Module Three

Religious Background: Pagan Religions and Philosophies

3.1 Introduction

Dividing our first chapters into the categories of political, social, and religious backgrounds is a common approach in most introductions to the New Testament, but it is somewhat artificial because all of these were closely intertwined in the daily life of every person living in the first century. Unlike today, there was no separation of church and state. These categories, however, serve an important purpose for modern New Testament studies. They help us to organize and understand the fragmented historical data, allowing for more convenient retrieval and more accurate comparison with New Testament texts.

Fig. 3.1: Temple of Apollo, Corinth, 6th century BCE.

This chapter and the next are introductions to the religious backgrounds of the New Testament. In this chapter, the focus is on pagan religions and philosophies that circulated throughout the Greco-Roman world. The next chapter is an introduction to early Judaism and its writings. The division between pagan and Jewish religions is somewhat simplistic since it does not account for syncretism and the wide variety of religious expression. For example, many Jews were influenced by Greco-Roman thought, especially those living outside of Palestine. As well, some pagans were attracted to Judaism and even converted, while maintaining pagan ideas and practices. Nevertheless, these divisions, which again are standard in most introductions to the New Testament, serve their purpose for introducing many of the clear distinctive differences between pagan and Jewish religions.

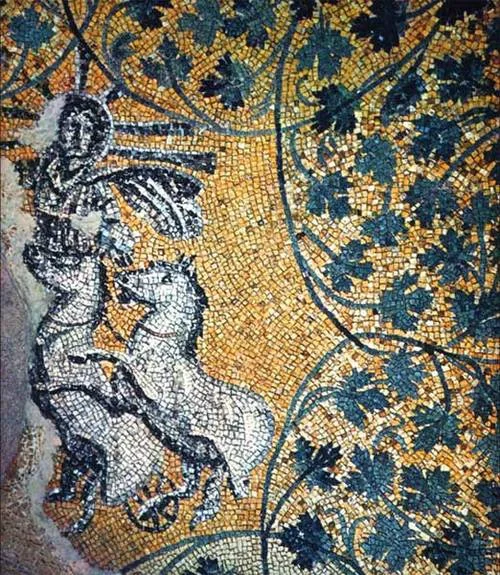

Fig. 3.2: This Synagogue floor mosaic, often called “the Mona Lisa of Galilee,” was discovered at Sepphoris. Although it is dated to the 5th century CE, it serves as an example of Pagan and Jewish syncretism. The figure on the left is believed to be Dionysus.

3.2 Why is Religious Background Important?

The religious background is important for understanding the primary ideas in the New Testament writings along with the origins and development of early Christianity. The reason for this is twofold. First, since early Christianity originated sometime in the middle of the first century, it necessarily relied on its host culture. What this means is that the early Christians appropriated the existing language, concepts, and practices of the culture around them to give expression to their new faith. They could do no other since, as all of us even today, they could only speak or write about things in relation to what they already knew. While the influences were widespread, none was more significant than Judaism. It truly was the cradle of Christianity. For example, in the gospels Jesus is identified with Moses and David. In Paul’s writings, he is the representative of Israel. In Hebrews, he is the great high priest. The second reason why the religious background is important is that it allows us to better understand the opponents and rivals of the early Christians. Quite often the New Testament writings are polemical, meaning that they are arguing against a particular group, concept, or belief. Again, these are primarily Jewish in origin, but they are rarely mentioned. Often they are simply assumed. In this regard the New Testament writings are much like a one-way telephone conversation or a string of text messages from only one sender. A more thorough understanding of the religious world of the first century helps us to better understand the other side of the conversation in which the New Testament writers participated.

Fig. 3.3.: Ruins of the Great Theatre, Ephesus. Grand structures were cultural symbols of Rome’s power and influence.

Essential to any reconstruction of an ancient religion is the critical use of primary sources. Data from these sources must be used in a cautious manner by giving due attention to a variety of critical issues, such as date, the location of writing, the author’s purpose, audience, opponents, and the social setting. Recent study of ancient religions and their texts is increasingly relying on interdisciplinary methods, which allow scholars to approach primary sources from a variety of perspectives. In short, it allows for different questions to be posed to the ancient writings. In particular, there is an increased interest to view first-century groups and individuals within the social fabric of their world, which was radically different from our own. More and more attention is being focused on the practice of “popular” religion among common people as opposed to “official” religion that might be expressed in the writings of the elite. Specific questions that are raised in sociology, social anthropology, and political studies are now being applied to religious texts, and the New Testament is no exception.

3.3 Paganism

When historians speak about pagan religions and philosophies in the Greco-Roman world, they are usually referring to the many beliefs and practices that were neither Christian nor Jewish throughout the Mediterranean basin from the time of Alexander the Great to the Christianization of the Roman Empire in the fourth century. For historians, the term “pagan” does not have the same derogative connotation as it sometimes does in today’s popular speech. It is not a negative term, but simply refers to an individual who practiced one of the many polytheistic religions in the ancient world.

