Philemon’s estate would have left Onesimus exposed to opportunistic travelers who would have looked to collect a ransom for a runaway slave. Second, there is no in evidence in Acts that Paul anticipated imminent release from his incarceration in Rome. And third, if Philemon was from Colossae, the Rome imprisonment is problematic because it overlaps with the earthquake which destroyed most of Colossae. Why would Paul send him back to a destroyed city, assuming he knew about it?

18.17.2 Caesarea Maritima Imprisonment (57-60 CE)

The imprisonment in Caesarea Maritima is also an unlikely option. While Paul could still have categorized himself as “an old man” and could have anticipated an imminent release on the grounds of his citizenship, the distance is again problematic. Like Rome, Caesarea Maritima may have provided a place for Onesimus to hide, but its distance would have elevated the risk of capture during the long journey. Few scholars hold to this position today.

18.17.3 Ephesus Imprisonment (52-58 CE)

The imprisonment in Ephesus may be the best option for at least two reasons. First, Colossae is located only about 100 miles from Ephesus, making the distance covered by a runaway slave more manageable with considerable less risk of being caught. Second, the proximity of Colossae would account for Paul’s request to stay at Philemon’s home after his release (v. 22). The only wrinkle in this option is again that there is no explicit mention of Paul being in prison in Ephesus. He certainly could have, given the trouble he experienced there, but it remains inconclusive.

18.18 Audience