Module Five

Earliest Christianities

5.1 Introduction

Fig. 5.1: Wall painting of the Healing of the Paralytic from the Baptistry of the Domus ecclesiae, Duro Europos, Syria. This may be the oldest image of Jesus that we have today, dating to about 235 CE.

When most people today think about early Christianity, they often assume that it was unified, peaceful, and monolithic in its thought. After all, since the writings of the New Testament are often read as a single book, the ideas and groups that are found in them tend to blend together into a homogeneous community that shared common beliefs and practices. There is no question that early Christian groups, as they are represented in the New Testament, shared a common religious identity and beliefs. Central to their commonness was the belief that Jesus of Nazareth was the Messiah, who has come to restore humanity through his death and resurrection. They also believed in one God, they believed in the presence of the Holy Spirit, life after death, practiced baptism, the Eucharist, and awaited the second coming of Jesus at the end of the age. But, alongside the commonness was a range of differences in beliefs and practices by groups that would have identified themselves as Christians. By examining the different groups that are either implicit or explicit in the New Testament, we get a fairly good indication that Christianity in the second half of the first century was far from being homogeneous.

5.2 The Diversity of Early Christian Groups

The observation that early Christianity was diverse is not new. Approximately one hundred and fifty years ago, Ferdinand Christian Baur (1792-1860) argued that earliest Christianity was shaped by the division between Pauline (Paul and his followers) and Petrine (Peter and his followers) versions of Christianity. In the early part of the twentieth century, Walter Bauer (1877-1960) further challenged the prevailing assumptions of first-century theological unity by arguing that historians can no longer use terms like “orthodoxy” and “heresy” in historical reconstructions of earliest Christian thought. For many historians standing on the shoulder of Bauer, “orthodoxy” and “heresy” were viewed as more appropriate categories from the council of Nicea (325 CE) onward.

Fig. 5.2: Late Roman apse mosaic from the basilica of Santa Pudenziana, Rome, 4th century. Christ is depicted as a Roman teacher, sitting on a jewelled throne, wearing a golden toga with purple trim, which represented authority. He is surrounded by his Apostles who are wearing senatorial togas.

Early Christianity is rooted in the historical Jesus of Nazareth who ministered to fellow peasant Jews in the late twenties of rural Galilee within the theological and cultural context of Judaism, before the emergence of Christianity as a separate religion. But this is by no means the whole story. Early Christian thought as it appears in the New Testament largely represents interpretations of Jesus’ teachings, actions, and identity after his death. Scattered across the Roman Empire, the early followers of Jesus interpreted their new faith within a variety of ethnic settings, religious contexts, political conflicts, and economic strata. Social historians who have attempted to trace the development of early Christian thought by isolating various early Christian groups and their beliefs have commonly referred to the earliest groups of disciples as the Jesus Movement, though the use of the term “movement” is not intended to convey the common connotation that it contained strictly charismatic and anti-institutional tendencies. The beginning of Christianity, which is exceedingly difficult to pinpoint, can be attributed to these earliest followers.

Fig. 5.3: Wall painting of Christ walking on water with the disciples in the boat. From the Baptistry of the Domus ecclesiae, Duro Europos, Syria. This is also a very early image of Jesus, dating to the middle of the 3rd CE.

Our exploration of early Christianity is divided into two sections. The first section focuses on the diversity of early Christian groups which are sorted into three categories: (1) groups that are implied, or are “behind,” the New Testament; (2) groups that are represented by the writers, or are “of,” the New Testament; and (3) groups that post-date, or are “beyond,” the New Testament. The subtitles are not as accurate as they could be, but they are convenient. The second section of this chapter focuses on the use of the Jewish scripture in the development of early Christian identity and belief.

5.2.2 Groups Behind the New Testament

The writings of the New Testament imply or mention groups that would have identified themselves as followers of Jesus. Many of the groups opposed the ideas that were taught by the New Testament writers, but some were the precursors of communities that endorsed them.

Judaizers

Fig. 5.4: Mosaic of the Apostle Paul, Museo arcivescovile di Ravenna, Italy. Early 6th century.

Some New Testament writers make mention of Jesus followers who had alternative views on such topics as ethics, salvation, ritual, the nature of God, and apostolic authority. One such group was the Judaizers. These were Christians from Palestine who advocated, in contrast to Paul, that Gentile converts were required to undergo circumcision and obey the dietary laws as they were prescribed in the Torah. They believed that these and other legal requirements functioned as the boundary markers that identified the people of God. The Galatian Christians, who were apparently susceptible to the teachings of the Judaizers, were warned by Paul not to abandon the gospel that he originally preached to them. The Corinthian Christians seemed also to have been influenced by Judaizers, but the issues in 2 Corinthians have more to do with Paul’s apostolicity. In 2 Corinthians, Paul’s apostolic authority seems to be challenged by a group of Jewish Christians who have again followed Paul and attempted to undermine his teachings. A considerable amount of ink has been spilt over the past two centuries in the attempt to identify the Judaizers, be they members of one group or several. One of the most common proposals has been that they were Jerusalem Christians, perhaps led by James or Peter.

Opponents of John’s Community

Fig. 5.5: Giorgio Vasari “The Incredulity of St. Thomas.” Basilica of Santa Croce. 1572. This scene depicts Thomas’ encounter with the risen Christ (John 20:26-28).