Fig. 3.4: Mosaic of Poseidon and Amphitrite, Herculaneum, 1st century CE. Roman and Greek gods were commonly depicted in the nude or semi-clad.

Pagan religions, or paganism, varied widely across the empire, yet all of the varieties shared a few common traits. Each of these can be contrasted with Judaism and Christianity. First, pagans were polytheistic, meaning that they subscribed to the belief that there are many gods, not just one. Second, they were inclusive in the sense that the worship of one god did not detract from the worship of other gods. To exclude all other gods at the expense of one did not make sense. This is why some Romans incorporated Jesus so easily into their circles of deities. Third, paganism was not organized institutionally, doctrinally, or hierarchically. Ethical conduct still played an important role in people’s lives, but it was not theologically prescribed. Fourth, pagan religions were not centered on sacred writings. Since there were no scriptures to survive, our knowledge of these religions is limited.

3.4 The Influence of Greek Religion and Mythology

Fig. 3.5: Mosaic depicting Christ as Sol Invictus (“unconquered sun”), which was the sun god in the later empire, Helios, or Apollo. Vatican, 4th century CE.

Most people today in the Western world have some awareness of Greek mythology. They may have been taught some of the Greek myths in elementary school or were exposed to them in modern media. The old stories continue to emerge on occasion in literature and film, ranging from subtle influences, such as The Matrix (which is a rich amalgam of Christianity, Eastern religions, and Greek mythology) and O Brother, Where Art Thou? (which is based on Homer’s Odyssey), to full length reenactments, such as 300, Troy, and Clash of the Titans. While the ancient myths still speak to the biggest mystery of all—ourselves—they do so as metaphors and symbols for human characteristics in their portrayal of gods, such as passion, lust, love, jealousy, courage, hate, and anger. Some of the ancients understood the myths in the same way as we do today. But to many of the ancient Greeks and Romans, they played a more significant role in explaining why life unfolds in the way it does. Those who accepted these stories of the gods and their interaction with human beings as historical depictions, found in them their own identities, meanings, and fate. In addition to explaining the origins of life and the world, the myths brought comfort because they explained tragedy and suffering. An interesting feature about the Greek myths is that while the gods superseded humans in power, ability, intelligence, and immortality, they were not superior in morality.

Fig. 3.6: Relief of deities, Ephesus Museum, 4th century CE. The figures have been identified from left to right as (1) Dae Roma, (2) Selene, (3) a god, (4) Apollo. (5) Artemis, (6) Androclos and his dog, (7) Heracles, (8) Dionysus, (9) Hermes or Emperor Theodosius, (10) Hecate or Artemis of Ephesus, (11) Aphrodite or Cybele, or wife of Theodosius, (12) Ares, and (13) Athena.

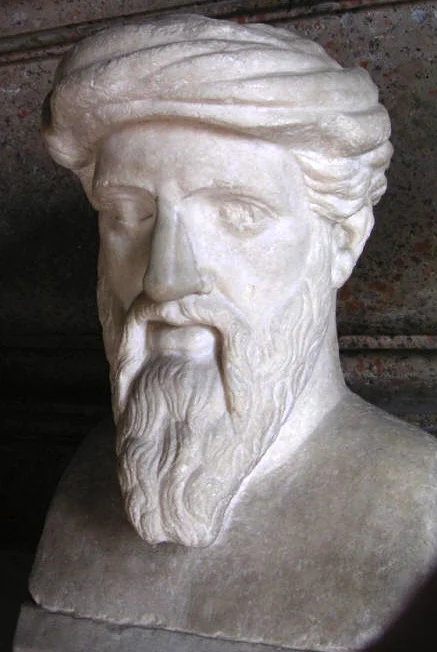

The structure of the gods in Greek, and later Roman, thinking was hierarchical, meaning that the “ruling gods,” like Zeus, Artemis, Aphrodite, and Poseidon were worshiped across the Mediterranean. Though not mentioned in the mythologies, it is possible that some Greek philosophers like Plato believed in one grand deity who supported the entire structure. Below the ruling gods were local deities and family gods who protected the welfare of the residents of villages and members of households. The family deity, called a genius, was worshiped through prayers and simple offerings like food or wine. Later among the Romans, many households contained shrines dedicated to this practice. In the hierarchical structure, family gods were one level above demigods, heroes, and immortals, who were an amalgam of gods and humans. Some were born of a divine father (usually Zeus) and a human mother, whereas others were given divine status posthumously—thus attaining the designation “son of a god.” They were glorified human beings who were given divine characteristics and extraordinary abilities. They included great political and military figures, like Alexander the Great, and philosophers, like Plato and Pythagoras, and “holy men” who performed miracles and taught with wisdom, like Apollonius of Tyana. During the Roman period this group was associated with emperors, like Augustus.

