Module Six

The New Testament Manuscripts

6.1 Introduction

Fig. 6.1: 10th century illumination of Mark writing his Gospel. Strahov Monastery, Prague.

It is common knowledge today that English translations of the New Testament are based on a Greek text. But where does that Greek text come from? Do we have the original manuscripts (i.e. hand written texts) of the New Testament writers hidden somewhere in a museum vault? Do we only have copies of the original manuscripts? If so, how far removed are they from the originals, and how accurate are these copies? In this chapter, we will explore these and related questions about the New Testament manuscript evidence, history, and accuracy. This is the field known as textual criticism. The general task of the textual (or text) critic is to gather, identify, and evaluate manuscript copies that have come down to us throughout history with the ultimate aim of reproducing the original work as best as possible. The final product is usually a “critical edition,” which contains the reconstructed original text along with references to manuscripts that agree and disagree with the reconstructed reading.

Unfortunately, we do not have the original manuscripts or autographs of the New Testament writings. What we do have are numerous manuscript copies written over approximately 1400 years. Before the first formal printing of the Greek New Testament in 1516, the New Testament writings circulated as hand written copies throughout the Christian world. Before the printing press, all documents were copied by hand and were much more susceptible to common challenges associated with copying.

Fig. 6.2: This is the first page of Matthew in the NA 27. The bottom of the page indicates variant readings. Every page of the New Testament is much like this one.

The first printed edition of the Greek text in 1516 was a remarkable attempt at reconstructing the original. Since then the science of textual criticism has advanced in leaps and bounds, and is today being advanced even further with the aid of computer and digital technology. In addition, we have discovered many more manuscripts, allowing for even greater accuracy in the reconstruction process. The main critical edition of the Greek New Testament is Nestle-Aland – Novum Testamentum Graece, 27thedition (cited as NA 27).

6.2 How Were Manuscripts Produced and Distributed?

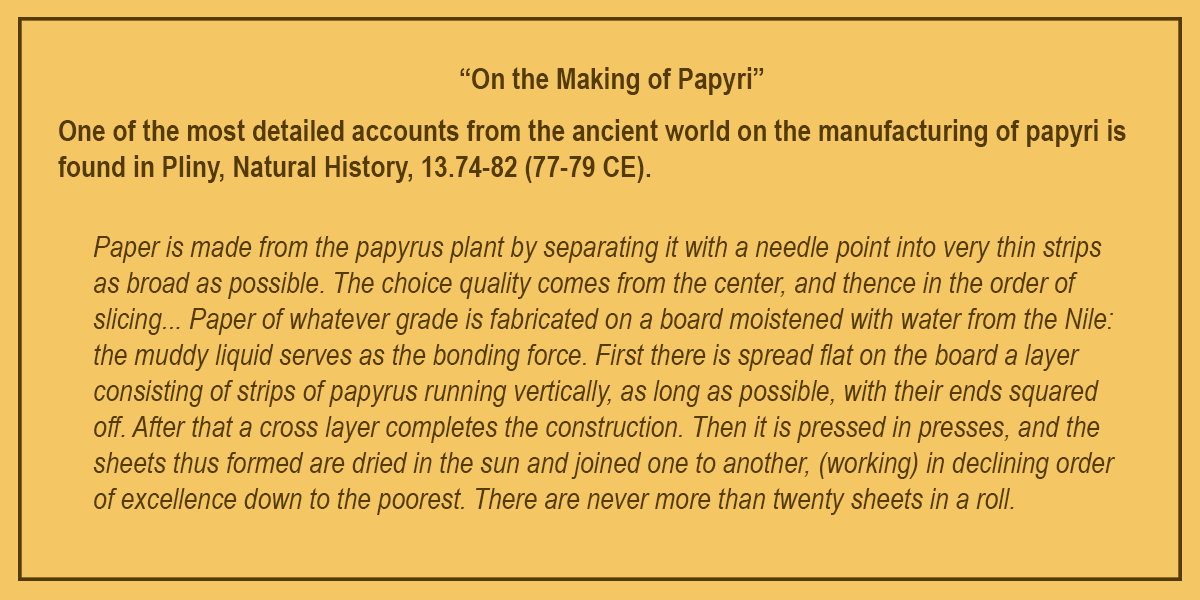

6.2.1 Papyri

Fig. 6.3: Papyrus plant

Most of the manuscripts of the New Testament, including the autographs, would have been written on material made out of the plant called papyrus, which was plentiful in the Nile River basin. By the first century, papyrus manufacturing was already well established, going back to the third millennium BCE. The papyrus plant was usually found and cultivated along the shoreline of the Nile. Fifteen-foot stalks of papyri were cut down. The outer rind was removed. Then the inner, sticky material was cut into sixteen-inch strips, which were laid alongside each other, slightly overlapping at the edges. While still damp and sticky, another layer at right angles was pressed onto the first layer, and left to dry. The formed sheets were flattened under pressure, and then were finally trimmed.

The writing instruments were made of reeds that were flattened or chewed at one end to create a brush effect. The ink was made out of a mixture of carbon soot, resin, wine dregs, and cuttlefish ink. Later in the second century, a brownish ink, made of iron and tanning compounds, was also used, but mainly on parchment, which is a very fine grade of treated sheep or goat leather.

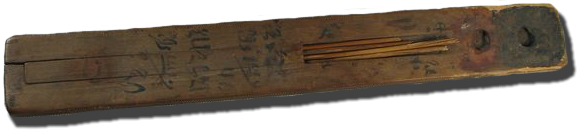

Fig. 6.4: Writing instruments made from papyrus stalks.

