Module Four

Religious Background: Judaism

4.1 Introduction

First century CE Judaism was a rich and vibrant religious environment within which Jesus, his disciples, and most of the New Testament writers lived. While there are several similarities between early Christianity and the Greco-Roman religions and philosophies, none was as influential as Judaism; it was the cradle of early Christianity. Before Judaism and Christianity parted ways, after the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE, Christianity was essentially a Jewish sect or party. The term “sect” is here used to refer to any minor religious group or movement within the confines of Judaism.

Fig. 4.1: Devout Jew praying at the Western Wall (or “Wailing Wall”), which is today one of the most sacred sites in Judaism.

Like most religions in late antiquity, Judaism was inseparable from politics and society in general. The Temple in Jerusalem, for example, was not only a place of worship, but it functioned as the national treasury. Unlike the other religions, however, Judaism was ethnic – meaning that most of its devotees were born into it. As such, it was a national religion that had its own forms of social, political, and religious hierarchy and institutions that were rooted in the biblical legal tradition, despite being under the control of Rome. In Palestine, where most Jews lived, the hierarchical system was rooted in the Jerusalem Temple and the Sanhedrin, the highest Jewish legal assembly. By the first century CE, Jewish people were scattered throughout the empire. Those living outside of Palestine are known as Diaspora or dispersion Jews. Particularly sizable communities were found in Alexandria and Rome.

Fig. 4.2: Depiction of Philo of Alexandria, Düssoldorf, 1584.

Diaspora Jews were influenced by the cosmopolitan nature of Roman society. Scholars today speak of Hellenistic Jews or Hellenistic Judaism, which refers to Jews who were influenced by (and integrated into) the mainstream Greco-Roman culture. Philo, a first century Jewish philosopher from Alexandria, is a good example of a Hellenistic Jew of the Diaspora. He essentially married Greek philosophical traditions with the Jewish scriptures. Often dubbed as the father of allegory, his interpretations resulted in a Jewish version of Greek philosophy.

Some gentiles were attracted to Judaism. Those that converted fully were called proselytes, and those that followed Jewish teachings, but did not undergo circumcision, were called God-fearers. Both proselytes and God-fearers must have considered Jewish monotheism superior to pagan polytheism and superstition. Though, some may have simply incorporated the Jewish God into their personal pantheon. Converts may have also been attracted to Jewish community life, its views on morality, promise of immortality, and the considerable age of the Jewish religion, which would have been particularly attractive to Romans.

Fig. 4.3: God-fearer inscription from the theatre at Miletus, Turkey. The theatre was completed in 133 BCE. The inscription designates the occupants of the seat, It reads, “The place of the Jews who are also called God-worshipers.”

4.2 Jewish Groups

Fig. 4.4: Detail of the mosaic of the Battle of Issus, National Archaeological Museum, Naples, 1st century BCE.

In Palestine, first-century Judaism was not a uniform or homogeneous religion. It was practiced by a variety of groups that differed in their beliefs, rituals, and interpretations. Many of these groups emerged during the Hellenistic period (from the time of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE to the Maccabean Revolt in 142 BCE). Though there seems to have been tolerance between groups in general, each group appealed to the scriptures to justify its own identity and superiority over rival Jewish groups. The scriptures were the main source from which traditions were developed, motifs were typologized, laws were amplified and reapplied, non-historical texts were historicized, and prophecies were deciphered, reapplied, or revitalized. This period produced some radical interpretive methods that led to innovative results. The Jewish historian Josephus, for example, lists four main Jewish groups in the first century: the Pharisees, the Sadducees, the Essenes, and the Fourth Philosophy. Modern historians have also included the Samaritans and the early Christians to this list. Because of their prominence in the New Testament, the Pharisees and Sadducees are here treated in more detail than the other groups.

4.2.1 Pharisees

Fig. 4.5: Duccio di Buoninsegna, “Christ Accused by the Pharisees,” Museo dell’ Opera del Duomo, Florence, c. 1311.

Since the Pharisees appear in the New Testament as a prominent group, their identity and role in first century Palestine have preoccupied scholars for over a century. Pharisees have been described in a number of ways, such as a leading political group, an influential religious party, an academic group, and a lay movement seeking the priesthood. The reason why there have been various descriptions is that ancient texts referring to the Pharisees are fragmentary and biased. Our main sources for understanding the Pharisees are (1) the gospels, which tend to paint them in a negative light, (2) Josephus, who tends to portray them positively, perhaps because he himself claimed to live his public life as a Pharisee, and (3) later rabbinic writings, which were written by the successors of the Pharisees from the second century onward. In the past, apologetically minded Jewish and Christian scholars used these sources to defend the historical reliability of the gospels on the one hand or Josephus and the rabbinic writings on the other.

History

Fig. 4.6: Prutah minted under the reign of John (Yehohanan) Hyrcanus I “Yehohanan the High Priest and the Council of the Jews.” 130-104 BCE.

The history of the term “Pharisee” is unclear. Most scholars think that the term originally meant “the separate ones,” as derived from the Hebrew and Aramaic root meaning “to separate.” The term “Pharisee” first appears during the reign of John Hyrcanus (154-134 BCE), who was high priest and ruler of the Jews during the Hasmonean period. Josephus records that John Hyrcanus was at first a disciple of the Pharisees, but eventually switched his allegiance to their rivals, the Sadducees (Ant. 13 §§288-296). It is commonly argued that the Pharisees were the successors of the Hasidim or Hasideans (“the pious ones”), a group that arose in support of the Maccabean uprising against the Hellenizing policies of the Seleucids. Throughout their existence, the Pharisees served as advisors to some Jewish rulers, but during the reign of Herod their opposition to the Romans quashed any chances of resuming high-level advisory posts.

The Pharisees of the first century CE can be described as a literate and organized group that sought influence with the ruling class in order to achieve their ideals of how society was to function. They are best situated within the retainer class, which was subordinate to and dependent upon the ruling class. Individual Pharisees, however, became important leaders due to their prominence within the group or on the basis of family status. On the whole, they were well known for their social concerns and respected for their extra-biblical traditions and interpretative abilities, perhaps because these traditions were already popular. Many of them served as religious and legal teachers, bureaucrats, and magistrates. Josephus tells us that during the first century there were approximately 6000 Pharisees in Palestine (Ant. 17 §42).

Josephus

Fig. 4.7: Old Jewish cemetery, Prague, 15th century. Pharisaic belief in the resurrection was endorsed by subsequent rabbis and continues to be part of Jewish liturgy.

Although there are about fourteen different passages in the works of Josephus that mention the Pharisees, two are particularly relevant and most often considered as background material for the New Testament, partly because they are set within the same historical period, namely the Herodian era and the war with Rome. In the first account (War 2.8.14 §§162-63, 166; cf. Ant. 13.5.9 §172), the Pharisees are described as having the reputation of being the most accurate interpreters of the laws. They are further described as believing in fate and the post-mortem re-embodiment of the souls of righteous persons. Their relationship with one another and with the community is marked by affection and harmony, in contrast to the Sadducees, who Josephus claims are rude to one another and to outsiders.

In the second account (Ant. 18.1.3 §§12-15), which is written approximately fifteen years later (93-94 CE), the Pharisees are presented as influential among the townsfolk, who try to emulate the Pharisees’ beliefs and character. The beliefs described in this passage are similar to the previous passage. They include the post-mortem re-embodiment of the soul, punishment for evil souls and reward for good souls, and the combination of fate and free will. Their character is marked by integrity and tolerance as displayed through their simple lifestyle, faithful observation of their own commandments, and respect and deference for their elders. Josephus describes the Pharisees as being so popular and influential that “all prayers and sacred rites of divine worship are performed according to their exposition.” Josephus also extends his report of their influence to the political realm by describing their opposition to the revolutionaries who captured the fortress of Masada (War 2.17.3 §411).

Fig. 4.8: The Masada Fortress with the Dead Sea in the background.

We must consider these sources cautiously, however, since they may well express Josephus’ personal bias as a former Pharisee and underlying intentions to satisfy his Roman patrons.