Several examples of groups who followed Jesus have been detected in the Gospel of John and the epistles of John. In the Gospel, scholars have identified three groups of Christians that were distinct from the writer and his congregation (or the so-called Johannine community): Christian Jews within the synagogues, Jewish Christians who left the synagogues to form their own churches, and Jewish Christians represented by the Twelve, especially Peter, Philip, and Andrew.

Fig. 5.6: Fresco, by Damiane, “Jesus Christ and St. John the Apostle, Ubisi, Georgia. 14th century.

More recently, some scholars have argued that an early Gnostic Christian group can also be detected. Gnosticism (which comes from the Greek word gnosis meaning “knowledge”) was a complex and varied system, but it had in common a dualism that separated the material/physical (which was considered evil) and the spiritual (which was considered good) components of humanity. Spirits were believed to be trapped in physical bodies and could only be released (or saved) through the communication of special knowledge. Elaine Pagels, for example, has suggested that John’s Gospel and the epistles appear to be responding to a Gnostic group that followed Jesus, but denied that he actually came in the flesh—much like the later Docetists who believed that Jesus only appeared to be physical, but in actuality was a spirit. On the basis of the numerous similarities between the Gnostic Gospel of Thomas and John’s Gospel, Pagels proposes that the Johannine community was partly in conflict with the so-called Thomas Christians. Thus, John’s statements about Jesus coming in the flesh and his use of Thomas’ confession (“My Lord and my God”) after he touched the risen Christ are intended to counter the Gnostic claims (20:24-28). Similar statements about Jesus coming in the flesh in other New Testament texts (e.g. 1 Tim 3:16) have led some to believe that Gnostic influences within nascent Christianity were more widespread than once thought.

The Q Christians

Gospel scholars who accept the Two-Source theory—that Matthew and Luke used Mark and a sayings source called Q (for the German Quelle meaning “source”)—have pointed to what might be the oldest detectable Christian group. No list of examples is ever complete without its mention. This hypothetical Q document (often called the Q Gospel and discussed in chapter 8 below) is dated to the 40s CE and is often attributed to the first generation of Christians who led an itinerant ministry. As wandering Christian prophets, they aimed their mission at the Jews in Palestine. After the failure of the mission to Israel and the devastation caused by the Jewish War (66-70 CE), the community settled in Syria, where it received significant theological inspiration from the community associated with the Gospel of Mark. It was at this point that it oriented its efforts toward the Gentile mission, as it was eventually recorded in Matt 28:16-20. If the reconstruction of the Q Gospel is correct, then the material that it does not include, in comparison to the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke), may be indicative of their beliefs. Two of the more glaring omissions are an infancy account and a resurrection account. The aim of the Q Gospel (as is the case in the Gospel of Thomas) seems to have been the preservation of sayings attributed to Jesus, and not the cross and resurrection of Jesus.

Fig. 5.7: Mosaic of Risen Jesus with the disciples, Basilica di Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna, Italy. 6th century.

House Churches

Fig. 5.8: Ruins of a house church, with chapel on the left. Duro Europos, Syria. Early 3rd century.

Overlapping the itinerant preachers was a more structured push for the establishment of churches beginning in Jerusalem and Judea, and extending into Syria and Asia Minor (the so-called Gentile churches). These early churches, however, should not be equated with buildings designated for communal worship as they are today. They should instead be viewed as communities consisting of people from varied social and ethnic backgrounds, within a shared geographical area, who expressed a common belief in Jesus as Messiah and savior. In fact, the earliest church building discovered by archaeologists, in the town of Dura in Eastern Syria, dates to the middle of the third century. Communal worship and fellowship in the first century would have been held in people’s homes, which are called “house churches.” These were not large gatherings by our standards. Many Christians today are surprised to hear that the church in Corinth, for example, with all its problems and vulnerabilities (according to 1 Corinthians) would have consisted of approximately fifteen people in the middle of the first-century.

Fig. 5.9: Remains of a 5th century Byzantine church at Sardis (one of the seven churches in Revelation), built on the site of the Artemis Temple (5th century BCE).

Interaction among early communities in different cities was limited. While they may have been founded by common itinerant prophets or teachers, such as the Apostle Paul or John the Elder, they each retained their autonomy and essentially developed on their own, interacting with and being influenced by local religious ideas and customs. On occasion, inter-house church relations were strained, as is indicated by the admonishment directed at the Asian churches in Revelation 2 and 3. On other occasions relations with fellow members who held differing ideas were severed, as may be the case in John the Elder’s warning (in 3 John) to a certain Gaius about Diotrephes, an alleged ambitious upstart who disregarded the teachings of the Johannine community.

5.2.3 Groups of the New Testament

When attention is turned to the beliefs of Christians represented by the New Testament writers, we are on firmer historical ground, but we find no less diversity. The New Testament writings were composed during the second half of the first century, over approximately a fifty-year period, primarily in Asia Minor and Syria, by Jewish Christians (except perhaps for Luke) who were attempting to legitimize their new-found faith in Jesus as God’s messiah in response to mostly Jewish, and some Roman, opposition. As is the case with all nascent religions, formulations of belief needed to draw on existing language, symbols, myths, rituals, worship practices, and authoritative texts and traditions. The culture was the cradle. Since the Greco-Roman world accommodated numerous religious and philosophical traditions, one of them being Judaism, the options for expressing the content of early Christian faith were immense. So what kind of diversity do we find in the New Testament writings? The following summary of prominent groups represented by the New Testament writers captures some of the breadth of early Christian thought.