Fig. 6.5: Scribe’s palette with writing instruments.

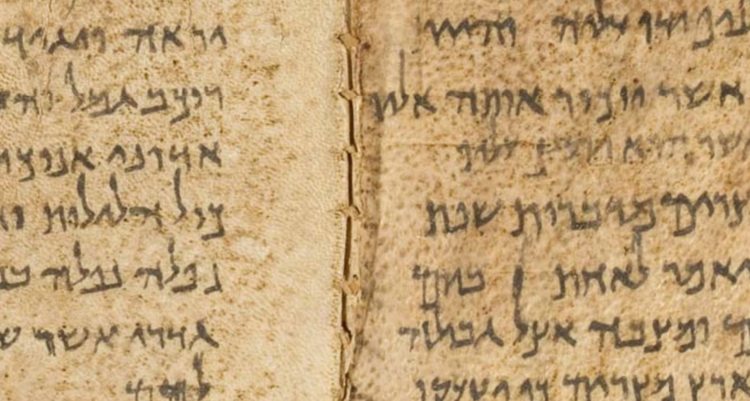

6.2.2 Scrolls

Fig. 6.6: Stitching on the Great Isaiah Scroll.

When most people today think of scrolls, they think of synagogue readings. But in most Jewish temples or synagogues around the world, the scroll has become a symbol for the scriptures. Bible readings are usually taken from books. The mention of the term “scrolls” today can also imply that one is referring to the famous discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls. This certainly is the case among academics who study sacred texts. The most preserved texts among the Dead Sea Scrolls, such as the Great Isaiah scroll, was not written on papyrus, but on treated calf leather called vellum.

Fig. 6.7: A Torah scroll.

In the ancient Mediterranean world, the making of scrolls (Lat, volumen) out of papyri was well known, but not affordable for the average person. They were expensive. In the manufacturing process, papyri sheets were laid side-by-side, overlapping on the edges. These were glued, left to dry, and then rolled up. Sheets with horizontal fibers were usually always on the inside, which allowed for easy writing. The text was then written in columns. Scrolls came in various lengths, but most were probably no longer than five meters, which corresponds to Pliny’s observation that twenty sheets were used per roll (Natural History, 13.74-82). There is some evidence that some scrolls came in lengths of ten meters or so. Though the famous Egyptian scroll called Papyrus Harris I is an astonishing forty-one meters, but it is dated to approximately 1150 BCE, and thus far removed from our present context. Scrolls allowed for longer life of the papyrus because they had the advantage of being rolled in a continuous curve, which minimized stress, folds, and breakage. It has often been said that Luke-Acts was intended to be a single writing, but it had to be separated because a single scroll would not have accommodated the length. Luke, Acts, Matthew, and John would have each fit a ten meter scroll.

6.2.3 Codices

Papyrus sheets could also be purchased individually. The most common dimensions of a sheet were ten inches by seven and a half inches. They were commonly used for writing letters, receipts, and various record keeping. Usually both sides were used. The horizontal side that followed the fibers, is called the recto side, and the back part of the page is called the verso side. At some point individual sheets began to be bound together. It was probably during the first century CE, though this is debated. One of the earliest examples of binding is represented in a wall painting from Pompeii of a young woman holding a tablet with four sheets of papyri. Over time, these bound sheets came to be called codices, or a codex in the singular, meaning “book.” The idea may have emerged from the use of wooden tablets as writing platforms. When the scribe used several sheets of papyri, he may have bound them to the tablet.

Some have even suggested that the early Christians played a significant role in the transition from scroll to codex. In order to differentiate from Jewish and pagan writings, the early Christians started to bind their works together. The reasons are unknown, though it is plausible that as certain Christian writings started to circulate around the empire, like Paul’s letters and the gospels, they needed to be kept in tact, not allowing for “outside” infiltration, and conversely not allowing for the removal of any writings in the collections.

Fig. 6.8: Wall painting from Pompeii showing a young woman holding a tablet with four sheets.

Later, in the manufacturing of codices, papyri sheets were cut into smaller “pages” and then glued or sown together one on top of the other to make a codex. The new technology caught on, and eventually became the predominant way writings circulated. Codices were less cumbersome than scrolls. They were easier to handle and more convenient to transport. When the New Testament writings began to be copied and re-copied over the next eight hundred years, they took the form of codices using papyrus pages.

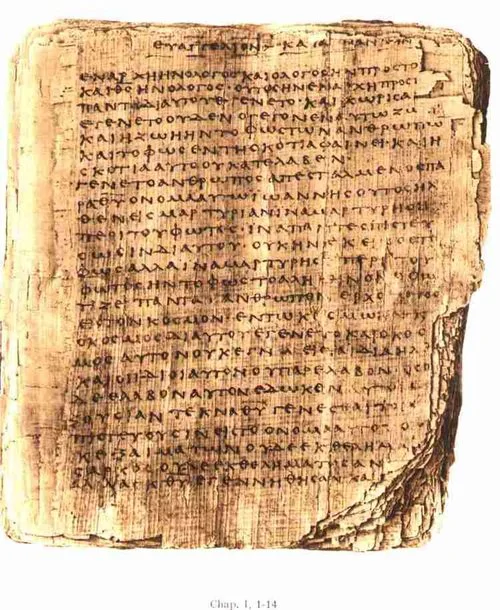

Fig. 6.9: P66. Pictured here is the beginning of John’s Gospel.