Rabbinic Literature

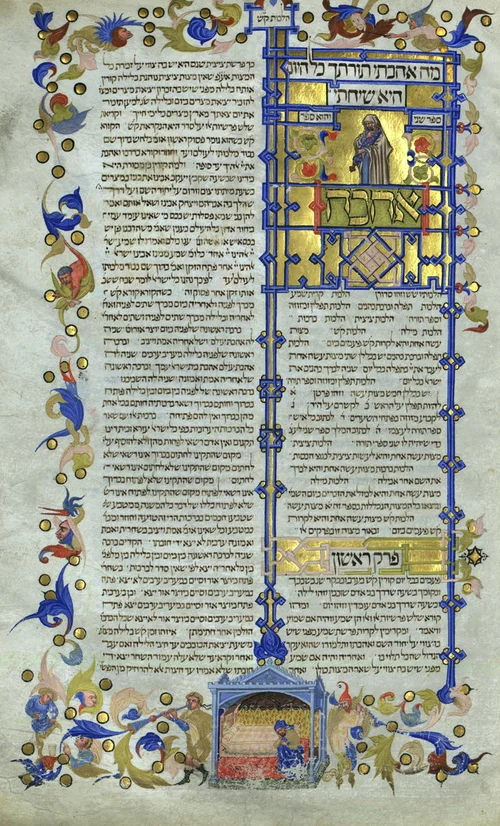

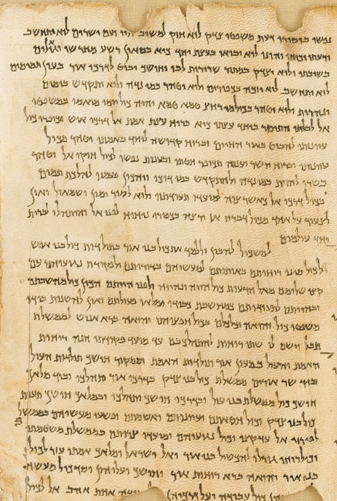

Fig. 4.9: Page from a 14th-century Spanish Mishnah manuscript.

Rabbinic writings, such as the Mishnah (which was a compilation of Jewish oral laws) and the Tosefta (a commentary on the Mishnah), post-date the New Testament. Since these writings contain sporadic references to the Pharisees, they have been used as a source by some New Testament scholars. Caution, however, is strongly recommended when using these sources for reconstructing pre-70 CE Pharisaism. Not only were these writings written well after the Pharisaic movement ceased to exist, they were written by the successors of the Pharisees, called “the rabbis,” who advocated a pro-Pharisee and anti-Sadducee bias.

The focus within the sketchy rabbinic accounts concerning the Pharisees is on the internal affairs of the group, with primary interest given to the relationship between the House of Shammai and the House of Hillel, which were two schools of thought within Pharisaism. Much of the debate within the party, according to rabbinic material, centers upon ritual purity, agricultural taboos, Sabbath and festival behavior, and how these practices affect table-fellowship.

The New Testament

Overall, the numerous references to the Pharisees in the gospels do not include much detailed information about their role and beliefs, despite their interactions with Jesus on a host of topics, such as ritual purity, the Sabbath, marriage and divorce, and religious and political authority. That the historical Jesus had dealings with the Pharisees should not be doubted. Since Jesus was not a prominent figure during his lifetime, he would not have been noticed by the ruling class of Jerusalem, but he would have been confronted by local leaders, like the Pharisees, who were also vying for influence among the common people.

Fig. 4.10: Detail of Michelangelo’s “Pieta Bandini” depicting the Pharisee Nicodemus (as a self-portrait) holding the body of Christ. Museo dell’ Opera del Duomo, Florence, 1555.

For historians, one of the problems with using the gospel accounts is that the Pharisees are often portrayed in a negative light as the antagonists and inquisitors of Jesus. The bias of the evangelists is particularly noticeable when the Pharisees – many of whom were well educated – are portrayed as being rhetorically and intellectually inferior to Jesus. They often lack a response to his questions. Their portrayal in the gospels does not coincide with our information about them in Josephus and the rabbinic literature where they are described as experts in the law and Jewish traditions. The different portrayals do not necessarily invalidate the historicity of the conflict accounts in the gospels, but the details themselves need to be considered with caution and awareness of the intention and bias of each author.

In several gospel passages, scribes are placed alongside the Pharisees (e.g. Matt 12:38). Scribes were professionals who could read and write and were well known for their ability to interpret the law. They served as secretaries and chroniclers, taught the scriptures in synagogues, and adjudicated legal disagreements in court. Because of their strict devotion to the scriptures and their role as custodians of Jewish tradition, many of the scribes were Pharisees, but not all Pharisees were scribes. The designations “lawyer,” “scribe” and “teacher” were essentially synonymous.

4.2.2 Sadducees

In comparison to the Pharisees, the Sadducees have received very little attention by historians. Most historical descriptions of the Sadducees come from Josephus, the New Testament, and rabbinic literature. However, a reconstruction of this group based solely on these sources is of limited value. The problem is that all of these sources represent an antagonistic perspective toward the Sadducees. In other words, they were written by individuals or groups that were hostile to the Sadducees.

History

The derivation of the name “Sadducee” is difficult to establish and has generated at least two possibilities. Some scholars suggest that the name derived from the Hebrew root word for “righteous” or “just.” Others have connected the name with Zadok, who was high priest during the reign of David (2 Sam 8.17) and Solomon (1 Kgs 1.34).

Fig. 4.11: Prayer shawls like this one were commonly worn by Sadducees who were priests.

Like the Pharisees, the Sadducees emerged during the Hasmonean period. They began as supporters of the expansionist policies of the Hasmonean princes and soon wielded political influence and authority. During the time of Jesus, the Sadducees were a small group numerically, but exercised widespread control among Jews in Palestine. They controlled both the Temple and the Sanhedrin, and maintained practical relationships with Roman governors. Many of the Sadducees were landowners and could be classified as belonging to the elite class. Recent research indicates that several of Jesus’ parables may have been directed at the Sadducean landowners. After the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE, the Sadducean aristocracy disappears from history.

Josephus

When Josephus’ portrayal of the Pharisees is compared with the Sadducees, a stark contrast is immediately observed. The Sadducees appear to have no redeeming qualities or beliefs. Although Josephus does not mention the Sadducess as often as he does the Pharisees or the Essenes, he does include three references that may be helpful for understanding this group.

First, in War 2.8.14 §§164-66, Josephus contrasts certain beliefs and behavioral qualities of the Sadducees with those of the Pharisees. In the context of describing the Jewish philosophical schools, the Sadducees (called the second school) are described as rejecting fate and endorsing free will. The implication is that God is in no way responsible for evil. Also, unlike the Pharisees, they deny the immortality of the soul. As mentioned above, they are identified as being ignorant among themselves and rude in their interactions with their peers from other sects.

Fig. 4.12: Russian Orthodox icon of James, the brother of Jesus. Unknown artist, 1809.

Secondly, a similar contrast of certain beliefs is recorded in Antiquities 18.1.4 §16-17 (cf. 13.5.9 §171-72). After describing certain Pharisaic beliefs and practices that win favor among the townspeople, Josephus launches into a brief description of the Sadducees’ beliefs and practices that, by vivid contrast, appear inferior. Unlike the Pharisees, the Sadducees are described as (1) believing in the more traditional view of the mortality of the soul and body, (2) accepting no observances apart from the written laws, and (3) encouraging disputes with their teachers. Josephus closes by claiming that when the Sadducees assume high offices, they submit unwillingly to “the formulas of the Pharisees” due to public pressure.

Finally, in Antiquities 20.9.1 §199, Josephus describes how Ananus the Sadducean high priest had James, the brother of Jesus, along with several others, executed just prior to the war with Rome. This is the only place where a high priest is described as a Sadducee. A brief general statement describes the Sadducees as being “more heartless than any of the other Jews... when they sit in judgment.”

Rabbinic Literature

Fig. 4.13: Carl Schleicher’s “Eine Streitfrage aus dem Talmud,” depicting a stereotypical debate among rabbis over the Torah and rabbinic tradition. Dorotheum Gallery, Vienna, c. 1866.

In the rabbinic writings there are relatively few appearances of the Sadducees. When they are mentioned, it is usually in contexts where they disagree with the Pharisees or sages. Since the Sadducees are usually painted in a poor light for not conforming to the traditions of the Pharisees, the historical reliability of the rabbinic literature as it looks back on the first century is considered suspect. The negative portrayal of the Sadducees is used to defend the legitimacy of rabbinic teachings. In later rabbinic writings, like the Talmud, they are sometimes even considered heretics or illegitimate Jews. The Sadducees become stereotyped as the adversaries of the Pharisees. Unfortunately, they are not portrayed as an authentic first century group with its own identity and interpretation of Judaism.

The New Testament

The portrayal of the Sadducees in the New Testament is consistent with Josephus and rabbinic literature on at least two points: their denial of resurrection, and the group’s elite status in Judaism. The denial of resurrection is of particular interest for obvious reasons. In the synoptic gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke), the only appearance of the Sadducees in which another group does not accompany them is found in the context of a debate over the validity of resurrection (Mark 12:18-27; Matt 22:23-33; Luke 20:27-40). In the book of Acts, the Sadducees are associated with the Jerusalem leadership – either with the Temple authorities (4:1), the high priest (5:17), or the Sanhedrin/Council (23:1-7).