Fig. 3.7: Bust of Pythagoras of Samos (c. 580-500 BCE), Capitoline Museum, Rome.

It is important to make a distinction between “holy men” or divine philosophers, like Apollonius of Tyana and Pythagoras, and those who were only godlike, such as Plotinus. The “holy men” were believed to communicate divine qualities and wisdom to their mortal subjects because of their divine parentage; whereas the godlike figures were esteemed because their intellectual abilities transcended ordinary human beings, despite their human parentage.

3.4.1 Zeus

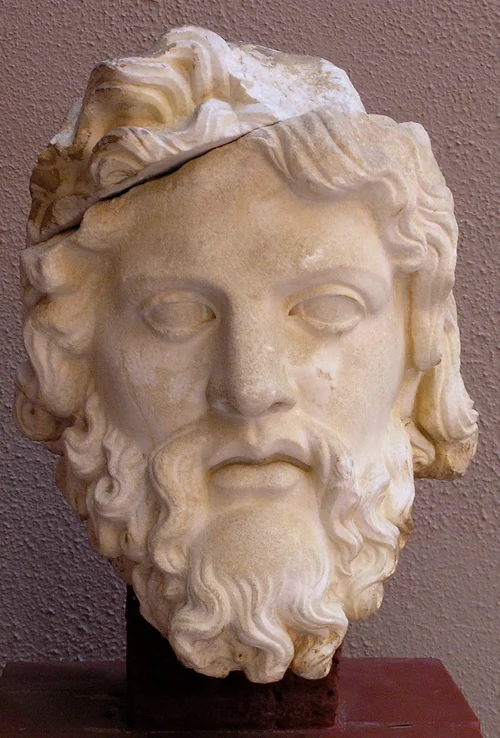

Fig. 3.8: Head of Zeus, Ephesus Museum, 1st century CE.

Two of the most popular gods, which continued to be revered in the first century, were Zeus and his son Apollo. Zeus ruled over the pantheon of gods by seizing control from his father Cronus, who had previously seized it from his father Uranus. The competition for power and control was a common practice among the gods. When Cronus’ children were born, he ate them for fear that they might eventually rebel against him. Zeus, however, narrowly escaped death with the help of his mother. When Zeus became an adult, he overthrew his father and liberated his siblings who were in their father’s stomach, among whom were Poseidon and Hades. The known world was divided up among the three with Zeus controlling the heavens, Poseidon the sea, and Hades the underworld. The gods had access to the earth from their capital in Greece, Mount Olympus.

3.4.2 Apollo

In the first century, the influence of Apollo was widespread across the Mediterranean. He was known as the god of poets, seers, and prophets. His temple at Delphi (Greece) was a popular destination because it housed the much-celebrated oracle. Thousands of devotees, including royalty, came from all over the Mediterranean basin to hear the oracle of Delphi prophesy about their destiny or fate. In the temple, which stood over a cavern, fumes seeped out and were thought to be the very breath of Apollo. These fumes caused the oracle, who was a priestess, to fall into a trance and mutter words which were recorded by priests and then interpreted to the inquirers.

Fig. 3.9: Temple of Apollo, Delphi. 4th century BCE.

3.5 Roman Religion

The Romans appropriated much of the Greek pantheon and many of the accompanying myths. Many of the gods, however, received different names. For example, Zeus was given the name Jupiter, Aphrodite became Venus, and Poseidon was known as Neptune. Greek temples were refurbished to house the renamed gods and rituals were altered to fit Roman ideals.

Fig. 3.10: The Temple of Antonino and Faustina (2nd century CE) was converted to a Christian church in the 7th century, when it was renamed San Lorenzo in Miranda. Rome.

The Romanization of the Greek gods and temples represented a practice that was common among new dominant powers. When Christianity became the religion of the empire, churches were built on the sites of pagan temples. Those temples that could not be easily destroyed were simply refurbished, often with a different façade. Images, customs, rituals, and other religious practices were reformulated to suit the new religion. One such reformulation of a pagan festival was the celebration of Christmas. Were it not for pagan winter solstice rituals, Christmas would not be celebrated when it is today, and maybe would not have been celebrated at all.

Fig. 3.11: Relief of the Ara Pacis Augustae (Altar of Augustan Peace) in a religious procession, depicting Augustus as the Pontifex Maximus and the members of his family. Uffizi Museum, Florence.