One of the drawbacks of using these early codices was their susceptibility to stress. Many of the New Testament papyri manuscripts that have been discovered survive only as single pages. In a codex the weakest point is the spine. Over time, pages broke away and were susceptible to further wear and breakage. One example of breakage is the Bodmer II Papyrus (P66), which contains much of John’s gospel, but only as separate pages. It is usually dated to 200 CE.

For further online reading on the use of papyri in codices, see James Grout, ed. “Scroll and codex,” http://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_romana/scroll/scrollcodex.html

6.2.4 Amanuenses

Authors did not necessarily write the words onto the papyri themselves. Rather, they often dictated to a scribe or secretary called an amanuensis. These professional secretaries were far more skilled in writing, and even perhaps reading, than those who employed their services. They were much quicker and more efficient than even many literate people. Amanuenses (plural for amanuensis) also had the necessary supplies for writing, like pens, papyri, ink, and a tablet. The method of recording was not always the same. It ranged. At one end of the spectrum, authors required their amanuenses to record dictations verbatim, word-for-word. At the other end, authors gave their amanuenses freedom to record dictations or general ideas in their own words, allowing them to choose the vocabulary, grammar, and style.

We do not know how often amanuenses were used by the New Testament writers. We also don’t know how they were used. We do know that Paul used one in the writing of Romans since in 16:22 the amanuensis identifies himself: “I Tertius, who writes this letter, greet you in the Lord.” Since the letter is very long, compared to ancient standards, it was most likely dictated and recorded over several days, and maybe longer. Beyond this, we do not know how much liberty Paul gave to Tertius. Did he require a verbatim dictation? Did he give Tertius liberty to choose vocabulary, grammar, and style? Or was the situation somewhere in between? We also have no knowledge about Paul’s editing process.

Fig. 6.10: Portable Roman writing table and an iron stylus inlaid with copper.

Another example of the use of an amanuensis is found in 1 Pet 5:12, where the author acknowledges the service of a certain Silvanus, writing, “Through Silvanus, our faithful brother (for so I regard him), I have written to you briefly, exhorting and testifying that this is the true grace of God. Stand firm in it.” This second example constitutes a final greeting that was sometimes written in the author’s hand, clearly recognizable due to its different cursive style. The end of Galatians conveys this as well, as Paul writes, “See with what large letters I am writing to you with my own hand” (6:11). Recognizing the use of amanuenses in ancient letter writing has helped us to better understand why letters written by the same author have so many variances in style and vocabulary.

6.2.5 Copying

Hand copying and distribution of manuscripts was the only means by which written material could circulate. In most cases the initial copying of the New Testament writings occurred because of the popularity or authority of the author. But this was not the only reason for copying. The public reading of letters and other writings was a form of entertainment. In some cases it was the only “news” in town. Most often, however, copying was a means to communicate an important message to recipients. In some cases the author may have wanted the same letter sent to various recipients. Or the author may have requested that the recipient of the letter change the addressee and forward it to another community. This was probably the case with the letter to the Ephesians, which was also known as the letter to the Laodiceans. In Col 4:16 there is indication that a letter from the Laodiceans was already in circulation. Conversely, Paul (if he was the author) instructs the Colossians to send the letter he writes to them on to the Laodiceans. Paul writes, “And when this letter is read among you, have it also read in the church of the Laodiceans; and you, for your part read my letter that is coming from Laodicea.” In some cases, circulation would have required copying in order to change the addressee, personal greetings at the end of the letter, and perhaps a few specifics that were particular to the new recipients.

Fig. 6.11: Wall painting from Pompeii showing a woman with a wax tablet and stylus.

As amanuenses were used by some authors to compose their writings, so professional scribes were used by some communities to copy them. Along with the ability to write legibly in an organized manner, making the most efficient use of a papyrus, they were skilled in reading various styles of writing. Like amanuenses, they also possessed the necessary tools required to practice their craft. The copying process was not instantaneous. Depending on the length of the project, availability of supplies, and requests for different formats, scribes sometimes took weeks to complete an order. Of course, the longer the task, the more expensive was the service. In addition to the scribe’s labour, customers needed to also pay for supplies.

6.2.6 Distribution

The distribution of copies in the ancient world was akin to modern publishing, but it was more of a private process than we might imagine. Since the high cost of book production was prohibitive for most people, and since illiteracy was the norm, writing and distribution was often supported by patrons. On some occasions, the author may have paid for his book and then distributed it himself. This was publication on a small scale. One of the most common means of publicizing one’s written work was by reciting it in public gatherings. Limited copies were then made and formally dedicated to an important person who might sponsor further distribution. In the ancient world publication was more associated with the distribution of books among friends and acquaintances who were interested in literature. Such networks were usually associated with entertainment among the elite. Commercial book trade, like today, was not developed during the early years of the empire.

Unlike today, the line between what was considered published and what was simply a private circulation was blurry. Though in most cases, publications were usually dedicated to an important person or a patron. As such, there is no indication in most of the writings of the New Testament that they were intended to be “published,” and yet in a fairly short time, they traversed the empire. Luke and Acts may be the only exceptions. At the beginning of both documents, Luke includes a dedication to a certain Theophilus, following standard literary convention in publications during the Roman period. Unlike in the broader Greco-Roman world, the main reason for the distribution of writings that would later be in the New Testament was to advance the new religion. As congregations began to multiply all over the empire, the distribution of Christian texts soon followed.