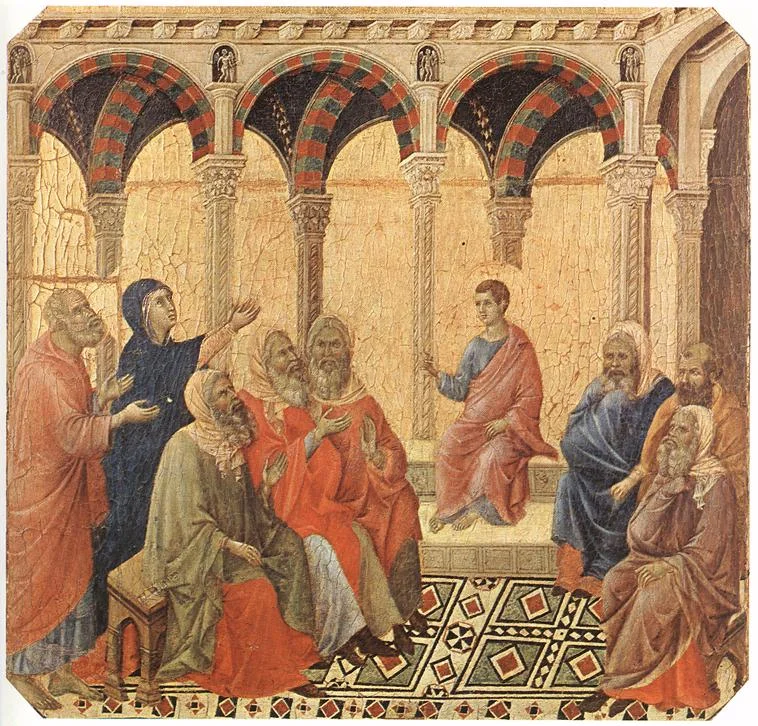

Fig. 4.14: Duccio di Buoninsegna, “Young Jesus Teaches in the Temple” from Luke 2:46-51. Pharisees and Sadducees are depicted. Museo dell’ Opera Metropolitana del Duomo, Siena, 1308-11.

Historians have also noticed an apparent inconsistency between the New Testament and the Jewish sources. The New Testament does not consistently represent the same rivalry between the Pharisees and Sadducees that we find in Josephus and rabbinic literature. In Matthew, the Sadducees and Pharisees are often placed alongside one another as if they were somehow similar, or working as a team. On several occasions Matthew unites them as common opponents of Jesus by using phrases like “Pharisees and Sadducees coming for baptism” (3:7), “leaven of the Pharisees and Sadducees” (16:6), and most surprisingly, “teaching of the Pharisees and Sadducees” (16:12). Matthew’s interest does not lie in the differences or similarities between the two groups. They function as literary antagonists in the development of Jesus’ identity and mission. The modern reader must therefore consider contexts when determining the accuracy of such descriptions.

4.2.3 Essenes

Like the Pharisees, the Essenes seemed to have originated from the Hasidim, who protested against the political and religious policies of the Hasmoneans. Unfortunately, our information about them is scattered and incomplete. Among the most plausible reconstructions is the hypothesis that the Essene community was founded by the “Teacher of Righteousness,” who criticized the Temple establishment, especially the high priest, during the reign of Alexander Jannaeus, king of Judea (103-76 BCE). Others have argued that the “Teacher of Righteousness” founded the Essene community earlier in opposition to Jonathan, the Maccabean high priest, during the middle of the second century BCE. Whatever the specific cause, the Essenes moved away from the Temple in Jerusalem, which they regarded as corrupt and its priesthood as evil. Like the Sadducees, the Essenes disappear from the historical record after 70 CE. Historians surmise that the Essene communities fell victim to the Roman onslaught against the Jews between 66-70 CE.

The Essenes are most well known for their possible connection to the Dead Sea Scrolls that were discovered in the late 1940s in caves by the Dead Sea. Since the first cave is situated about a kilometer north of Wadi Qumran, the documents are also called the Qumran scrolls and the group associated with them is referred to as the Qumran community. Some hypothesize that the writers and/or collectors of the Dead Sea Scrolls were members of an Essene-like group (more is said about the documents below). There were colonies of Essenes throughout Judea, both in the wilderness and in urban areas. The Essene settlement near Qumran may have been an all-male community living in isolation, similar to later (Christian) monastic practices. Josephus describes the Essenes as renouncing pleasure, opposing marriage, and adopting young children in order to instruct them in their ways. He goes on to say that they wore white garments, lived communally, were sober, and preferred silence (War 2.8.2–11 §§119–158).

Fig. 4.15: A cave at Qumran where some of the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered.

The Essene legalistic and ritualistic practices were the most rigorous of all the Jewish sects. The group at Qumran even abstained from defecation on the Sabbath. Their existence was predicated on the hope that God would intervene in their lifetimes and bring about an apocalyptic end to evil (which included the Temple establishment). They saw themselves as living at the end of the age, as agents of righteousness that would hasten the final cataclysmic battle through disciplined religious practices, such as baptism, ritual purity, keeping of the Sabbath, scripture reading, and prayer. As part of the arrival of the messianic kingdom, they awaited the appearance of several end time figures, including a great prophet like Moses, a royal messiah like King David, and a priestly Messiah like Aaron, the brother of Moses.

Fig. 4.16: Ritual bath, called a mikveh, found at Qumran.

Although the Essenes are never mentioned in the New Testament, their beliefs, practices, and writings have forever changed the way that scholars understand early Judaism, and by extension early Christianity. One of the more interesting parallels between the New Testament and the Essenes is found in the ministry of John the Baptist. Both the Essenes and John were rooted in the biblical theological traditions centering in the wilderness and on ritual bathing. Both lived in the wilderness. Both had a vivid sense of impending crises, namely that divine judgment would come very soon. Both had messianic expectations. Both awaited the coming of the Holy Spirit, and both grounded their missions on Isa 40:3 (“In the wilderness, prepare the way of the Lord”). Scholars speculate that Jesus may have also been influenced by Essene teaching since he was a disciple of John’s before venturing out on his own ministry.

4.2.4 The Fourth Philosophy

Fig. 4.17: Ruins of Gamla (today in the Golan Heights), which was the site of a Roman siege against Jewish rebels in 67 CE. According to Josephus (War 4.1-83) 4000 residents were slaughtered, while another 5000 were killed or injured fleeing down the mountainside.

By the first century, the “politics of violence” was familiar to everyone. The success of the military campaigns of the Maccabees against the Seleucids influenced waves of similar guerrilla movements against the Romans. One of these resistance groups, founded by Judah the Galilean and Zadok the Pharisee, is called “The Fourth Philosophy” by Josephus. There is very little evidence regarding this group, leading some scholars to believe that they were an invention of Josephus, or an inconsequential group chosen as a scapegoat for starting the war with Rome. The report is that this resistance movement acquired many followers who engaged in violent uprisings. They refused to pay taxes to Rome, they regarded any loyalty to Caesar as sinful, and they were constantly trying to spark revolts—one of which led to the destruction of the second Temple in 70 CE. It is proposed that, during the Jewish war with Rome, they took the name “Zealots” as an official designation. The Zealots made their last stand in the famous siege at the mountain fortress of Masada.

The members of “the Fourth Philosophy” were bound by a passion for freedom and zeal for God. Many were willing to be tortured and die rather than be dominated by a foreign power. Josephus describes them as sharing many of the beliefs of the Pharisees, apart from their violent tactics and self-sacrifice for the cause of political freedom (Ant. 18:23–5).

4.3 Beliefs, Practices and Institutions

The beliefs and practices of the Jewish religion in the first century were foundational for early Christian formation. Jesus was a Jew whose mission was the restoration of Israel, and not the founding of a new religion. For his earliest followers, their Jewish heritage provided the religious language, concept of God, the scriptures, rituals, notions of faith, law, grace, obedience, justice, eschatological expectation, and messianic hope that gave expression to their understanding of Jesus’ messianic identity. It is no exaggeration to say that early Christianity in general and the New Testament in particular cannot be properly understood without a familiarity with early Judaism.