The Romans fundamentally believed that the success, peace, and prosperity of the empire depended on the pax deorum, the good will of the gods. In Rome, while senators occupied the highest political and military positions, they also played important roles in religious matters at the highest levels, including the priesthood. The Roman religious system was organized and led by priests (in conjunction with magistrates) who represented the gods. Organized into colleges, they oversaw the practice of public rituals, such as sacrifices, feasts, and festivals. The overall authority was the emperor, who came to be known as Pontifex Maximus, the chief priest of the empire. The title Pontiff was later applied by Christians to the Pope, the bishop of Rome. The emperor was believed to have enjoyed the favor of the gods, and was therefore regarded as the son of a god. His decisions and policies in the ruling of the empire were regarded as divinely willed, particularly by Jupiter, the king of the gods. The favor of the gods to the emperor was established long before they took office. Ancient biographies of the emperors sometimes include some kind of divine experience or relationship. Some of these included omens, signs, and even human and divine parentage.

One of the best examples of the connection between the gods and an emperor is the story of the birth of Augustus from Suetonius, Lives of the Caesars, Augustus 94.1-4:

1. Having reached this point, it will not be out of place to add an account of the omens which occurred before he was born, on the very day of his birth, and afterwards, from which it was possible to anticipate and perceive his future greatness and uninterrupted good fortune.

2. In ancient days, when a part of the wall of Velitrae had been struck by lightning, the prediction was made that a citizen of that town would one day rule the world. Through their confidence in this the people of Velitrae had at once made war on the Roman people and fought with them many times after that almost to their utter destruction; but at last long afterward the event proved that the omen had foretold the rule of Augustus.

3. According to Julius Marathus, a few months before Augustus was born a portent was generally observed at Rome, which gave warning that nature was pregnant with a king for the Roman people; thereupon the senate in consternation decreed that no male child born that year should be reared; but those whose wives were with child saw to it that the decree was not filed in the treasury, since each one appropriated the prediction to his own family.

4. I have read the following story in the books of Asclepias of Mendes entitled Theologumena. When Atia had come in the middle of the night to the solemn service of Apollo, she had her litter set down in the temple and fell asleep, while the rest of the matrons also slept. in a sudden moment, a serpent glided up to her and shortly went away. When she awoke, she purified herself, as if after the embraces of her husband, and at once there appeared on her body a mark in colors like a serpent, and she could never get rid of it; so that presently she ceased ever to go to the public baths. In the tenth month after that Augustus was born and was therefore regarded as the son of Apollo. Atia too, before she gave him birth, dreamed that her vitals were borne up to the stars and spread over the whole extent of land and sea, while Octavius dreamed that the sun rose from Atia’s womb.

3.5.1 Emperor Worship

Fig. 3.12: Denarius depicting Augustus as a son of a god (perhaps as Neptune) resting his foot on the world. 27 BCE. Notice that the world is represented as a globe, which is contrary to belief that the earth came to be viewed as a sphere during the time of Christopher Columbus.

Honor and reverence of an emperor’s divine sanction, known as the Imperial Cult, was celebrated throughout the empire. People would usually come to designated places that housed the image of the emperor and paid reverence and homage through various rituals, like offerings of food, sacrifices of animals, and prayers. Ascription of divinity to emperors was inconsistent. Some, like Augustus, were made divine posthumously, whereas others were not considered divine at all. Although the meaning of the cult is disputed, it is agreed that participation in it conveyed loyalty, which was essential in maintaining a unified empire. Most of the funding for the cultic practices throughout the provinces came from the elite, who benefited financially from a stable, unified, and peaceful empire. Participation in the cult was not compulsory, but was encouraged by the elite and the Roman provincial authorities. Broad participation not only elevated the prestige of the elite, but also added significantly to the local economies, such as the purchase of sacrificial animals. Practice of the Imperial Cult spanned across the provinces from the reign of Augustus onward, but it was not uniform. For instance, in some places offerings and prayers were given to the emperor’s image, whereas in other places, like the Jerusalem Temple, they were offered for the emperor himself.

Fig. 3.13: Temple of Hadrian, Ephesus, 117 CE.

By the time of the Flavian emperors (which began with Vespasian in 69 CE), the cult was widespread throughout the empire. Eventually, some provinces developed centralized structures, namely temples, for broader provincial gatherings, festivals, and sacrifices. For example, the temple at Ephesus was a central location of worshipers across Asia. Emperor worship played an influential role in early Christianity. As was discussed in the first chapter, the emperor was not only regarded as the king of the Roman kingdom, so to speak, and “son of a god,” but he was also viewed as “savior,” “ the bringer of the good news of peace,” and the “divine one.” Peace and prosperity were credited to the emperor and his family’s genius.

Excerpts from two inscriptions convey this honor. The first inscription is in honor of the emperor Augustus, dated to 9 BCE, from Priene, Asia Minor.

The providence which has ordered the whole of our life, showing concern and zeal, has ordered the most perfect consummation for human life by giving it to Augustus, by filling him with virtue for doing the work of a benefactor among men, and by sending in him, as it were, a savior for us and those who come after us, to make war to cease, to create order everywhere...; the birthday of the god [Augustus] was the beginning for the world of the good news [gospel] that have come to men through him...