The actual distribution of early Christian writings, especially letters, was also a private enterprise. With the lack of a national postal service, senders like Paul would have relied on entrusted associates or friends to deliver his letters. These couriers are occasionally mentioned by Paul (e.g. Rom 16:1; 1 Cor 16:10; Eph 6:21) and by other writers (e.g. 1 Pet 5:12; 1 Clement 65:1). Sometimes letters were sent through professional couriers, but the common practice among Christians was to entrust them to fellow Christians who were already traveling to respective locations.

6.3 What Kind of Sources do We Have for Reconstructing the New Testament?

One of the (nice) problems that modern textual critics have is the vast quantity of manuscripts that have survived. These are sometimes also called witnesses. There are far more surviving fragments and copies of the New Testament than any other writing from antiquity. Today text critics sift through some 5400 Greek manuscripts, which range from small scraps of papyri that contain only a few words to entire anthologies. These manuscripts date from the second century to the fifteenth, with the advent of the printing press. As is discussed in more detail below, we also have thousands of manuscripts that were translated into other languages, like Latin, Syriac, Armenian, Coptic, and others. In addition, textual critics also include the countless quotations of the New Testament that appear in the Church Fathers and other early Christian writings. When compared to other writings from antiquity, the New Testament manuscript evidence is staggering. Not only are the manuscripts much closer to the actual time of the autographs, but also their number is vastly greater. For example, the Roman historians Livy, Tacitus, and Suetonius have fewer than 300 surviving copies. Livy's earliest manuscript dates 300 years after its original. Tacitus and Suetonius have much fewer surviving manuscripts. In fact, we only have a single copy of the first six books of Tacitus’ Annuls. The earliest surviving manuscripts for both Tacitus and Suetonius are dated 900 years after their autographs.

The oldest sources of the New Testament that we possess are only in fragment form. They are simply small pieces of papyri containing a few words. To date, the earliest fragment that we have is called P52 (the “P” is an abbreviation of papyrus). This fragment has been dated from approximately 125-150 CE. On one side, it contains John 18:31-33, and on the reverse side it has John 18:37-38. Since P52 is dated so closely to the autograph, scholars have jested that the ink on the original gospel of John was still wet when P52 was copied. All of the manuscripts that have survived from the first three hundred years of the church are in the form of loose pages or fragments. There is no complete copy of the New Testament from this period. Though astonishingly, the dozen or so manuscripts that date to the second century contain 43% of the verses in the New Testament. After the fourth and fifth centuries, the manuscript evidence expands dramatically to even include complete versions of the New Testament.

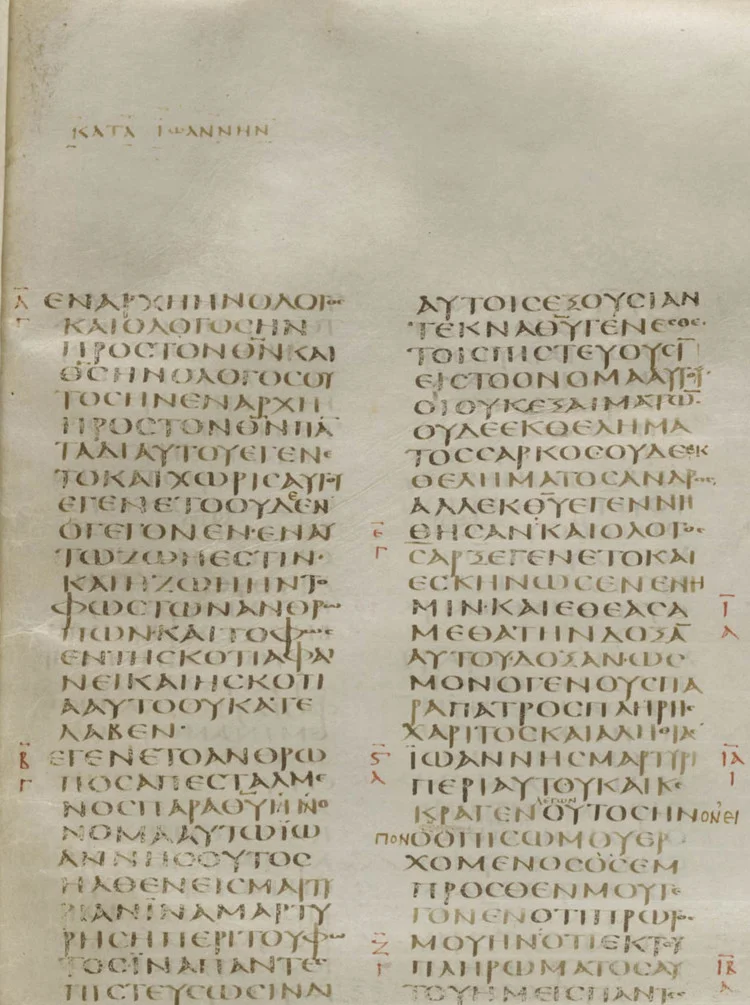

Fig. 6.12: Codex Sinaiticus. This is the beginning of John’s Gospel.

It was not until the nineteenth century that the first complete New Testament was found. In 1853, a German scholar named Constantin von Tischendorf returned to St. Catherine’s monastery at Mount Sinai after publishing some of the manuscripts that he had borrowed from the monks. When he returned the borrowed copies, a monk showed him a well-preserved and complete New Testament that would later be dated to the fourth century. What Tischendorf saw was the now famous Codex Sinaiticus. The monastery presented it to the Russian czar as a gift and it was later published in 1862. This is the earliest complete copy of the New Testament.