Fig. 5.10: Fresco of apostles dressed in Roman togas, discovered in the hypogeum of the Aurelii was a catacomb built for the prestigious Aurelli family. Rome, early 3rd century. Many of the early Christian groups believed themselves to be followers of one or more of the apostles.

The Evangelists

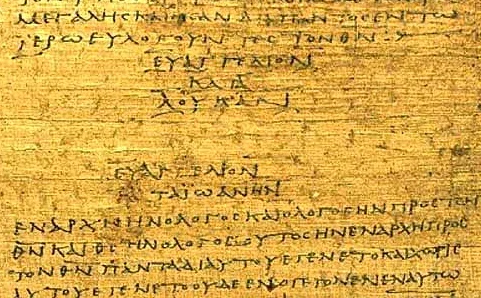

Fig. 5.11: P75, Bodmer Papyrus XIV-XV, late 2nd/early 3rd century. This part of the Greek manuscript contains the end of Luke’s Gospel, which is entitled “Gospel according to Luke,” and the beginning of John’s Gospels, which is entitled “Gospel according to John.” In the middle of this photo, one can easily pick out the word ∆OYKAN, which means “Luke.”

One of the most effective ways of demonstrating some of the diversity among early Christian groups is by carefully comparing the four Gospels. Since the Gospels are anonymous, the writers are technically designated as “evangelists,” meaning spreaders of the “good news.” Scholars are not sure exactly when the titles, which contain the names of the evangelist (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John), were added. There is more agreement, however, that the evangelists were leaders or even pastors of early Christian communities.

Fig. 5.12: No manuscripts from Tatian’s Diatessaron, which was originally written in Syriac, have survived. However, some early manuscripts from the Syriac bible (OT), called the Peshitta, have survived. This is an Illustration from the book of Job. Paris Syriac manuscript 341 f.46R. Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris. 6th century.

At the popular level of religious worship, most Christians do not read the Gospels comparatively. As a result, the events that are narrated are often harmonized and rolled into one overarching story. In a real sense, the four Gospels are turned into one Gospel, which distorts their unique contributions. This practice is not new. It has occurred ever since the four Gospels circulated together as authoritative religious documents. One of the most well known harmonizing practices in the early church was that of Tatian’s (110-180 CE) Diatessaron (meaning “through [the] four [Gospels]”), which forced all the Gospels into one chronological, historical, and theological mold. Ancient practices of harmonizing the Gospels were often conducted for apologetic and theological reasons. The church leaders (since most laypersons were illiterate) needed to respond to the inconsistencies in the four accounts that were highlighted by their adversaries.

Today, in our highly literate culture, most Christians read the Gospels vertically instead of horizontally, which is easy to do since they are placed sequentially in a codex (or book). One begins with Matthew and ends with John. By the time all four are completed, the stories have rolled into one. The problem is amplified when the reading program is governed by quantitative, instead of qualitative, agenda such as the so-called “one year” Bible reading program. Harmonizing practices also appear in popular expressions of Christian faith, such as Nativity scenes in plays and on Christmas cards and calendars where Matthew’s infancy account is blended with Luke’s. In films such as King of Kings (1961), The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965), Jesus Christ Superstar (1973), Jesus of Nazareth (1977), and the The Passion of the Christ (2003), the harmonizing of the Gospels is even more noticeable.

Fig. 5.13: Peter Paul Rubens’ “Mary annointing Jesus feet.” Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. c. 1618.

Mark Goodacre provides a telling example from a scene in Jesus Christ Superstar where Mary Magdalene is characterized as a prostitute who anoints Jesus before his death and is then opposed by Judas who complains about the cost of the anointing oil. This scene draws together the following elements from all four Gospels: (1) the anonymous woman who anoints Jesus’ feet in Mark 14 and Matthew 27, (2) the anonymous woman “sinner” who anoints Jesus in Luke 7, (3) the name “Mary, called Magdalene” in Luke 8:2, (4) Mary of Bethany who anoints Jesus in John 12, and (5) Judas who complains about the anointing also in John 12. Watching this one scene on a cursory level gives no indication of the sources used.

Fig. 5.14: Click on the image to expand the text. This is a synopsis of Jesus’ baptism in Matthew, Mark, and Luke from the NRSV. When the scene is read in parallel (i.e. horizontally), it is much easier to see the nuances. Courtesy of Accordance Bible Software.

When the Gospels are read “horizontally”—that is, alongside one another in a comparative way—they appear in an entirely different light than when they are read “vertically” (starting with Matthew and ending with John). This practice of reading dramatically reveals both the similarities and the differences. It reveals that all of the Gospels are narratives that share a common general plot, antagonists, protagonists, climax, and resolution. All have Jesus as their main character and hero, who is portrayed as the messiah, Son of God, deliverer of God’s people, and the prophet predicted in the Jewish scriptures. All of them include Jesus’ teaching about redemption, salvation, and discipleship. All of them portray Jesus as performing miracles, and all of them describe his passion—his trial, suffering, death, and resurrection (though in Mark it is implied). Alongside the similarities, however, a horizontal reading sheds light on the numerous differences, some of which are slight, like a shift in emphasis or writing style, while others are more substantial, like meanings attributed to Jesus’ messianic identity, role, death, and resurrection.