The second inscription, dated to 38 CE, was commissioned by the city of Ephesus in honor of the emperor Caligula (Gaius Julius Caesar Germanicus).

The council and the people of Ephesus and other Greek cities, which dwell in Asia and the nations acknowledge Gaius Julius, the son of Gaius Caesar, as High Priest and absolute ruler, … the god visible who is born of (the gods) Ares and Aphrodite, the shared savior of human life.

For the early Christians, such titles and attributions belonged only to Jesus, who was the king of the kingdom of God, which trumped the kingdom of Rome. Many scholars have argued in recent years that early Christian preaching and the titles attributed to Jesus in the New Testament should be viewed as direct challenges to the Imperial religious and political system.

3.5.2 Superstition

Fig. 3.14: Mosaic depicting supersitious charms that ward off the evil eye. One of the most common charms worn by soldiers and boys was phallus (called a Fascinum), which represented Fascinus, the Roman god of fertility and abundance. Antioch, 2nd century CE.

Greco-Roman society was very superstitious, as might already be implied given Rome’s dependency on the pax deorum. Every possible communal and individual outcome, ranging from tragedies to victories, was explained through what we call superstitions, though not so called in the ancient world. The spiritual world with its forces and entities were inseparably intertwined with the physical world. When the state and families were healthy and prosperous, it was generally believed that religious practices were working because the gods were pleased. When the opposite was the case, it was believed that the gods were somehow angry. Sociologists have referred to this perspective as “enchanted” since causes and effects were explained by unseen forces as opposed to modern scientific explanations (such as those given by bacteriology, genetics, seismology, or neurosciences). By contrast, meaning, understanding, and explanation always incorporated the superstitious, such as the use of magical formulas; consultation of horoscopes and oracles; augury or prediction of the future by observing the flight of birds, the movement of oil on water, the pattern of entrails, the markings on a liver, or the hiring of professional exorcists (experts at casting out demons, of whom Jews were primarily sought). Only specially trained priests could practice these peculiar rituals and interpreted their meanings.

Consider this exorcism text:

For those possessed by demons, an approved charm by Pibechis: Take oil made from unripe olives, together with the plant mastigia and lotus pith, and boil it with marjoram (very colorless), saying, “Joel, Ossarthiomi, Emori, Theochipsoith, Sithemeoch [there follow further nonsensical tongue-twisters].… Come out of so-and-so.” But write this phylactery on a little sheet of tin, “Jaeo, Abraothioch, Phtha …,” and hang it around the sufferer. It is for every demon a thing to be trembled at, which he fears. Standing opposite, adjure him. The adjuration is this: “I adjure you by the god of the Hebrews Jesu, Jaba, Jae, Abraoth, Aia.… Let your angel descend … and draw into captivity the demon.…” But when you are adjuring, blow, sending your breath from above [to the feet] and [bouncing back] from the feet to the face, and he [the demon] will be drawn into captivity. Be pure and keep it [the formula] secret (Excerpts from the Paris Magical Papyrus).

Astrological signs were also popular.

Jupiter in triangular relation to Mars or in conjunction makes great kingdoms and empires. Venus in conjunction with Mars causes fornications and adulteries.… If Mars appears in triangular relation to Jupiter and Saturn, this causes great happiness, and a man will make great acquisitions (Tebtunis Papyrus 276).

3.5.3 Syncretism

Fig. 3.15: Temple of Athena, Delphi, 4th century BCE.

Since most people throughout the empire were polytheistic, inclusive, and generally tolerant of religions, they tended to merge beliefs and practices. This merging is called syncretism. New gods could be imported and existing ones could be exported throughout the provinces. Some gods were linked with different places, groups, and functions, and other gods had powers that were divided among the temples. The gods were interested and involved in the lives of people, but not always with good intentions. The gods were fickle, and so were their devotees. Changing allegiance from one god to another was common practice. The choice was often pragmatic. When one god seemed to be absent and did not perform as requested, another was petitioned. In contrast to the monotheism of Judaism and Christianity, it was an incoherent and often arbitrary practice. There were no sacred texts, but throughout the provinces there were shrines, temples, and sacred places, like Delphi, which were associated with divine revelation and experience. Often the Greco-Roman myths played a role in the popularity and preservation of such sites.

Syncretism was also operative in some sectors of Christianity. Surviving Christian art discovered on walls in catacombs from the second century depict Jesus as a Roman magician or perhaps a Roman god. Jesus wears a toga, is clean-shaven, and sports a wand. One such depiction has Jesus raising Lazarus from the dead.

Fig. 3.16: Fresco of Jesus with a wand raising Lazarus, Catacomb of Giordani, Rome, 3rd century CE.