A standard way of organizing the vast number of witnesses is by classifying them into sources. There are three major classifications: Greek manuscripts, version of the New Testament, and Patristic (Church Father) quotations. Given the sheer volume of sources, we can only introduce the classification system here.

6.3.1 Greek Manuscripts

Fig. 6.13: Another large collection of papyrus sheets is P75 (also called Papyrus Bodmer XIV-XV), which contains the last half of Luke and the first half of John. It is dated between 175-225 CE. The figure is one of 102 pages that have survived. Pictured here is the ending of Luke and the beginning of John.

Papyri. The earliest extant witnesses are the papyri manuscripts. We possess 115 of these and they generally date to the fourth century CE. They are appropriately classified with a “P” and then a reference number (as above - P52). Their quality varies dramatically, from scraps that fit in the palm of one’s hand (e.g. P52) to collections of loose sheets. One of the large collections is P66, containing 104 pages from John’s gospel and dated to 200 CE.

Uncials. Although the term “uncial” refers to Greek script that is written in capital letters, it is also used to classify manuscripts dating from the fourth century to the tenth, written primarily on parchment. There are approximately 300 uncial manuscripts ranging from small fragments to the entire Bible. These are among the most dependable sources for reconstructing the original New Testament. Up until a hundred years ago Greek and English letters were used to identify individual manuscripts. The famous Codex Sinaiticus was even abbreviated with the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet, aleph ()), to bring attention to its significance. Today each uncial has a designated number that is preceded by a zero: for example, 01 Codex Sinaiticus, 02 Codex Alexandrinus, 03 Codex Vaticanus, and so on.

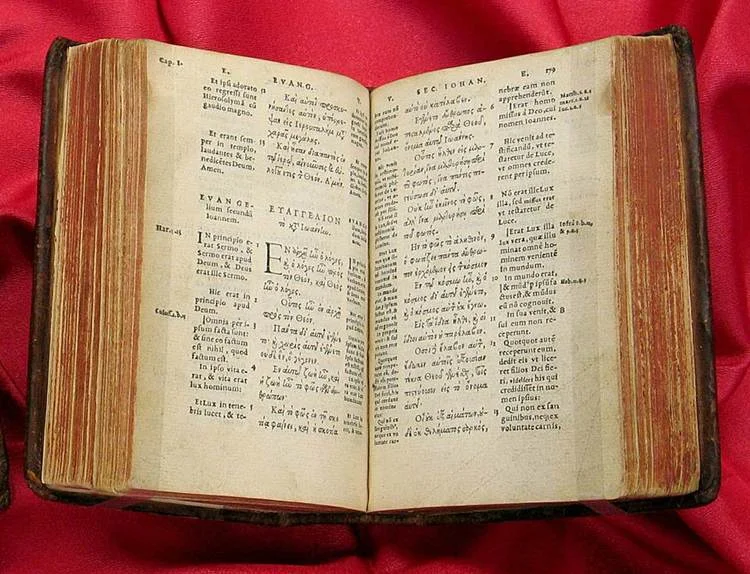

Minuscules. Named after their cursive (small case) script, this is by far the largest group of manuscripts, dating from the ninth century onwards. There are approximately 2800 miniscule manuscripts, written mostly on parchment, ranging from a few sheets to the whole New Testament. Modern designations are also numerical, preceded by “Cod.”: for example, Cod. 1, Cod. 2, and so on. The most well known miniscule is Codex 1, a twelfth century codex used by Erasmus to print the first Greek New Testament.

Fig. 6:14: This is the first edition of the Greek New Testament, with a Latin translation on the right, translated and edited by Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam (1466-1536). Published in four editions (from 1519-1535), it challenged the prevailing Latin translation by Jerome, and was used by Luther for his German translation.

Lectionaries. Lectionaries are structured church services that contain numerous quotations from scripture. Select scripture texts were chosen for both daily readings and for celebrations of special days in the church calendar, such as Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost. These readings were regarded as lessons for the laity. There are approximately 2000 lectionaries that contain New Testament quotations arranged according to the church calendar. Lectionaries contain the second largest group of New Testament witnesses. They range from the sixth century onward. Today, each lectionary has a designated number that is preceded by the letter “l” or the abbreviation “Lect.”

6.3.2 Versions

Translations in the ancient world were rare by our standards. The Greek translation of the Hebrew scriptures, known as the Septuagint (LXX), was therefore a monumental event. But as the Christian faith started to expand across the empire, the literature followed. The missionary agenda made translations more frequent. As new churches began to emerge in areas where Greek was not common, the need arose for translating the New Testament writings into the indigenous languages. In the ancient world, no other writings were translated as much.

There are eleven versions. Many have complicated histories and several branches of texts stemming from them. The versions are: Latin, Syriac, Coptic (Egyptian), Armenian, Georgian, Ethiopic, Gothic, Arabic, Persian, Slavonic, and Frankish.

Translations are, however, problematic when used as sources for reconstructing the original New Testament. One of the problems is that we do not have the original manuscripts of the versions. We have copies of copies. In a sense we are one step removed. Before a version can be used in the process of reconstructing the original text of the New Testament, textual critics must first ascertain what the original version looked like and on what Greek source it was based. A second problem is that there are inherent differences between languages. Latin, for example, does not have a definite article, whereas Greek does. Greek does not have a time-based verbal system. In addition, Greek is not as dependent on word order as other languages. Needless to say, using versions in the reconstruction process is a daunting task.