Synoptic Gospels

Among the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke), which share the same basic chronology, emphasize the kingdom of God, and contain many common events and sayings, divergences are abundant. Again, these become visible when we read the accounts alongside each other. A helpful tool in this regard is a Gospels Synopsis because it sets the accounts in parallel columns. Consider a few examples. Each evangelist omits material found in the other two. Each contains unique incidents. Some of the shared events are put in a different order, such as the last two temptations of Jesus in Matt 4:5-11 and Luke 4:5-13. Also some sayings of Jesus are placed in entirely different contexts. Take, for example, the saying “No one can serve two masters; for either he will hate the one and love the other, or he will be devoted to the one and despise the other. You cannot serve God and mammon.” In Matthew (6:24), the saying is found in the context of the Sermon on the Mount, but in Luke (16:13), it appears verbatim in the context of parables much later in the story.

Fig. 5.15: Illustration of Mark the evangelist. Lindisfarne Gospels, British Library, London. 7th century.

Fig. 5.16: Illustration of Matthew the evangelist. Lindisfarne Gospels, British Library, London. 7th century.

Fig. 5.17: Illustration of Luke the evangelist. Lindisfarne Gospels, British Library, London. 7th century.

The three evangelists also emphasize different themes, most notably in their portrayals of Jesus. To mention a few, in Mark, Jesus appears as the concealed messiah who alone preaches the kingdom of God (in contrast to Matthew where the disciples also preach it). In Matthew, Jesus is portrayed as a new Moses who brings the correct interpretation of the Law. In Luke, Jesus is portrayed as a rejected prophet who is concerned with the welfare of social minorities and outcasts. In Mark, the earliest of the three, the resurrection account is subtle and incomplete when compared with the other two Gospels, which raises the question of how Mark understood it. One of the most glaring omissions in Mark is the birth and infancy account. Did Mark not know this tradition? If he knew of it, why did he not include it? Did he not believe it?

Comparing John and the Synoptics

When John is brought into the picture and compared with the Synoptics, the divergences escalate. Whether the Johannine evangelist knew the Synoptic Gospels and thus intended the differences or had no knowledge of them continues to be debated, but this is not the issue before us. What the differences make clear, again, is that early Christianity was multi-dimensional. The differences are particularly stark in John’s portrayal of Jesus.

Fig. 5.18: Illustration of John the evangelist. Lindisfarne Gospels, British Library, London. 7th century.

In John, Jesus is portrayed as the incarnate preexistent Word of God whose speeches and miraculous deeds (called “signs”) focus on his divine identity and intimate relationship with the Father, which he publicly communicates. Yet as a divine figure, he is still subordinate to God. John’s focus is not on Jesus’ preaching of the kingdom of God, messianic concealment, the Mosaic Law, or social justice. Instead, the focus is on belief in Jesus as the Christ and Son of God who has come in the flesh. Without drawing out each occasion where John differs from the Synoptics, a list of a few examples should suffice to show John’s uniqueness. The following are in no particular order.

(1) Only John has Jesus cleansing the temple at the beginning of his ministry, rather than at the end. In the Synoptics, the temple action constitutes Jesus’ last public act; yet in John it his first. In the Synoptics, it is met with fierce opposition, and even a call for his death (Mark 11:18). In John there is no repercussion. Instead, the event is spiritualized and used to forecast Jesus’ resurrection (2:13-22).

(2) In John, Jesus dies on the day of preparation, and not on the Passover as the Synoptics record. In John 18:28 the crucifixion takes place on 14 Nisan, the day before Passover. In the Synoptics (Mark 14:12), the last supper (which was the Passover meal) and the crucifixion occurred on 15 Nisan. Again, it is interesting how John tends to spiritualize the event by having Jesus die on the “day of Preparation for Passover, at noon” (19:14) which corresponds to the time of the killing of the sacrificial animals. In John, Jesus is compared to the Passover lamb of Exodus.

(3) In John, the Baptist repudiates any identification with Elijah (John 1:21a), but in the Synoptics Jesus identifies him as an Elijah figure (Matt 11:14; 17:10-13; Luke 1:17).

(4) In John, Jesus teaches in extended sermons rather than in short parables. There are no kingdom parables in John.

(5) In John, Jesus is confessed as messiah from the beginning of his ministry (1:41), but in the Synoptics this confession comes later in the story (Mark 8:27-30) and marks the turning point of his ministry.

(6) In John, both the disciples and Jesus publicly declare his exalted identity. In the Synoptics, neither Jesus nor his disciples speak publicly about his exalted status during his lifetime. His true identity is revealed in snippets: in private epiphanies, at his baptism, to the inner circle at his transfiguration, and in Peter’s confession. In Mark especially, his messianic identity is intentionally secretive.

(7) In John, Jesus is presented as more divine than human. It has commonly been said that in comparison to the Synoptic portrayals, the Johannine Jesus “hardly touches the ground.” His divine status is regularly acknowledged and occasionally recognized by other characters, which may explain why John’s Gospel contains no actual baptism, transfiguration, or temptation. If John knew accounts, he may not have deemed them as necessary because Jesus’ entire mission seems to be presented as an epiphany.

(8) In John, Jesus never casts out demons.

(9) In the Synoptics, Jesus espouses the causes of the poor and the oppressed, but in John he has nothing to say about them.