In the provinces, a number of cities were associated with certain deities. To reject them, was in effect to reject the traditional power structures and an affiliation with the community’s identity. When Christianity eventually departed from its Jewish roots, it was quickly regarded as suspect because it was no longer considered old. Despite paganism’s tolerance and inclusivity, it still valued older religions above and beyond new ones. The age of the religion corresponded quite often to its legitimacy. This may be one of the reasons why the New Testament writers quote so often from the Jewish scriptures. Christians may have wanted to demonstrate to their pagan neighbors that their new faith is the fulfillment of Judaism.

3.6 Mystery Religions

Fig. 3.17: Fresco from the Villa of Mysteries, Pompeii, 1st century. This scene is commonly interpreted as an initiation ceremony into the Dionysian mystery cult.

Several forms of pagan religions have been classified as mystery religions or mystery cults because membership in these associations required secret initiations. Experiences that resulted through ritual practices were secretive. Divulgence of the secrets led to expulsion. Not much is known about these groups, but we do know that they practiced rituals involving ceremonial washing, blood sprinkling, sacramental meals, intoxication, emotional frenzy, and sexual activity that was believed to unite them with deities.

Many of their practices and beliefs were centered in myths about the death and resurrection of gods. Several of these stories speak about goddesses whose lovers or children died and were later brought back to life. Anthropologists have often proposed that the theme is rooted in agrarian cultures that celebrated the seasonal growth cycle from death in winter to life in spring. Consequently, the devotees were likewise promised purification, fertility, and immortality of the soul after the death of the body. Devotion to one’s god of choice was believed to result in a blissful post-death existence.

Initiation practices were abundant. Here is an excerpt from the second century Latin novelist Lucius Apuleius,

About midnight I saw the sun shine brightly. I likewise saw the gods celestial and the gods infernal, before whom I presented myself and worshiped them.… When morning came and the solemnities were finished, I came forth sanctified with twelve stoles and in a religious habit.… In my right hand I carried a lighted torch, and on my head was a garland of flowers with white palm-leaves sprouting out on every side like rays. Thus I was adorned like the sun (Metamorphoses or The Golden Ass 11.23–24).

Fig. 3.18: One of the most common representations of the Mithraic mysteries that has survived is the slaying of the sacred bull by the god Mithras who comes down from heaven to perform a sacrificial act. The bull’s blood appears to be desired by the other creatures. Vatican Museum, Rome, 2nd century CE.

Mystery religions were widespread and attractive in the ancient Mediterranean world. Archeologists have found evidence of religious practices in Egypt, Asia, Mesopotamia, and Rome. Though they had common characteristics, they were not all the same. They varied from region to region, employing different practices. They were known by various names associated with either their chosen deities, such as Mithras, Isis, Dionysus, and Cybele, or their location, such as the Greek town of Eleusis. In contrast to broader paganism, it was common for a devotee of the mystery cults to have chosen one deity for life—a personal god and savior as such. Unlike the public religions, which tended to concentrate on communal prosperity (e.g. the state, village, family), the mystery cults tended to focus on the well being of the individual.

While there is broad agreement that these cults existed in the first century, most of our information about them ranges from the fourth to the second centuries. The New Testament writers do not explicitly interact with the mystery cults, but there is no question that they were familiar with them, especially missionaries like Paul. Since many of the themes and characteristics of the mystery cults are closer to second century Christianity than they are to other pagan religions, some scholars have wondered about possible connections and influences.

About a century ago, as Greco-Roman archaeology was flourishing, scholars were intrigued how early Christianity resembled the mystery cults. Both were secretive societies that required initiation and instruction for membership. Both groups worshiped a single deity. Both focused on the death and new life of their chosen deity. Both practiced a few similar rituals, especially associated with wine as a symbol for blood. Both had an individualistic quality. And both promised a blissful post-mortem existence for faithful devotees.

Fig. 3.19: Mosaic of the personification of Soteria (Salvation), the goddess of deliverance and safety. Hatay Archaeological Museum, Antakya, 5th century CE.

Modern scholars, however, are less inclined to view early Christianity as a mystery cult because the differences are too great. Nevertheless, the parallels are intriguing and their explanations have not been exhausted. It must be remembered that although we have some information on the mystery religions, it is less than desirable. Much more work is still to be done on possible lines of connection.