4.3.1 Monotheism and Election

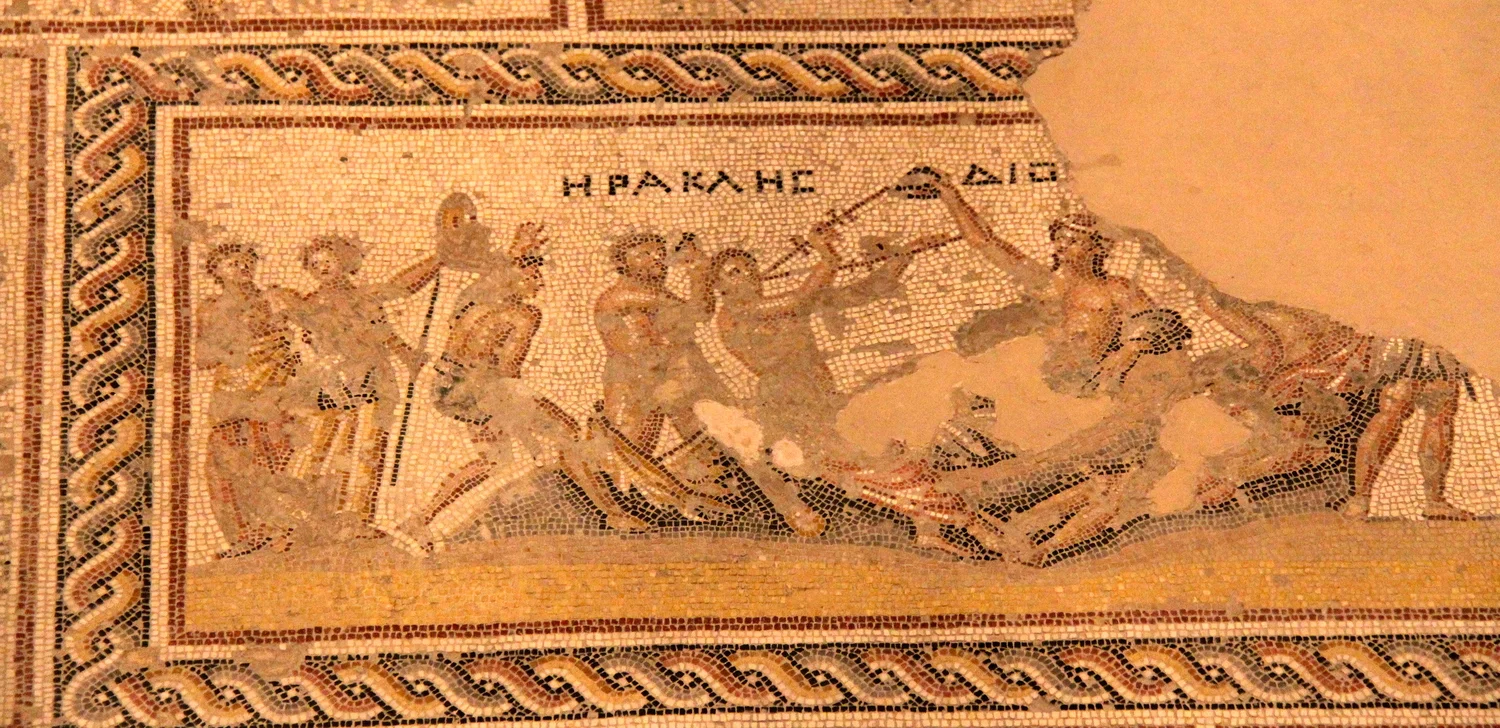

The most distinguishing feature of Judaism in the context of the Greco-Roman world was its monotheism, the belief in one God, to the exclusion of all others. However, the Jewish people were not always monotheistic. The development of monotheism in the history of Israel is long and complex. Israel’s development of monotheism stems from the polytheistic cultures of the Ancient Near East. Before monotheism took root, Israel believed that Yahweh was the supreme god over all the other gods. Eventually, well before the first century, the Jews came to believe that Yahweh was the only god. This traditional understanding of Jewish monotheism has recently been challenged, however. Some scholars today argue that while many Jews in the first century worshiped Yahweh as their ethnic God, they may have also believed in the existence of the Roman deities. Thus they were monotheistic in practice, but not necessarily in belief.

Fig 4.18: Floor mosaic from the Tzippori synagogue, Sepphoris. 5th century. The entire floor of the synagogue is covered with mosaics depicting scenes from both the bible and the Greek mythology. This scene depicts the divine hero Heracles (Roman Hercules), the son of Zeus and Alcmene, in a drinking contest with Dionysus, the god of wine.

In conjunction with monotheism, the Jews of the first century believed that they were the elect people of God, the chosen race that was given privilege and would one day be restored. The identity of election was rooted in the biblical traditions of Yahweh’s special favor and guidance extended to Abraham, Moses, David, and the prophets. In the letter to the Romans, Paul seizes upon Israel’s elect status, but appropriates it for his new theology. Paul argues that national Israel was elected for the purpose of bringing salvation to the whole world. Unfortunately, despite all of the blessings and grace, Israel failed to complete its vocation. Paul goes on to say that God was nevertheless faithful to his covenantal promise by electing another Israel, namely the messiah, who fulfills the promise of salvation to the world.

4.3.2 Torah

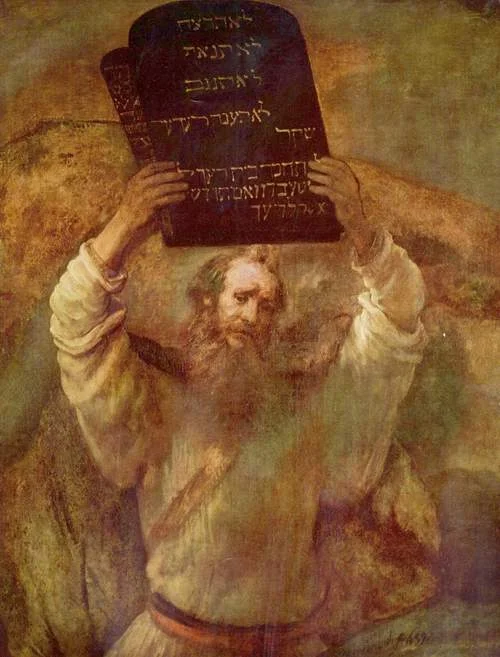

Fig. 4.19: Jekuthiel Sofer’s Decalogue (Ten Laws) on parchment. Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana, Amsterdam, 1768.

Another identifying feature of the Jewish religion (past and present) is the reception of Torah, which conveys “instruction” or “teaching,” but is usually translated “Law.” As an elect people of God, the covenantal obligation of the Jews was to keep the requirements of Torah. These included laws concerning morality, ceremonies of worship, rituals, communal life, family structure, and international politics. What is more, the law requires a disposition of love and honor toward God. The giving of the Law through Moses was not considered as a hardship or an onerous catalogue of rules imposed on the people, but rather as an offering of mercy, grace, and privilege.

In addition to referring to the covenantal obligations of the Jewish people, the term “Torah” also refers to the first five books of the bible, which are traditionally credited to Moses, but were likely written many centuries after he would have lived. Today, we call these five books the “Pentateuch” (which means “five scrolls”). These are Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy.

Fig. 4.20: Rembrandt, Moses with the tablets of the Law. Gemaldegalerie der Staatlichen Muzeen zu Berlin, 1659.

One of the biggest misconceptions among Christians is that Judaism was a legalistic religion that required obedience to the Law in order to receive God’s favor and salvation. Among Protestants, the dichotomy between the Law of the Jews and the grace of the Christians goes back to the early part of the Reformation in the sixteenth century. The Torah, however, was never understood as a checklist of works that one had to complete. The Jews understood (and still understand) the Torah as a gift given by God to help his people live life to its fullest in response to the grace that God has bestowed.

After the Maccabean Revolt, certain laws, called the “works of the law,” served as identity markers for Jews. In other words, those who did not fulfill the so-called “works of the law” were not regarded as Jewish. These typically included circumcision, Sabbath, and certain dietary restrictions. Paul engages in this discussion in the letters to the Romans and Galatians when he confronts fellow Christians who want his new gentile converts to complete their faith through the practice of the “works of the law,” especially circumcision.