6.3.3 Patristic Quotations

Fig. 6.15: Icon of St. Irenaeus (c. 130-202), bishop of Lyon, holding the scriptures.

This final classification of sources focuses on the quotations of the New Testament in the Church Fathers up to approximately the sixth century. “Patristic” is an adjective derived from the Latin term pater, meaning “father.” There are so many quotations in the writings of the Church Fathers that one could reconstruct the entire New Testament from them without any other sources. Most of the quotations are in Greek and Latin, with a considerable number also in Syriac. Like the problems attending the use of versions, the use of quotations adds another step in the evaluation process. At least three main issues need to be considered when appealing to quotations. First, we do not know if a given quotation was changed when copied from its source. To compound the problem, since we do not have any autographs of the Church Fathers, we are not sure if the quotations were copied accurately. Second, we are not sure if any given quotation was intended to be recorded verbatim, as a paraphrase, or as a loose recollection of the New Testament. And third, we are not sure if some quotations were assimilations of parallel passages from the New Testament. This is called a conflation, and appears as early as the Gospel of Mark, where in the opening lines the quotation is attributed to Isaiah, but in actuality it is a conflation of verses form Exodus, Malachi, and Isaiah.

Nevertheless, the quotations in the writings of the Church Fathers can be of great value because they are early, their date and geographical location is usually known, and since a number of them wrote the first commentaries on the New Testament, they preserve entire Greek texts of individual New Testament writings.

6.4 How Does the Textual Critic Determine the Original Reading?

Textual Critics have a set of rules for evaluating the manuscripts. These rules guide their decisions for determining the most original reading of any given manuscript. Particularly important for the textual critic is how to deal with textual differences.

When we compare the entire collection of 5400 Greek manuscripts that span some fourteen centuries, we notice numerous differences, which are called variants. In fact, apart from a few small fragments, there is no manuscript that agrees 100 percent with another manuscript in wording. Granted that the vast majority of differences are slight, they tell us that scribes played a key role in making changes. Estimates range between 200,000 and 300,000 variants. Despite this staggering quantity, textual critics are convinced that the original New Testament writings can be reconstructed to almost 100 percent accuracy.

6.4.1 Six Types of Variants

Variants can be categorized into six types. Some of these may have been caused accidentally, whereas others may have been intentional. For an online introductory description of intentional and unintentional errors by scribes, with the aid of examples, see

http://legacy.earlham.edu/~seidti/iam/mss_trans.html

The first and most common variant is the spelling mistake. Although there was some standardization of spelling, it was not like today. Many spelling errors were certainly unintentional, but some could have been attempts at phonetic improvements by later scribes.

The next two are related. The second kind of variant is the omission. When manuscripts are compared with each other, and one or more are found to be missing a word(s), this is deemed a variant. Again, this may have been accidental or intentional. It would have been easy for an inattentive or tired scribe to omit a word or an entire line, especially if that line ended in the same way as the previous one. Take, for example, a very early copy of John 17:15, which omits a key line, illustrated by the square brackets: “I do not ask that you might take them from [the world, but that you might keep them from] the evil one.”

The third kind of variant is the addition. Conversely, when a manuscript is found to have an additional word(s) in comparison to other copies of the same passage, it is deemed a variant. The majority of omissions and additions are minor, spanning from a single word (usually words like “and” and “the”) to a single phrase. These number in the thousands. More significant are the omissions and/or additions of an entire verse or two. These occur twenty-four times. The longest variant of this type is the addition of twelve verses in both John 7:53-8:11 and Mark 16:9-20. These passages are often viewed as late additions, appended well after the original was written.

The fourth kind of variant is called a transposition, which is technical term for a change in word order. For example, one of the most common transpositions in the New Testament writings is the shift between “Jesus Christ” and “Christ Jesus.” In this example, there is no real shift in meaning, but rather in style. Sometimes a few letters are transposed, resulting in the writing of an entirely new word, which does affect meaning. One such example is the copying of John 5:39 in Codex Bezae from the sixth century. An accidental transposition of a few Greek letters changes the reading from “and they (the scriptures) are the ones that bear witness concerning me” to “and they (the scriptures) are the ones sinning concerning me.”

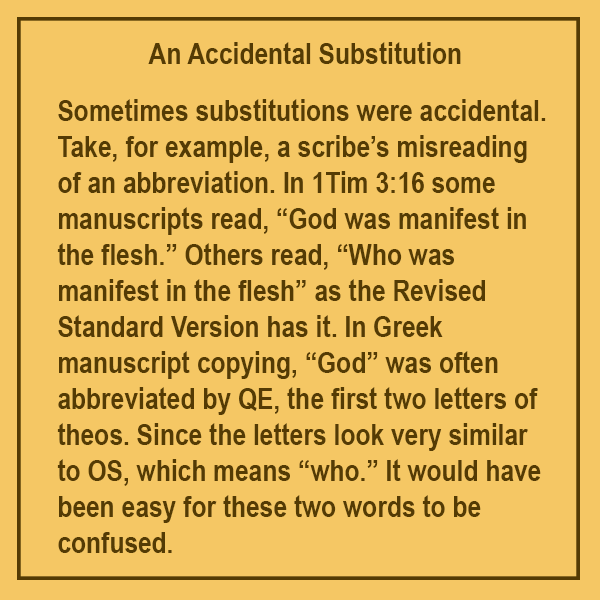

The fifth kind of variant is technically called a substitution. In this case, a word is intentionally replaced by another word. For example, the name “Jesus” is sometimes replaced by the title “Lord.” We also see the substitution of synonyms, such as “from” may be replaced by “out of.” In Greek such prepositions can affect meaning.