3.7 Gnosticism

The Greek philosopher Plato (d. 348/347 BCE) is well known for proposing a dualistic contrast between the invisible world of ideas and the visible world of matter. The invisible world was superior because it contained the true ideals and forms of things, whereas the visible world only contained copies. Thus the invisible world is the real and unchanging world. The visible world is only an image and always changing. Think, for example, of a chair. For Plato, the true (or perfect) chair or idea of “chairness” only resides in the invisible world of ideas. Every physical chair in the world is only an imperfect copy. This dualism formed the foundation of Gnosticism, which began to take shape in the late first century CE. In general, the Gnostic system was influenced by Plato’s dualism in the sense that matter was equated with evil, and spirit (or the immaterial) was equated with good. Out of this basic dualism emerged two general schools of thought: (1) asceticism, which suppressed all physical passions since everything associated with the body was considered evil, and (2) libertinism (or sensualism), which indulged in all sorts of bodily passions because they were irrelevant in the pursuit of true spirituality.

Fig. 3.20: Fresco of Socrates, Ephesus Museum, 1st century CE. This is one of only a few portraits of Socrates in existence that has survived.

The goal of Gnosticism was spiritual immortality as opposed to physical eternal life. Gnostic salvation was achieved through the attainment of secret doctrines and passwords, which were used by departing souls on their way to heaven. Knowledge (which in Greek is gnosis, and the root of Gnostic) of the secret doctrines and passwords made it possible for the soul to elude hostile demonic guardians of the planets and stars as it journeyed from earth to heaven. In this system, the human problem is not guilt, which is remedied by forgiveness, but rather ignorance, which is remedied by knowledge. This idea is encapsulated in line 3 from the Gospel of Thomas: “When you know yourselves, then you will be known; and you will know that you are the sons of the living Father.” The relationship between Gnosticism and Christianity has been hotly debated and is discussed in the next chapter.

The Mystery Religions and Gnosticism were unusual in comparison to the many expressions of paganism because they advocated a blissful existence in the afterlife. Unlike most people of faith today who are motivated by the hope of heaven and by the fear of hell, the average pagan in Roman society had no such aspirations of an eternal bliss or fear of an eternal punishment. Notions of the afterlife were generally undeveloped. People had a vague sense of life going on after death, but it was a nebulous existence that was not particularly attractive. Rewards and punishments were associated with the present life, much like the blessings and cursings of God are meted out on Israel in the Pentateuch. Religion was therefore not practiced for the purpose of some celestial reward; rather, it was practiced for the purpose of managing the anxieties of daily life.

3.8 Philosophies

In the ancient Mediterranean world, philosophy and philosophizing played a prominent role in the intellectual and entertainment life of the elite, who had considerable time at their disposal. Intellectuals sought purer forms of thought in their ultimate quests for truth. Unlike the popular practices of paganism where ethics and doctrines meant very little and the appeasement of the gods meant everything, philosophers were concerned with moral conduct and the meaning of justice, good, evil, love, and happiness. Although religion and philosophy overlapped, their ultimate foci differed. Philosophers, for example, engaged in religious discussions about the providence of the gods – but on a critical level.

Fig. 3.21: Raphael’s “St. Paul Preaching in Athens.” 1515. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

In advanced formal education, two common fields of study were philosophy and rhetoric, the art of persuasion. The Apostle Paul was undoubtedly a student of both. He uses rhetorical strategies throughout his writings and is described by Luke as being familiar with Greek poets and philosophers (Acts 17:28). When Paul addresses the Stoic and Epicurean philosophers in Athens, he cites a popular poem attributed to Epimenides of Crete that honors Zeus (“in him we live and move and have our being”) as well as a popular saying from the Phaenomena of Aratus, a fellow Cilician (“For we too are his offspring”).

Fig. 3.22: The Areopagus (Ares Rock), where Paul delivered his sermon to the philosophers, was the site of a court in Classical Athens. The Romans renamed it “Mars Hill” after their god of war. Today, only a large rock remains.

There were various philosophical schools, but the most relevant ones for New Testament studies were the Epicureans, who were founded on the teachings of Epicurus (341-270 BCE) and the Stoics, who were founded on the teachings of Zeno of Citium (333-262 BCE). The name “stoic” was derived from the stoa poikile (“painted porch”) where Zeno taught. The latter philosophy was far more popular among the elite during the Roman period. Both schools of thought had an old and rich tradition. Both also placed great importance on the use of reason. As with all the philosophical schools, they were concerned with the good and what constituted the peaceful and happy life. While their goals were the same, their means differed significantly. For the Epicureans, the happy life was achieved through pleasure, though not necessarily of a sensual kind. It was a pleasure of a simple kind that could be attained on a daily basis through the exercise of all senses and especially the mind. Among the chief pleasures, for example, was friendship. They elevated free will and the human ability to achieve the good life. In the process, they denounced divine manipulation of human affairs. Their philosophy comes close to modern day materialism and empiricism. One of the best summaries of Epicureanism is found in the poem On the Nature of Things by Lucretius (99-55 BCE).

Fig. 3.23: Bust of Zeno of Citium (c. 334-262). Naples Archaeological Museum, 3rd century BCE.