4.3.3 Messianic Expectation

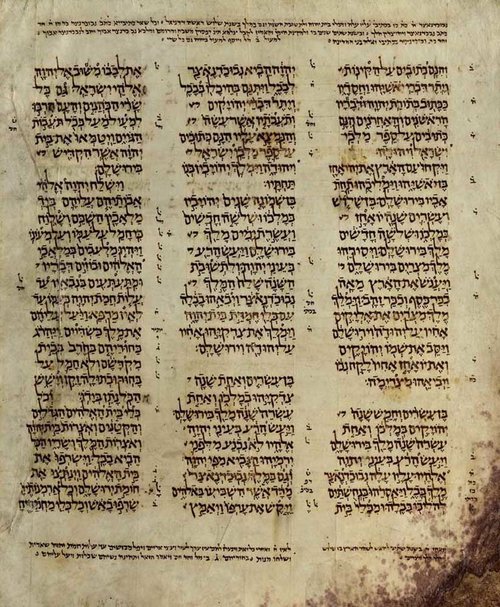

Fig. 4.21: A page from 1QS (Manual of Discipline), which foretells two messiahs. In one passage, we read, “And they shall not depart from any counsel of the law to walk in all the stubbornness of their heart, but they shall be governed by the first ordinances in which the members of the community begin their instruction, until the coming of the prophet and the messiahs of Aaron and Israel” (1QS 9.9b-11).

By the first century, most Jewish people had an inherent expectation of a better life. The hope of God coming to restore his people both politically and spiritually was part of the Jewish psyche after centuries of foreign occupation. Beliefs among Jews varied, but most expected some kind of completion of the present age and the dawn of a new one.

Conceptions of “the last days” or an “end of the age” are today called eschatology (from the Greek eskatos, meaning “last”). Part of the Jewish hope included some form of messianic expectation. These varied as well. Some awaited one messiah (Hebrew for “anointed one”), some expected two messiahs, and others may have awaited even three.

The messianic figures included the prophetic messiah, the priestly messiah, and/or the royal messiah. However, the popular conceptions of messiah neither included his death at the hands of the gentiles, nor his resurrection. The expectation of a kingly messiah, rooted in the biblical tradition of David, who would deliver the Jews from the oppression of the Romans certainly circulated in the first century, but did not seem to be widespread or consistent. When the early Jewish texts that interpret messiah according the Davidic tradition are surveyed, they do not consistently ascribe the same function to him.

For example, the messiah in 4 Ezra 12:32 who “will arise from the posterity of David” appears closer to Daniel’s Son of Man coming as a warrior on the clouds to deliver the righteous remnant and judge the wicked. Another example is found in the writings of Josephus, who records numerous resistance movements taking place after the death of Herod the Great in 4 BCE. Some of these movements hailed their leaders as royal messianic figures in the line of David, as men who were committed to the military overthrow of Roman occupation.

Fig. 4.22: Caravaggio’s “David with the Head of Goliath. Museo e Galleria Borghese, 1607.

For the early Christians, David stands at the midpoint of an unbroken continuity between Abraham and Jesus. They believed that the promise of descendants (and a great nation) made to Abraham corresponded also to David, and found its ultimate fulfillment in Jesus whose messianic work was for the benefit of the world. In the synoptic gospels, Jesus is occasionally associated with David, usually as his son (meaning his descendant). For Paul, Jesus is “descended from David according to the flesh, established as Son of God in power according to the spirit of holiness through resurrection from the dead” (Rom 13-4).

Throughout the New Testament, the messianic identity of Jesus is central, rich, multi faceted, and usually influenced by early Jewish religious thought. Many of the early Christian appropriations of these ideas are presented throughout the rest of this book.

4.3.4 Sabbaths and Festivals

The practice of keeping the Sabbath was another unique feature of Judaism. In the Greco-Roman world, there were few designated holidays or work-free days. For Jews, the seventh day of every week was devoted to rest, worship, and a communal meal in commemoration of God’s rest after the creation. Many gentiles considered this practice to be extremely lazy. The observance of Sabbath has its origins in the Pentateuch, primarily in Genesis 1-2 and Exodus 16. Modern research into the origins of the Sabbath is unfortunately inconclusive, though there is strong evidence that it may have Babylonian roots. By the first century, the observance of Sabbath was a central Jewish identity marker.

Fig. 4.23: Wall painting of Moses and scenes from the Exodus, Duro Europos Synagogue, Syria. 3rd century.

During the span of a year, Jews celebrated three festivals that brought pilgrims to Jerusalem. Each one of these is included in the New Testament. John’s gospel is particularly rich in symbolically linking these celebrations with the identity and mission of Jesus. The first festival of the year, during the spring, was the seven-day festival of “Unleavened Bread,” which commemorated Israel’s exodus from Egypt. The Passover meal marked the beginning of the celebration. Specifically, the meal was a celebration of the Angel of Death passing over those households that had smeared lamb’s blood over their doors (Exodus 13:3-10). The feast included lamb, which commemorated the sacrifice, unleavened bread, which commemorated the haste of the exodus, and bitter herb, which symbolized the harsh conditions of slavery.

Fig. 4.24: Sinai Desert

The second festival was called the festival of “Weeks” or Pentecost. It received the designation “Weeks” because it was celebrated seven weeks (or as it was sometimes said, a “week of weeks”) after the festival of Unleavened Bread. The term “Pentecost” (which means “fifty” in Greek) is simply a rounding up from forty-nine days (seven weeks) to fifty days. This one-day festival had its roots in the thanksgiving and celebration of the barley and wheat harvests (Lev. 23:15-21). The agricultural component of the festival eventually gave way to a thanksgiving and celebration of the giving of Torah at Sinai (Deut. 16:12), which took approximately fifty days to reach after leaving Egypt (Exod. 19:1).

The third festival was called “Tabernacles“ or “Booths.” This festival celebrated the completion of the harvest cycle in the final gathering of the grapes from the vineyards (Exodus 23:16; 34:22). During the festival, which lasted a week, celebrants went out into the vineyards and lived in portable shelters, from which derives the terms “tabernacles“ or “booths.”

Fig. 4.25: Pool of Siloam, Jerusalem.

Theologically, Tabernacles focused on the retelling of the exodus story, when the Israelites lived in the wilderness (Lev. 23:34-44; Deut. 16:13-15). The celebration in the first century included several rituals that symbolized God’s provision for the Israelites in the wilderness. In one part of the celebration, God was praised for providing much needed rain to sustain agricultural life. The commemoration was rooted in the story of the water-gushing rock in the wilderness. While worshippers sang Psalms 113-118, water from the fountain of Siloam was poured onto the Temple altar as a libation to signify the hope that salvation would one day come from Jerusalem to all the nations (m. Sukk. 55; cf. Ezek 47:1-12; Zech 13:1; 14:8). The pouring out of water was an invocation for rain, which was vital in an arid climate, but it also symbolized the giving of the Holy Spirit, who gives and sustains spiritual life.

It is remarkable how much the background of this ceremony provides meaning for John’s portrayal of Jesus in 7:37-39, in which Jesus is depicted as the rock from which rivers of life flow. As in the Tabernacle festival, John equates water with the Holy Spirit, which is promised after Jesus’ death. In light of this background, John is saying that the prayers of the celebrants have been answered in the giving of the Spirit by Jesus.

Fig. 4.26: A ram’s horn (shofar) would have commonly been used as a trumpet in the ancient world for Jewish religious ceremonies.

The Jews celebrated other festivals that did not necessarily require pilgrimage to Jerusalem. One of these was the festival of Trumpets, which was celebrated on the first day of the same month of Tabernacles (Tishri). Trumpets were sounded to remind God to remember his promise and covenant. By the first century, the practice was also to frighten away Satan and to awaken sinful Israel to repentance (Num. 10:10). Another important celebration during the same month, after Trumpets and before Tabernacles, was the Day of Atonement (Leviticus 16). This day was the climax of the calendar year. The Temple was cleansed to ensure its ritual purity and the High Priest confessed Israel’s sins. To these can be added the festival of Purim, which commemorated the story of Esther and the deliverance of the Jewish people, and the festival of Lights or Dedication (today known as Hanukkah), as it appears in John 10, which commemorates the rededication of the Temple by Judas Maccabaeus.

4.3.5 The Temple

The Temple was the focal point of religious activity, not only for Jews living in Judea and Galilee, but also for those in the Diaspora. The Temple attracted many Jewish pilgrims from around the empire, especially for the celebration of Passover. Most would arrive on Palestine’s shores, usually at the port of Jaffa (today’s Tel Aviv) by boat and then travel south for three days until they reached Jerusalem. The glistening white marble structures with sections overlaid with gold, which covered about twenty-six acres, would have been an impressive sight as pilgrims neared the city. Pilgrims contributed significantly to the economy of Jerusalem. They needed food, lodging, sacrificial animals, and other supplies. Josephus writes that Passover in 65 CE was celebrated by two million and seven hundred thousand people, with only 200 priests (War 6.425). Though it is hard to know how inflated this number might be, it is obvious that Josephus is indicating a vast crowd of pilgrims.