Finally, the sixth kind of variant is a complete alteration, which refers to a change in meaning from one manuscript to another. Scribes sometimes altered the phraseology in their new copy (over and against their source) in order to clarify a meaning that was perceived to be unclear. Sometimes a scribe wanted to harmonize passages that seemed at odds with one another. This is especially seen in copies of Matthew, Mark, and Luke. For example, the Lord’s Prayer in Luke 11:2-4 is harmonized with the longer version of the prayer in Matt 6:9-13. At times, it appears that the scribe’s alteration was motivated by theological reasons. In this case, the scribe made sure that the new copy would contain wording that was closer to his theology. This kind of variant does not occur often.

6.4.2 Criteria

In light of these variants, the textual critic must somehow determine which is the best representation of the original. So how does one proceed to do this? Although this is a complex undertaking, it can be filled with intrigue, much like the investigation of a murder mystery where evidence needs to be collected, evaluated, and then used to reconstruct the event. Textual critics also need to evaluate the evidence. They do this by subjecting the plethora of manuscripts to various tests or criteria. These criteria, or principles as they are sometimes called, have been explained to students in a variety of textbooks. One of the most lucid descriptions of these criteria, and well worth reproducing here, is presented by Bart Ehrman, who describes six criteria that have been developed for ascertaining which variant is closest to the original. All of the criteria work together and need to be applied to every passage in the New Testament that contains variant readings.

1. The Number of Witnesses That Support a Reading

Given this abundance of evidence, one might suppose that a fairly obvious criterion for deciding which reading is original is to count the witnesses in support of each (different) reading and to accept the one that is most abundantly attested. Suppose, for example, that for a given verse there are 500 witnesses that have one form of wording and only six that have a variant form. All other things being equal, one might suspect that the six represent a mistake.

The problem, however, is that all other things are rarely equal. If the six witnesses, for example, all derive from the third and fourth centuries, whereas the 500 are all later, from the fifth to the fifteenth centuries, then the six may preserve an earlier form of text that came to be changed to the satisfaction of later scribes. Thus, simply counting the witnesses that support a certain form of the text is generally recognized as a rather unreliable method for reconstructing the original text.

2. The Age of the Witnesses

The form of the text that is supported by the oldest witnesses is more likely to be original than a different form found only in later manuscripts, even if these are more numerous. Most scholars recognize that this principle is better than simply counting the manuscripts, but it too can be problematic. For example, it is possible for a sixth-century manuscript to preserve an older form of the text than say, a fourth-century one. This would happen if the sixth-century manuscript had been produced from a copy that was made in the second century, whereas the fourth-century manuscript derived from one made in the third.

3. Quality of the Witnesses

In a court of law, the testimony of some witnesses carries more weight than that of others. If there are two witnesses with contradictory testimony, and one is known to be a habitual liar, drunkard, and thief, whereas the other is an upstanding member of the community, most juries will have little difficulty deciding whom to believe. A similar situation occurs with manuscripts. Some are obviously full of errors, for instance, when their scribe was routinely inattentive or inept, and others appear to be on the whole trustworthy. The best manuscripts are those that do not regularly preserve forms of the text that are obviously in error.

4. The Geographical Spread of the Witnesses

An even more useful criterion involves the geographical distribution of the different forms of the text, especially among the earliest manuscripts. Suppose that our manuscripts support two different forms of a passage, one found only among manuscripts produced in a specific geographical area (say, southern Italy), and other found in witnesses spread throughout the Mediterranean (say, Northern Africa, Alexandria, Syria, Asia Minor, Gaul, and Spain). In this case, the former is more likely to be a local variation reproduced by scribes of the region, whereas the other is more likely to be older since it was more widely known.

The foregoing criteria often have a cumulative effect in helping scholars decide what the original text was. If one form of reading, for example, is found in geographically diverse witnesses that are early and of generally high quality, then there is a good chance that it is original. This judgment has to be borne out, however, by two other factors.

5. The Difficulty of the Reading

Scholars have found this criterion to be extraordinarily useful. We have seen that scribes sometimes eliminated possible contradictions and discrepancies, harmonized stories, and changed doctrinally questionable statements. Therefore, when we have two forms of a text, one that would have been troubling to scribes—for example, one that is possibly contradictory to another passage or grammatically inelegant or theologically problematic—and one that would not have been as troubling, it is the former form of the text, the one that is more “difficult,” that is more likely to be original. That is, since scribes were far more likely to have corrected problems than to have created them, the comparatively smooth, consistent, harmonious, and orthodox readings are more likely, on balance, to have been created by scribes. Our earliest manuscripts, interestingly enough, are the ones that tend to preserve the more difficult readings.

6. Conformity with the Author’s Own Language, Style, and Theology

With the preceding criterion we were interested in determining which form of a passage could be most easily attributed to scribes who copied the text. With our sixth and final criterion we are interested in seeing which form of a passage would be easiest to ascribe to the author who originally produced the text in light of its vocabulary, writing style, and theology. If two forms of a passage are preserved among the New Testament manuscripts and one of them contains words, grammatical constructions, and theological ideas that never occur in the author’s writings elsewhere (or that conflict with his other writings), then that form of the text is less likely to be original than the other.

Taken from Ehrman’s The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings (495-98).