(10) In John, there is no Lord’s Supper prior his death. While many have argued that John 6 is based on Eucharistic celebrations, the chronology and event is significantly different from that of the Synoptics.

(11) In the Synoptics, Jesus’ primary opponents are the Sadducees, Pharisees, scribes, and Herodians; whereas in John, they are called “the Jews” and “the world.”

(12) In the Synoptics, Peter is the most prominent of the apostles, whereas in John the “beloved disciple” takes the lead role.

(13) In John, Jesus does not pray the “Lord’s Prayer.”

(14) In John, the disciples are not sent out on a mission during Jesus’ lifetime. Instead, he sends them after the resurrection.

Paul and the Other Writings

When the rest of the New Testament is brought into the mix, the differences remain. Some of them are theologically significant. It is important to emphasize that these difference are not necessarily incoherent, but they do point to varied perspectives on a host of topics. For example, many biblical scholars have observed that Jesus’ teachings differ from that of the Apostle Paul. Whereas Jesus (of the Synoptic tradition) is concerned about the kingdom of God, Paul has little to say about it. In fact, Paul hardly mentions anything about Jesus’ teachings. Instead, Paul focuses on the effects of Jesus’ death and resurrection.

Another significant theological divergence has to do with the meaning of Jesus’ death. Mark, for example, understands the death as a pattern of faithfulness for all followers, whereas Hebrews understands it as a sin sacrifice.

Fig. 5.19: Adamo Tadolini’s “Statue of St. Paul,” St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican. 1838.

The role of women in the fledgling Christian communities also varies, sometimes in the writings of the same author. The early writings of Paul, for instance, appear to be much more relaxed about leadership positions for women than the later writings (assuming that 1 and 2 Timothy were written by him). As Christian communities become more institutionalized well into the second century, women appear to lose authority and leadership roles.

The role of the Jewish law, which is one of the most difficult topics in the New Testament, also varies. Matthew, for instance, appears much more traditional than does Paul. In Matt 5:17-19 Jesus endorses strict obedience to the law, so long as it is grounded in compassion. Yet in Paul’s letters, observances of the law, particularly circumcision, are not required for converts to Christianity. In Galatians, Paul argues that the law served as a temporary means of guidance and discipline for the Jews until God fulfilled his promise to Abraham by sending Christ. Paul tells the gentile converts in Galatia that it is their faith, as exemplified by Abraham, which bring about righteousness. Paul’s critique of the Law was not that it was pointless, but rather that it excluded some people from God’s salvation. In short, one did not need to become Jewish in order to remain a Christian.

Fig. 5.20: Greek Orthodox icon of the Apostle Paul, by Father Pefkis, Trikala, Greece.

As a final example, consider the differing views on the role of government. In Romans 13:1-2, Paul leaves little, if any, room for resisting authority when he writes, “Every person is to be in subjection to the governing authorities. For there is no authority except from God, and those that exist are established by God. Therefore whoever resists authority has opposed the ordinance of God; and they who have opposed will receive condemnation upon themselves.” Whereas Luke implies that God (and hence his followers) subverts social structures. When some of the disciples are arrested for not complying with a ban on their Christian teaching, Luke writes,

When they had brought them, they stood them before the Council. The high priest questioned them, saying, “We gave you strict orders not to continue teaching in this name, and yet, you have filled Jerusalem with your teaching and intend to bring this man’s blood upon us.” But Peter and the apostles answered, “We must obey God rather than men” (Acts 5:27-29).

5.2.4 Groups Beyond the New Testament

Fig. 5.21: Solidus (gold coin) with the head of Emperor Flavius Theodosius I. In circulation: 379-395 CE.

Diversity in early Christian thought extends beyond the New Testament well into the fourth century. Unfortunately, many of the early Christian writings that are not in the New Testament (called “extracanonical” writings) are no longer extant. Some may have been incorporated into other writings (such as Q was incorporated into Matthew and Luke), others disappeared due to lack of interest, and still others were destroyed by rival Christian groups that were more dominant. The destruction was particularly intense when in 380 CE Emperor Theodosius made Christianity the official state religion of the Roman Empire and outlawed all theological thinking/writing that deviated from the “common” faith as it was expressed in the first ecumenical council of Nicea in 325 CE. Not all of the writings that deviated from the official theology were destroyed, however. Prior to Emperor Constantine (306-337 CE), who initiated the push for a unified, empire wide, Christianity, the basic institutional unit of Christianity was either the local church assembly or the diocese, which was the region overseen by a bishop. Since both travel and communication was prohibitive by our standards, variance was inevitable.

What remains of the Christian writings from the first one hundred years provides an interesting window into the diversity that partly overlaps the New Testament. Lists of early Christian extracanonical writings within the first hundred years of Christianity, up to about 130 CE, will vary from scholar to scholar. The following is a fairly liberal list of writings that would have represented various groups identifying themselves as Christian.

Gospel of Thomas

Gospel of Peter

Infancy Gospel of Thomas

Secret Gospel of Mark

Unknown Gospel (Papyrus Egerton 2)

Gospel of the Ebionites

Gospel of the Nazareans

Gospel to the Hebrews

Acts of Paul and Thecla

1 Clement

Didache

Letters of Ignatius

Letter of Polycarp

Letter of Barnabas,

Preaching of Peter

Fragments of Papias

Shepherd of Hermas

Apocalypse of Peter

Some of these writings were consistent with the broader theological ideas found in the New Testament (such as 1 Clement, Shepherd of Hermas, Didache, the letters of Ignatius, Polycarp, and Barnabas), whereas others were inconsistent, and considered aberrant.