Fig. 4.27: Model of the entire Temple complex in the 1st century before its destruction by the Romans. Israel Museum, Jerusalem. The section of the Temple Mount which remains today (called the Western Wall) is in this photo part of the shadowed wall with the two arches.

The Temple was also an ethnic, political, and economic center that wielded justice and power. As a form of taxation, Jews were required to pay a half-shekel annually. The High Priest and his family, under the oversight of the Roman prefect, controlled the operations of the Temple, including the collection of the taxes. Josephus calls the chief of everyday operations stratēgos (War 2.409), a military term meaning “captain,” who may have also been in charge of the Jerusalem markets. Levite families were responsible for the daily function of the Temple. Their responsibilities included the maintenance of proper structure, security, and purity. Since certain areas of the Temple complex were restricted to Jews and priests, the security force guarded the gates of the Temple and had the authority to severely deal with transgressors. Gentiles could enter the outer court, but inscriptions in Latin and Greek warned them severely not to enter the inner courts, which were reserved only for Jews.

Fig. 4.28: Model of the Temple, Israel Museum, Jerusalem. Click the image and take a 3d tour of the Temple.

Just outside the Temple proper stood an altar for burnt offerings and a “laver,” which was a large basin full of water that the priests used for washing. Inside the first room, curtained from the outside with a heavy veil, stood three pieces of furniture: (1) the menorah, a seven-branched golden lamp stand that burned olive oil, (2) a table stocked with bread that represented God’s providential presence and (3) a small altar for the burning of incense. Another heavy veil curtained off the innermost room, called the Holy of Holies, into which only the High Priest entered once a year on the Day of Atonement. During the time of the First Temple (built by Solomon), the Ark of the Covenant was the only piece of furniture placed in the Holy of Holies. Its disappearance or destruction some time prior to the Babylonian sacking of Jerusalem remains a mystery, though there is a small temple in Ethiopia whose priests claim to have it. Unfortunate, since entry is only limited to the local priests, their claim cannot be verified.

Daily operations in the Temple included private sacrifices, burnt offerings for the whole nation, burning of incense, prayers, priestly benedictions, the pouring out of wine as a libation (liquid offering), the blowing of trumpets, and chanting and singing. Sabbaths, festivals, and other holy days included additional ceremonies.

4.3.6 Synagogues

Fig. 4.29: Remains of the synagogue at Capernaum built in the 4th century CE.

Another important political/religious institution was the synagogue (which means “an assembly”). It has a long and complicated history that seems to be an amalgamation of a prayer house, a school, and a community hall. Some scholars have speculated that the synagogue began as an informal assembly, not a building, during the Babylonian exile. Others trace its origin to prayer assemblies in the Diaspora during the Hellenistic period. Since there were many kinds of synagogues, no single definition fits them all. Functions varied from place to place.

Fig. 4.30: The dark basalt rocks below the 4th century remains of the Capernaum synagogue are the foundations of the town from the 1st century CE. The 1st century synagogue with which the Apostle Peter was familiar (since Caperneum was his home town) would have been located in the same place.

In first century Palestine, synagogues were common throughout the villages. It is unlikely that any single group or office controlled all of the synagogues. Contrary to the opinions of some scholars, there is little evidence to suggest that the synagogues were connected with the scribes and Pharisees, and much less that they were a Pharisaic invention. The synagogue appears to have been predominately a democratic lay organization with no political party controlling the standards of liturgy. The evidence is unclear whether in the first century a synagogue was a specific building or merely any meeting place, which included homes, shops, and assembly halls.

Like today, the synagogue was the location of local religious services. The typical synagogue service consisted of the following sequence: (1) recitations of the Shema (Deut 6:4, later expanded to include verses 5-9; 11:13-21; Num 15:13-41) and of the Shemone Esreh (a series of praises to God), (2) prayer, (3) singing of Psalms, (4) readings from the Hebrew scriptures interspersed with a Targum (paraphrase in the commonly-spoken Aramaic language), (5) a sermon (if someone competent was present), and (6) a benediction. In the first century, the synagogue also functioned like a town hall, where a variety of community affairs were handled, such as fund-raising, public projects, funerals, education, and the resolution of social conflicts.

Fig. 4.31: Remains of a 3rd century CE synagogue at Dura Europos, Syria. The interior is adorned with biblical scenes. It is one of the most elaborate synagogues from antiquity.

An elected official presided over the meetings, introduced guests, and delegated reading and preaching responsibilities to other members of the synagogue. Because qualified teachers were usually invited to give a sermon or to read a scripture text, both Jesus and Paul took advantage of the opportunities to communicate their teachings.

4.4 Jewish Writings

The Jewish people were very prolific writers. At the heart of their writings were their scriptures or the biblical writings, which were believed to contain the words of God communicated through Moses, the Prophets, and other chosen agents, like David and Solomon. Alongside the scriptures were numerous other writings that expressed almost every aspect of early Jewish life.

4.4.1 Biblical Writings

Fig. 4.32: Genesis 1 from a 13th century Hebrew Bible. Bodleian Library, Oxford.

Over several centuries, the cultural and linguistic shifts in Palestine and the Diaspora gave rise to at least five different versions of the Jewish scriptures that were either completed or were emerging in the first century CE. Scholars have referred to these as the Masoretic Text (MT), the Dead Sea Scrolls Bible, the Septuagint, the Samaritan Pentateuch, and the Targums. Each one of these has a complicated textual history with varied textual traditions that cannot possibly be tackled here. What is important to understand at the introductory level is that during the first century none of these versions represented a standardized text. There was no standard version of the bible.

The designations that scholars use for the ancient versions of biblical writings refer to textual traditions or families of texts. Moreover, some of the designations are anachronistic, meaning that they have been acquired after the first century. For example, as is discussed below, there was not an actual Masoretic Text in the first century, but there were families of manuscripts that eventually became the basis for the Masoretic Text. Another example is the Targum, which in the first century was not a written text at all, but was in part an established oral tradition recited in synagogue settings.

The Masoretic Text

The term “Masoretic” comes from a name given to a school of scribes who were called Masoretes. They are first identified in the rabbinic literature of the fifth century CE in which they are portrayed as scribes who are concerned with accurate copying and grammatical interpretation of the Hebrew Scriptures, but the tradition of their practice is certainly much older.

Fig. 4.33: Hebrew script with pointing. The symbols above and below the characters represent vowels.

The Masoretes are best known for the notes, called the Masora, that were appended to the text. This tradition, which may go back to the first century, made a distinction between what was written (called the ketib) in the text, and how it was to be read (called the qere). The Masoretes are also commonly known for adding vowels, known as “vowel points” or “pointing,” to the consonantal Hebrew text in order to prevent corruption of the text. Unlike English, the earliest Hebrew alphabet is made up only of consonants, a few of which can sometimes indicate the presence of various vowel sounds. Apart from the Masoretic text, most of the Hebrew writings from the ancient world (and even modern Hebrew writings) are written without vowels. It can be compared to writing the English word “bt.” Without the vowels, we are not sure if the word is “bat,” “boat,” “bite,” or some other possibility. By addition vowels, the Masoretes eliminated options for alternate readings.

Fig. 4.34: A page from the Aleppo Codex (10th century CE), which together with the Leningrad Codex comprises the foundations for modern the modern Hebrew Bible.

The MT is today the authoritative textual version of Judaism and Western Christianity (Roman Catholicism and Protestantism). It is what Jewish people call Tanakh and what Protestants and Roman Catholics call the “Old Testament.” Although we possess a few fragments from the sixth to the eighth centuries, our oldest manuscript, which is not a complete text of the MT, is dated to the ninth century. Modern versions of the Hebrew Bible are all based on the Leningrad Codex, dated to 1008 CE, which is a complete text of the MT.

The Dead Sea Scrolls

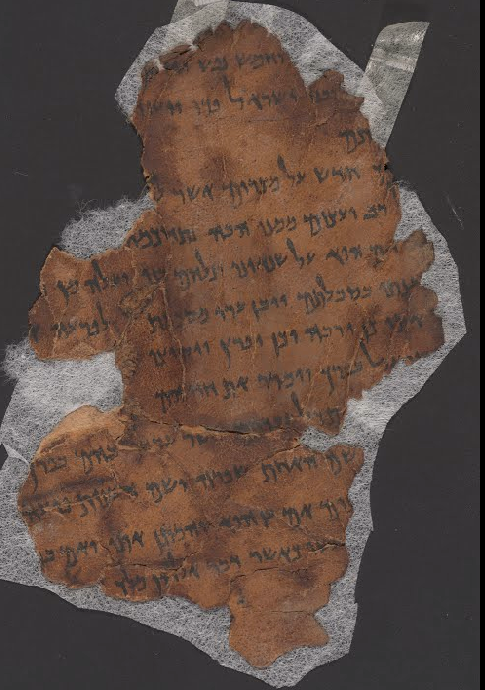

Fig. 4.35: 4QGenesis-Exodus. Most of the biblical manuscripts found at Qumran are even smaller than this fragment.