Stoicism, on the other hand, taught that every person should accept one’s fate, as determined by an impersonal divine reason (known as God or Nature) that governs the natural order, of which all humans are a part. Since all life emanates from the one universal spirit, humanity was viewed as the manifestation of God. In contrast to the Epicurean principle of free will, the Stoics advocated a determinism that was too pervasive in the universe to ignore. The ethical focus of Stoicism was the development of self-control and the mastery of destructive emotions (such as anger, envy, and jealousy) that can interfere with reason. The good life was the virtuous life, which meant the freeing of oneself from anxiety and suffering through peace of mind and clarity of judgment. The four staple virtues of Stoicism, as originally taught by Plato, were wisdom, courage, justice, and temperance.

Fig. 3.24: Bust of Emperor Marcus Aurelius, Ephesus Museum, 2nd century CE.

Despite Stoicism’s pantheistic core, it was similar in some respects to early Christianity. In addition to the adoption of certain terms, like logos (Word), “spirit,” and “virtue,” early Christians shared certain ideas with the Stoics, such as the belief in human frailty and depravity, the inadequacy and temporality of material possessions, the problem of physical and emotional passions, and the need to awaken and unite with the divine. One of the best representations of Stoic philosophy and spirituality—and prized by many Christians throughout history—is the Meditations by the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius (121-180 CE).

Consider a few examples from the following Stoic texts:

The General Law, which is Right Reason, pervading everything, is the same as Zeus, the Supreme Head of the universe (Zeno, Fragments 162).

He is free who lives as he wishes … whose choices are unhampered, who gets what he wants to get and avoids what he wants to avoid (Epictetus, Discourses 4.1.1).

The soul of man does violence to itself, first of all, when it becomes an abscess and, as it were, a tumour on the universe, so far as it can. For to be vexed at anything which happens is a separation of ourselves from nature, in some part of which the natures of all other things are contained. In the next place, the soul does violence to itself when it turns away from any man, or even moves towards him with the intention of injuring, such as are the souls of those who are angry. In the third place, the soul does violence to itself when it is overpowered by pleasure or by pain. Fourthly, when it plays a part, and does or says anything insincerely and untruly. Fifthly, when it allows any act of its own and any movement to be without an aim, and does anything thoughtlessly and without considering what it is, it being right that even the smallest things be done with reference to an end; and the end of rational animals is to follow the reason and the law of the most ancient city and polity (Marcus Aurelius, Meditations 2).

The Stoics say that when the planets return … to the same relative positions … they had at the beginning …, this produces the conflagration and destruction of everything that exists. Then the world is restored anew in a precisely similar arrangement as before. The stars move again … without any variation. Socrates and Plato and each individual human being will live again with the same friends and fellow citizens. They will go through the same experiences and the same activities … over and over again—indeed to eternity without end.… For there will never be any new thing … but everything is repeated down to the minutest detail (Chrysippus, Fragments 625).

Try the Quiz

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Barrett, C. K. The New Testament Background: Selected Documents. 2d edn. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1989.

Cotter, W. Miracles in Greco-Roman Antiquity: A Sourcebook for the Study of New Testament Miracle Stories. New York: Routledge, 1999.

Lane, E. and R. MacMullen, eds. Paganism and Christianity: 100-425 C.E.: A Sourcebook. Philadelphia: Fortress, 1992.

Meyer, M., ed. The Ancient Mysteries: A Sourcebook. San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1987.

Robinson, J. M. et al. The Nag Hammadi Library in English. 2d edn. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1990.

Shelton, J. –A., ed. As the Romans Did. A Source Book in Roman Social History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Secondary Sources

Casson, L. Everyday life In Ancient Rome. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

Cohn-Sherbock, D. and J. M. Court, eds. Religious Diversity in the Graeco-Roman World: A Survey of Recent Scholarship. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001.

Crossan, J. D. and J. L. Reed. In Search of Paul: How Jesus’s Apostle Opposed Rome’s Empire with God’s Kingdom. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 2004.

Foerster, W. Gnosis. 2 vols. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972–74.

Goodman, M. Rome and Jerusalem: The Clash of Ancient Civilizations. London: Penguin, 2007.

Horsley, Richard A., ed. Paul and Power in Roman Imperial Society. Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press International, 1997.

Howatson, M. C. ed. Oxford Companion to Classical Literature. 2nd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Klauck, H.-J. The Religious Context of Early Christianity. A Guide to Graeco-Roman Religions. Studies of the New Testament and its World. Translated by B. McNeil. Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 2000.

MacMullen, R. Paganism in the Roman Empire. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981.

Martin, L. H. Hellenistic Religions: An Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

Price, S. R. F. Rituals and Power: The Roman Imperial Cult in Asia Minor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Rudolph, K. Gnosis. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1987.

Turcan, R. The Cults of the Roman Empire. Oxford: Blackwell, 1996.