Fig. 5.22: Fresco of Justin Martyr by Theophanes the Cretan and his son Simeon, The Church of St. Nicholas Stavronikita Monastery, Mount Athos, Greece. 1546.

For centuries our knowledge of the extracanonical writings that represent the aberrant groups came mostly from their rivals, the Church Fathers (e.g. Irenaeus) and the apologists (e.g. Justin Martyr), who represented the majority view. “Church Fathers” is a designation for the religious authorities (such as bishops, priests, and presbyters) of a form of Christianity that eventually was identified as orthodox, in contrast to those forms of Christianity that were later officially determined as heretical. The apologists were mainly philosophers who argued for the superiority of what became the orthodox position. Unfortunately, the few manuscripts from “aberrant” groups that survived were not sufficient for a thorough reconstruction.

All of this changed in 1945 when the so-called Gnostic library was discovered near the town of Nag Hammadi, Egypt. The story of the discovery is extraordinary, full of drama, intrigue, and wonder. It has revealed a picture of early Christianity that is more diverse than could have been previously imagined—even more diverse than the Christianity of today. For many, the discovery of these documents has reinvigorated interest among both academics and laypersons in the study of early Christian writings, ideas, and groups.

Fig. 5.23: Codices discovered at Nag Hammadi in 1945.

Describing all of the diverse groups that considered themselves Christian, yet differed considerably from those that are represented by the New Testament writings is an immense undertaking, but a brief listing of a few groups should suffice in drawing a rough sketch. Again, these are general groupings represented by the extracanonical Christian writings to the middle of the second century.

Gnostic Christians

Fig. 5.24: First page of the Apocryphon of John, one of the gnostic writings found at Nag Hammadi, Egypt. The Coptic Museum, Cairo. 2nd century CE. Click to see an enlarged image.

This was not a unified group. Gnostic Christianity is more of a general collective category. Gnostics did not always agree among themselves. Some argued that Jesus was not human, but completely divine. Yet his divine nature was not equated with the God of the Old Testament who created the (evil, material) world. Others believed that Jesus was both human and divine, as two separate beings in one. They believed that the divine being (called “the Christ”) came upon the human Jesus at his baptism, empowering him during his ministry, and then left him before his death. Concepts of divinity for Gnostics came out of polytheism. For example, some thought that Jesus was one of 30 gods; whereas others thought he was one of 365 gods. Despite the differences, Gnostics agreed that a special knowledge (Greek gnosis) was required for an individual to be saved from the entrapment of a physical body and a material world. Jesus was believed to be the emissary who brought the saving knowledge. All who believed him and recognized their imprisonment by the evil deity of this world were saved. Some of their writings included the Gospel of Thomas, the Infancy Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Philip, the Gospel of Mary, and the Gospel of Truth.

Marcionite Christians

Fig. 5.25: Manuscript illumination of the Apostle John and Marcion of Sinope (according to R. Eisler, The Enigma of the Fourth Apostle [Methuen & Co., 1938, p. 158, plate XIII]). J. Pierpoint Morgan Library MS 748, folio 150 verso. 11th century.

This group was dedicated to the teaching of a second century Christian scholar and evangelist, named Marcion of Sinope (c. 85 – c. 160), who advocated that the truth of Christianity resides only in the writings of Paul. For Marcion, Paul was the true apostle because the resurrected Christ appeared to him and imparted the true revelation. Marcion argued that Paul draws a sharp divide between the gospel of Christ and the Law of the Jews. As a result, the legal system of the Jewish scriptures (advocated by the Jews and Jewish Christians) played no role in the salvation plan of God. Marcion extended this divide further. He preached that the God of the Jewish scriptures is a vengeful, harsh, just, and even tyrannical demiurge; whereas the God of Jesus is merciful and loving. For example, Marcion could not reconcile the Old Testament commands of God to slaughter Israel’s enemies and the command of Jesus’ to love one’s enemies. For Marcion these were two unrelated and incompatible gods. The only correlation was that Jesus came to save people from the God of the Jews. Since Jesus opposed the God of the Jews who was the creator of this world, Jesus was not of this world. He did not even have a physical body. His appearance was only an illusion, but his spirit was real. He was neither born, nor did he die. Marcion’s movement spread across Asia Minor.

Marcion supposedly wrote the Antitheses, which contrasts the Jewish God and the God of Jesus (http://www.gnosis.org/library/marcion/antithes.htm), and the Gospel of the Lord, which consist of selections from Luke’s Gospel. Almost everything we know about him comes from his adversaries, most notably Tertullian’s work called Against Marcion.

While some of Marcion’s ideas appear to line up with the Gnostics, the differences place him outside of that categorization. Unlike the Gnostics, Marcion did not believe that a “spark of divinity” is present in every human being. Consequently, he denied that salvation is rooted in the recognizing of one’s own divine quality. He also did not see the emancipation from the physical body and a material world as the ultimate human struggle. Having said that, debate about Marcion’s connection with Gnosticism continues.