Another version of the scriptures (if we can call it that), written mostly in Hebrew, was found among the Dead Sea Scrolls, which are commonly dated between the second century BCE and the first century CE. Often called the greatest literary or archaeological discovery of the twentieth century, these biblical and non-biblical writings have altered forever how we understand the scriptural canons, the religious groups, and religious thought within early Judaism and Christianity.

Among the 900 (or so) documents discovered in eleven caves, over two hundred have been identified as biblical texts representing all of the writings found in the MT canon except Esther. Not all biblical texts, however, are equally represented. Prominence appears to have been given (in order of frequency) to the Psalms, Deuteronomy, Isaiah, Genesis, and Exodus.

The Septuagint

Fig. 4.36: Codex Sinaiticus (part of Isaiah 42). British Library, 4th century CE.

The designation “Septuagint” is often used to refer to the Greek translation of a Hebrew source that served as the primary version of the bible for the New Testament writers and later many of the Church Fathers. It continues to be the official version of the Old Testament in Eastern Orthodoxy. The term comes from the Latin Septuaginta, which means “seventy,” and is today frequently abbreviated using the Roman numerals LXX.

The LXX differs from the MT in a variety of ways. Some differences are significant, but most are minor. The most prominent difference is the Greek version of Jeremiah, which is about 2700 words shorter than in the MT. The book of Job is also shorter in the Greek, but not to the same extent. By contrast, the Greek version of 1 and 2 Samuel is considerably longer and more polished than in the MT. Daniel also contains an additional 67 verses between 3:23 and 3:24. The differences are often explained by pointing out that the MT is a later tradition and may not have accurately represented the source used by the Greek translators. In other words, the Greek translators probably used another, slightly different Hebrew source.

The Samaritan Pentateuch

The Samaritan Pentateuch (SP) originated primarily for theological reasons, as a response to Hasmonean Judaism, around 100 BCE. The history of the Samaritans and their tumultuous relationship with the Jewish people is retold in different ways and each is difficult to substantiate. Many scholars date the separation to the Hasmonean period when the High Priest and king John Hyrcanus laid siege to Shechem and decimated the Samaritan temple on Mount Gerizim (111-120 BCE).

One of the most distinguishing features about the Samaritans is their insistence that Mount Gerizim, instead of Jerusalem, is God’s designated center of worship. The earliest accounts in the bible associate this site with Abram’s first altar (Gen 12:6) and Jacob’s well (Gen 33:18-20). It was also the site (along with Mt. Ebal) where the Israelites assembled to hear the Law (Deut 11:29; 27:12; Josh 8:33). Today it is known as Jebel et-Tor and is located on the south side of the Nablus Valley, opposite Mount Ebal. A synagogue on the site is still used for worship by a dwindling Samaritan community.

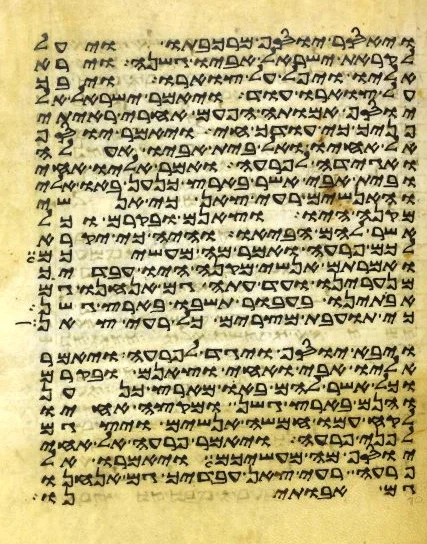

Fig. 4.37: Page from the Samaritan Pentateuch. Rylands Collection, 13th century CE. The script is a Samaritan alphabet derived from the Paleo-Hebrew, which was commonly used prior to the Babylonian captivity (6th century BCE). There are about 6000 differences between the MT and SP, though most are minor and insignificant.

The emergence of the SP is difficult to ascertain, but it is not unreasonable to trace some part of it to the second century BCE when Samaritan worship at Mount Gerizim was institutionalized. A Samaritan legend suggests a much earlier date, tracing it to Abisha “son of Phineas, son of Eleazar, son of Aaron,” who is regarded as the founding priest of Israel. The problem with the legend is that it is written in an old paleo-Hebrew script which was in use during the early Roman and late Hasmonean periods, and so appears to post-date the MT. In addition to grammatical and historical alterations, simplification of archaic philology, and clarification of earlier concepts and ambiguities, SP appears to make significant theological changes to the MT tradition. One of the most telling examples is the legitimizing of Mount Gerizim as the center of worship in Exodus 20.

While the textual tradition of the SP is closely tied to the relatively sectarian community from which it emerged, there are traces of its textual tradition in the New Testament, especially Acts 7 and Heb 9:3. It is difficult to know how these traditions were accessed, since it is unlikely that early Christians would have had the SP at their fingertips. In addition to these, there are texts among the Dead Sea Scrolls that seem to exemplify an earlier tradition, from which SP likely emerged.

The Targums

Fig. 4.38: Liturgical Torah reading in the synagogue.

The Targums, or Targumim, (meaning “translations”) are Aramaic paraphrases of the Hebrew bible. They emerged as oral interpretive traditions that were developed within worship contexts (probably synagogues) sometime during the Second Temple period when Aramaic was the common language. The popularity of Aramaic among the Jews who returned to Palestine from Babylon is reflected in Neh 8:1-8, which retells how Ezra’s public reading of the Law required interpreters/translators so that the people could understand it.

Eventually, beginning in the second century CE, the oral interpretive traditions that were handed down from one generation to the next began to be recorded and eventually permanently preserved in what is called the Targums. Today the Targums are found in three versions, Onkelos, Neofiti, and Pseudo-Jonathan, each named after its supposed translator. The Targums are especially well known for their rather loose translation techniques. They reveal interpretive practices that attempt to contemporize their Hebrew source.

There is ample evidence to suggest that Jesus and some of the New Testament writers were familiar with the Targumic traditions while they were still in oral form. One example comes from Jesus’ quotation of Isa 6:9-10 in Mark 4:12. In contrast to the disciples, who are given the secret of the kingdom of God, Jesus says that to those on the outside everything is given in parables in order that,

they may indeed look, but not perceive,

and may indeed listen, but not understand;

so that they may not turn again and be forgiven (NRSV)

The last part of the quotation (“and be forgiven”) only appears in the Targum, which suggests that Jesus or Mark (or both) were familiar with this tradition.

4.4.2 Non-Biblical Writings

The amount of non-biblical Jewish writings from the Second Temple period is truly staggering and their value for understanding the New Testament cannot be exaggerated. In addition to providing us with the cultural, social, and political framework within which Jesus and his disciples lived, many of the religious and philosophical ideas in them are the precursors to early Christian thought, such as notions of the afterlife, hell, heaven, angels, an apocalyptic end of the age, and even resurrection. Unfortunately, most lay readers of the New Testament are not familiar with many of these writings. They may, however, be familiar with the categories into which these writings have been placed by scholars, namely the Apocrypha, the Pseudepigrapha, and the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Apocrypha

The designation “apocrypha” (plural of “apocryphon”) is a transliteration of a Greek word that meant at one time “hidden secret” or “hidden away.” Eventually the designation became synonymous with “false,” be it a written work or a saying. The reason that these writings were categorized as “hidden” and eventually “false” goes back to their exclusion from the Jewish and Protestant canons of scripture. Among these groups, those who furtively regarded these writings as authoritative and valuable kept their assessment to themselves, and thus they were regarded as being “hidden” from the masses of the uninitiated.

After the sixteenth century, when Protestant groups began to forge their distinctive identities, most regarded these writings as false or apocryphal because they were excluded from the canon. Today most of these books are accepted as inspired and canonical in Roman Catholic, Orthodox, and Coptic traditions, which constitutes the majority of Christians around the world. Among these groups, the writings are sometimes referred to as “deutero-canonical” (meaning “secondarily” canonical).

Fig. 4.39: Wojciech Korneli Stattler, "Maccabees." National Museum of Krakow, Poland. 1842. Inspired by the stories in 1 and 2 Maccabees, the painting depicts Antiochus III confronting the Hasmoneans.