In many textbooks the first four criteria, or a combination of them, are categorized as “external evidence” because the analysis is external to the author. The focus is entirely on the texts themselves. The last two criteria are categorized as “internal evidence” because the evaluation of the manuscripts concerns the authors of the autographs and the scribes who copied them. This may seem complicated, but it is not. Take, for example, John 4:1 (“Now when Jesus knew that the Pharisees had heard that Jesus was making and baptizing more disciples than John ...”). Instead of “Now when Jesus knew…,” some manuscripts read “When the Lord knew….” This shift from “Jesus” to “Lord” may not seem very different, but it fails the internal evidence test because the use of “Lord” is contrary to the narrative flow of the Gospel, which consistently uses “Jesus.” John does not refer to Jesus as “Lord” until after the resurrection. The intrinsic probability is that John wrote “Jesus” in 4:1.

Fig. 6.16: Note the scribe’s comment in the margin, which is to the left of Heb 1:3, Codex Vaticanus.

Because the ink was faded, at some point a later scribe decided to write over each letter. When something seemed unclear, he felt free to “correct” it. There is an odd comment in the margin at Hebrews 1:3, where a later scribe, frustrated that someone had changed something unnecessarily, scribbled the following in the margin: “Fool and knave! Can’t you leave the old reading alone and not alter it?” (taken from Metzger, Manuscripts, 74).

6.5 Today’s New Testament: Chapter and Verse Numbering

Most readers of the New Testament today don’t think about the chapter divisions, verse numbering, and punctuation. These features are simply assumed and applied to memory. Take, for example, John 3:16, which has become one of the most well known verses in our society, even among non-Christians. The simple mention of “John 3:16” immediately conjures up its message for most Christians. The name of the verse functions like an abbreviation. Chapter and verse numbering is certainly convenient, beneficial, and here stay. Many of us could not imagine the bible without these numerical references.

It is often surprising to readers of the New Testament (and the bible for that matter) that ancient manuscripts did not use chapters, verses, or punctuation. It is also surprising for many to learn that unlike in modern writing, there were no gaps between words. Consider the following example: “inthebeginningwasthewordandthewordwaswithgodandthewordwasgod.” This is how Paul, Mark, John, and all of the New Testament writers would have written their autographs. Now imagine the same sentence without vowels. That is how the Hebrew text would have looked in the first century.

Fig. 6.17: Fresco of Cardinal Hugh of St. Cher at his writing table by Tommaso da Modena, Basilica San Nicolo, Traviso, Italy, 1352.

The first chapter divisions begin to take place in the fourth century. As the public reading of the New Testament became more common in liturgical settings, the division would have allowed for more organization and convenience. Chapter divisions as we know them in modern translations, however, can be traced to the thirteenth century, when a University of Paris theology professor by the name of Stephen Langton started to organize the Latin Bible into chapters to facilitate his work on commentaries. He later became the Archbishop of Canterbury and a prolific biblical scholar. The first bible to be published (in Latin) with chapter divisions was in 1240 by Cardinal Hugh of St. Cher. In 1330, Jewish scribes appropriated the same divisions for their scriptures.

Fig. 6.18: Robert Stephanus’ Greek-Latin New Testament with chapter and verse numbering.

Verse divisions were introduced three centuries later by a Protestant book printer living in France, named Robert Stephanus (and also known as Robert Estienne). After French church authorities condemned Stephanus for printing Greek and Latin bibles, he fled with his family to Geneva. On route, while on horseback, Staphanus began to divide the New Testament into the verse system that we use today. In 1555, Stephanus printed a Latin bible with New Testament verses, which became the standard for numerical referencing in English bibles. The first of these was the Geneva Bible in 1560, which preceded the famous King James Version by 51 years.

The verse divisions should be viewed as being entirely arbitrary. They were not organized in a methodical manner. They do not conform to particular literary units within genres. And they do not represent the thought patterns of the New Testament authors. While they are certainly convenient for locating specific texts and as reference markers, they should not be used to guide interpretation.

Try the Quiz

Bibliography

Aland, Barbara, Kurt Aland, Johannes Karavidopoulos, Carlo M. Martini, and Bruce M. Metzger, eds. Nestle-Aland – Novum Testamentum Graece. 28th revised ed. Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 2012.

Aland, K. and B. Aland. The Text of the New Testament. 2d ed. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1990.

Black, D. A. New Testament Textual Criticism: A Concise Guide. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1994.

Ehrman, Bart D. The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

_____. The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture: The Effect of Early Christological Controversies on the Text of the New Testament. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Epp, Eldon Jay. “Textual Criticism.” In Anchor Bible Dictionary. Edited by David Noel Freedman. New York, NY: Doubleday Publishers, 1993, 412-435.

Gamble, Harry Y. Books and Readers in the Early Church: A History of Early Christian Texts. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995.

Greenlee, J. H. An Introduction to New Testament Textual Criticism. 2d ed. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 1995.

Longenecker, Richard N. “Ancient Amanuenses and the Pauline Epistles.” In New Dimensions in New Testament Study. Edited by Richard N. Longenecker and Merrill C. Tenney, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1974. Pp. 281-97.

Metzger, B. Manuscripts of the Greek Bible: An Introduction to Greek Paleography. New York: Oxford, 1981.

Metzger, B. and Bart D. Ehrman. The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Parker, David. The Living Text of the Gospels. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Richards, Ernest R. The Secretary in the Letters of Paul. WUNT 42. Tübungen: Mohr Siebeck, 1991.

Wegner, P. D. A Student’s Guide to Textual Criticism. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2006.