Adoptionist Christians

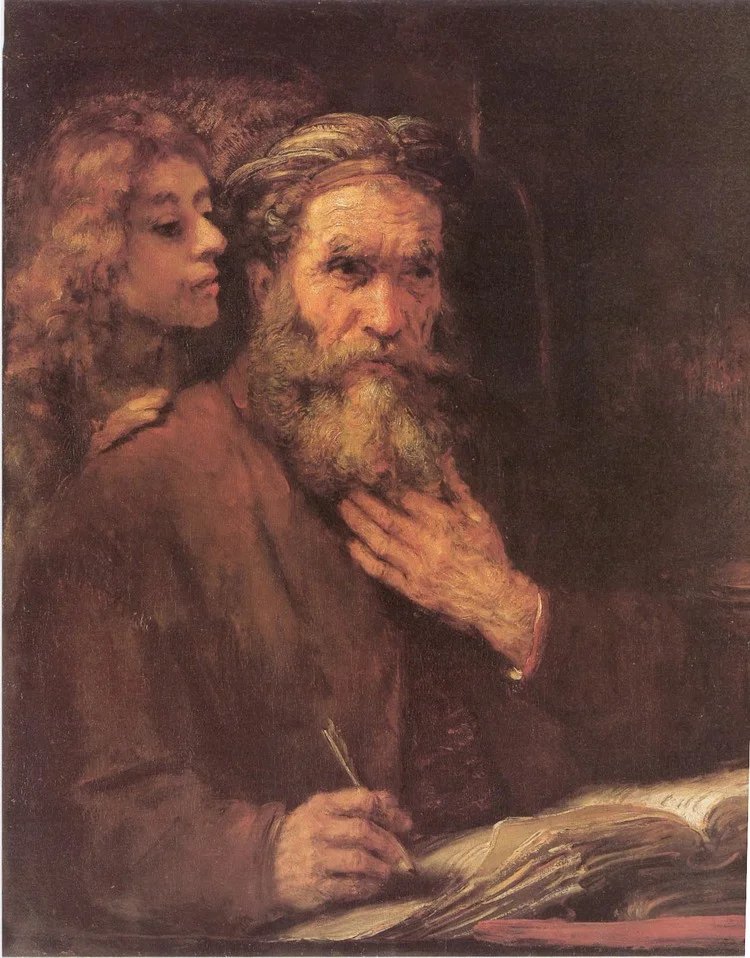

Fig. 5.26: Rembrandt’s “The Evangelist Matthew Inspired by an Angel.” Louvre-Lens, Lens, France. 1661. According to the Adoptionists, Matthew was the most Jewish of the New Testament writers.

This group consisted of Jews, living in the eastern parts of Palestine, who believed that Jesus was the messiah, adopted by God at his baptism when the Holy Spirit came upon him as a dove. As a result, Jesus was considered to be the most righteous of human beings and the wisest of teachers. His death was viewed as an atoning sacrifice for the sinful condition of humanity. God raised Jesus from the dead and exalted him to his right hand in heaven. Unlike the Gnostics and the Marcionites, who believed that Jesus was not human, but divine, the Adoptionist Christians believed the opposite: Jesus was thoroughly human and not divine. Thus, this group denied that Jesus existed prior to his birth and that he was born of a virgin. For the Adoptionists, there was only one God. Being consistent with traditional Jewish reasoning, they argued that if Jesus is God and the Father is God, there would have to be two Gods, which was repugnant to Jews. In contrast to the Marciontes, the Adoptionist Christians thought that Paul should be rejected as a blasphemer because he taught that the Law (especially the Jewish identity markers like circumcision, Sabbath, and dietary laws) is no longer relevant. Instead, this group appropriated a book similar to that of Matthew, but written in Hebrew.

5.3 Scripture in Early Christianity

Fig. 5.27: Caravaggio’s “Sacrifice of Isaac,” Uffizi Museum, Florence. 1603. The binding of Isaac (Genesis 22), known as the Aqedah, was interpreted in a variety of ways in early and rabbinic Judaism. For example, some rabbis argued that God was simply testing Abraham. Others argued that God simply wanted a symbolic sacrifice, like a spiritual surrender. One rabbi in the medieval period even argued that Abraham’s imagination led him astray since God would never command such an act. In the Targum to Genesis, Isaac wants to be sacrificed to prove his devotion. The early Christians applied the whole scene to the sacrifice of Jesus (e.g. Heb 11:17-19).

Scripture, or what Christians today call the Old Testament, was the most influential source in the development of early Christian identity and thought. Earliest Christians developed their theological thinking through interpretive methods that were very different from current historical approaches to the Bible. Since most of the earliest Christians were Jewish, common interpretive methods circulating in the Judaisms of the first century transitioned seamlessly into nascent Christianity. Early Jewish interpretation is most well known for its midrashic approaches. The word “midrash” in Hebrew means “commentary” and is related to the verb darash, which means, “to search.” Midrash has become synonymous with biblical interpretation in early and Rabbinic Judaism. The aim of midrash was essentially to contemporize the scriptures so that they might address current needs, be they legal, political, cultural, or religious. The underlying assumption was that scripture, which comes from God, conveys a fluidity of meaning for all generations and for all circumstances of life. Some midrashic interpretations appear to have established themselves as favored community readings and became inseparable from their scriptural sources. Midrash was practiced in three general ways called halakhah, aggadah, and pesher.