The Apocrypha contains fifteen writings of varied genres that were written in the first and second centuries BCE (except parts of 2 Esdras). Included are historical books (1, 2 Maccabees, 1 Esdras), wisdom literature much like Proverbs (Wisdom of Solomon, Sirach or Ecclesiasticus), romantic and heroic tales (Tobit, Judith, Susanna, Additions to Esther), ethical writings (Baruch, Letter of Jeremiah, Bel and the Dragon), prayers (Prayer of Azariah and the Song of the Three Children, Prayer of Manasseh), and one apocalyptic work (2 Esdras).

Some editions of the bible that contain the Apocrypha place Baruch at the end of the Letter of Jeremiah, resulting in only fourteen books. In other editions there are only thirteen books. Whatever the count, the early Christian writers would probably have known all of these writings to some extent. They do not specifically quote from any of them, but there are numerous parallels that aid in our understanding of the New Testament writers’ appropriation of scripture and its traditions.

Pseudepigrapha

The term “pseudepigrapha” is a transliteration of the Greek word meaning “falsely ascribed.” In the ancient world it was not unusual to write under a different name. When a celebrated figure from Israel’s biblical history was used as a pseudonym (such as Abraham, Enoch, the twelve sons of Jacob, and even Adam) the authoritative value of the writing was probably significantly enhanced. It is difficult to know how many people accepted the pseudonymous authorship as authentic, but it seems to have been an accepted and widespread practice that found its way into Christianity.

Fig. 4.40: “Joseph and Aseneth,” unknown artist. Staatliche Museen, Berlin, c. 1500. The scene depicts the story of Joseph and Aseneth (found in the Pseudepigrapha), which is an elaborate interpretation of Gen 41:45 explaining how the righteous Joseph could have married Aseneth, the daughter of a pagan priest named Potiphera.

In modern scholarship, “pseudepigrapha” is used as a classification for an anthology of Jewish writings that stems from about the sixth century BCE (Ahiqar) to the ninth century CE (Apocalypse of Daniel), though predominantly they range from about the second century BCE to the second century CE. The writings cover a variety of topics, genres, styles, themes, and theological ideas that are vital for understanding both early Judaism and Christianity. James Charlesworth’s two-volume Old Testament Pseudepigrapha is used today as the standardized anthology of these writings in English.

Like the books in the Apocrypha, the pseudepigraphal writings never made it into the Jewish canon. Unlike the Apocrypha, they also never made it into any of the Christian canons. Apart from the influence of 1 Enoch in Jude 14-15, the New Testament writers do not quote from the Pseudepigrapha, though like the writings of the Apocrypha, there are numerous parallels that help us to better understand of the New Testament.

Non-Biblical Dead Sea Scrolls

Fig. 4.41: Clay jar commonly used at Qumran to store manuscripts. Shrine of the Book, Jerusalem. 1st century CE.

In addition to the discovery of biblical documents, the caves around the Dead Sea also contained non-biblical writings, which represent some of the particular beliefs and customs of the community that lived in this region. The non-biblical scrolls contain a variety of unusual writings, such as the community’s rules of conduct, worship and ritual practices, apocalyptic expectations, prayers and hymns, and biblical commentaries. Although many of the ideas and practices found in these writings represent a form of sectarianism, they are nevertheless very helpful for a fuller understanding of early Christian thought about such topics as messianism, apocalypticism, Jewish identity, and rituals.

Try the Quiz

Bibliography

Primary Sources in English

Brenton, L. C. L., trans. The Septuagint Version of the Old Testament. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1986.

Charlesworth, J. H., ed. The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha. 2 vols. Garden City: Doubleday, 1983-85.

Josephus. Jewish Antiquities. 9 vols. Translated by H. St. J. Thackeray, et al, Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1930–65.

———. The Jewish War. 3 vols. Translated by H. St. J. Thackeray. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1927–28.

McNamara, M., ed. The Aramaic Bible: The Targums. 19 Volumes. Collegeville, Minn.: Liturgical Press, 1987-1992.

Metzger, B. M. and R. E. Murphy, ed. The New Oxford Annotated Apocrypha. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Neusner, J., trans. The Mishnah: A New Translation. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1988.

Vermes, G. The Dead Sea Scrolls in English. 3d ed. New York: Penguin, 1987.

Whiston, W., trans. The Works of Josephus. Updated Edition. Peabody, M.A. Hendrickson, 1987

Wise, M., M. Abegg Jr., and E. Cook. The Dead Sea Scrolls: A New Translation. San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1996.

Secondary Sources

Binder, D. B. Into the Temple Courts: The Place of the Synagogues in the Second Temple Period. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 1999.

Cohen, S. J. D. From the Maccabees to the Mishnah. 2nd edition. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2006.

Collins, J. J. The Scepter and the Star: The Messiahs of the Dead Sea Scrolls and Other Ancient Literature. New York: Doubleday, 1995.

de Silva, D. A. Introducing the Apocrypha. Grand Rapids: Baker, 2002.

Evans, C. A. Ancient Texts for New Testament Studies. A Guide to the Background Literature. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2005.

Flint, P. and J. C. VanderKam. The Meaning of the Dead Sea Scrolls: Their Significance for Understanding the Bible, Judaism, Jesus, and Christianity. San Francisco: HarperCollins, 2002.

Goodman, M. Judaism in the Roman World: Collected Essays. Ancient Judaism and Early Christianity 66. Leiden: Brill, 2007.

Grabbe, L. L. Judaic Religion in the Second Temple Period: Belief and Practice from the Exile to Yavneh. New York: Routledge, 2000.

Hanson, K. C. and D. E. Oakman, Palestine in the Time of Jesus: Social Structures and Social Conflicts. Minneapolis: Fortress, 1998.

Horsley, R. A. “Synagogues in Galilee and the Gospels.” In Evolution of the Synagogue: Problems and Progress. Edited by H. C. Kee and L. H. Cohick. Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press International, 1999. Pp. 46-69.

Jeremias, J. Jerusalem in the Time of Jesus. Philadelphia: Fortress, 1969.

Jobes, K. H., and Moisés Silva. Invitation to the Septuagint. Grand Rapids: Baker, 2000.

Levine, L. I. The Ancient Synagogue: The First Thousand Years. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000.

Lightstone, J. “Sadducees verses Pharisees: The Tannaitic Sources.” In Christianity, Judaism and Other Greco-Roman Cults: Studies for Morton Smith at Sixty. Part Three: Judaism before 70. Edited by J. Neusner. Leiden: Brill, 1975. Pp. 206-17.

Mason, S. Flavius Josephus on the Pharisees: A Composition-Critical Study. SPB 39. Leiden: Brill, 1991.

Neusner, J. “Mr. Sanders’s Pharisees and Mine.” Bulletin for Biblical Research 2 (1992). Pp. 143-69.

_____. From Politics to Piety: The Emergence of Pharisaic Judaism. Englewood Cliffs, NJ.: Prentice-Hall, 1973.

Neusner, J., W. S. Green, and E. S. Frerichs. Judaisms and Their Messiahs at the Turn of the Christian Era. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

Pomykala, K. E. The Davidic Dynasty Tradition in Early Judaism: Its History and Significance for Messianism. SBL Early Judaism and Its Literature 7. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1995.

Porton, G. G. “Diversity in Postbiblical Judaism.” In Early Judaism and Its Modern Interpreters. Edited by R. A. Kraft and G. W. E. Nickelsburg. Philadelphia: Fortress; Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1986. Pp. 57-80.

Purvis, J. D. “The Samaritan Problem: A Case Study in Jewish Sectarianism in the Roman Era.” In Traditions in Transformation: Turning Points in Biblical Faith. Edited by in B. Halpern and J. D. Levenson. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1981. Pp. 323-50.

Saldarini, A. J. Pharisees, Scribes and Sadducees in Palestinian Society: A Sociological Approach. Wilmington: Michael Glazier, 1988.

Sanders, E. P. Judaism: Practice and Belief 63 BCE–66 CE. Philadelphia: Trinity Press International, 1992.

Schürer, E. The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ (175 b.c.–a.d. 135). Vol. 2. Revised by G. Vermes et al. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1979.

VanderKam, J. C. The Dead Sea Scrolls Today. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1994.

Waltke, B. K. “Samartian Pentateuch.” In The Anchor Bible Dictionary. Volume 5. Edited by David Noel Freedman. 6 vols. New York: Doubleday, 1992. Pp. 932-39.

Würthwein, E. The Text of the Old Testament: An Introduction to the Biblia Hebraica. Translated by E. F. Rhodes. 2nd edn. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1995.