5.3.1 Halakhah

Halakhah (“way of going”), or halakhic midrash, refers to interpretations of scripture that are oriented toward meeting legal or ethical concerns. These often take the form of minor explanations or adjustments of biblical law. For example, the Septuagint (LXX), which is a Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures that was used more than any other version by the New Testament writers, contains numerous legal changes that presumably reflect the social conditions among the Jewish populace in Alexandria between the third and first centuries BCE. Assuming that the Septuagint translators used a Hebrew source that reflects the Masoretic Text (MT), the source for the modern Jewish Bible and the Christian Old Testament, consider the following comparisons that reflected social shifts in legal thinking.

In the first example, the slight shift from God finishing his work on the seventh day to the sixth day may well reflect a more established practice of the Sabbath in Alexandrian Judaism.

MT Gen 2:2

And on the seventh day God finished his work that he had done, and he rested on the seventh day from all his work which he had done.LXX Gen 2:2

And God finished the works that he had done on the sixth day and rested on the seventh day.

The second example expresses shifts in ritual legal practice enforced by the religio-political establishment. Lev 24:7 concerns weekly bread offering, whereas Deut 26:12 advocates a tithing that can be compared to our taxation system:

MT Lev 24:7

and you shall put pure frankincense with each rowLXX Lev 24:7

and you will add to the offering pure frankincense and saltMT Deut 26:12

When you have finished paying all the tithe of your increase in the third year, the year of tithing, then you shall give it to the Levite, to the stranger, to the orphan and to the widow, that they may eat in your towns and be satisfied.LXX Deut 26:12

When you have finished paying all the tithe of the produce of your land in the third year, you shall give the second tithe to the Levite...

Fig. 5.28: Guido Reni, “Moses with the Tables of the Law.” Galleria Borghese, Rome. 1624.

There are numerous examples like this spread throughout the legal texts in early Judaism. Early Christian Jews like Mark, Matthew and Paul express even greater shifts in legal and ethical thinking. In Mark 7, for instance, Jesus is portrayed quite radically when he challenges prevailing biblical dietary laws by pronouncing that all food is clean. In Matthew, one need not look any further than the sermon on the mount (chapter 5-7) to see legal and moral shifts, though they are not to the same degree as in Mark. In Paul’s rethinking about Judaism in Galatians, he radically calls for an abandonment of circumcision for Gentile converts to Christianity, which he regards as the fulfillment of Judaism and the culmination of Israel’s history.

This shift is particularly radical because it takes aim at Jewish identity as it is rooted in the establishment of a perennial covenant between God and Abraham, Israel’s founding patriarch. Genesis 17:14 uses the words of God to clearly establish the boundary that divides God’s people from the rest when it stipulates, “But an uncircumcised male who is not circumcised in the flesh of his foreskin, that person shall be cut off from his people; he has broken my covenant.”

5.3.2 Aggadah

Fig. 5.29: “Joseph and Aseneth” by an unknown artist. Staatliche Museen, Berlin, c. 1500. The apocryphal story of Joseph and Aseneth, found today in the OT Pseudepigrapha, is an aggadic midrash on Gen 41:45.

Aggadah (“narrative”)—sometimes called haggadah or aggidic midrash—likewise aims to make scripture relevant in new social contexts, but instead of addressing legal and moral issues it contemporizes scriptural narratives through legendary enlargements or even the rewriting of scripture itself in a kind of expanded paraphrase. In a sense, it engages in the retelling of biblical stories, events, or persons with a theological, ethical, or political aim. For example, the Testament of the Twelve Patriarchs (2nd - 1st century BCE) is regarded as a midrash on Genesis that intends to make the case for Levi as the ruling tribe during the reign of John Hyrcanus. Likewise, Jubilees (2nd century BCE) rewrites Genesis and Exodus as a protest against the Hasmonean princes. Joseph and Aseneth (1st century BCE – 2nd century CE) on the other hand, is a lengthy expansion on a single verse, explaining how it came to be that a righteous Israelite like Joseph could have ever married Aseneth, the daughter of Potiphera who was a pagan priest (Gen 41:45).

Fig. 5.30: Gioachino Assereto, “Isaac Blessing Jacob.” Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, c. 1643.

Examples also abound on a smaller scale where specific texts are newly explained. For instance, in contrast to Genesis, the writing called Wisdom (1st cent. BCE) represents Jacob as an innocent character when he fled after deceiving his brother over obtaining the blessing from Isaac. Wisdom 10:10 reads, “Wisdom rescued from troubles those who served her. When a righteous man fled from his brother’s wrath, she guided him on straight paths; she showed him the kingdom of God, and gave him knowledge of angels; she prospered him in his labors, and increased the fruit of his toil.” One of the tendencies in aggadic midrash is to cast characters from the distant biblical past in the role of saints. Especially helpful examples of aggadah are found in a version of the scriptures called the Targums (lit. “translations”), which were Aramaic paraphrases of the Hebrew scriptures written down as early as the second century CE. One such targumic expansion is Gen 22:10 which concerns the near sacrifice of Isaac by Abraham.

MT Gen 22:10

Abraham stretched out his hand and took the knife to slay his son.Targum Neofiti Gen 22:10

Abraham stretched out his hand and took the knife to slay his son Isaac. Isaac answered and said to his father Abraham: “Father, tie me well lest I kick you and your offering be rendered unfit and we be thrust down into the pit of destruction in the world to come.” The eyes of Abraham were on the eyes of Isaac and the eyes of Isaac were scanning the angels on high. Abraham did not see them. In that hour a Bath Qol [voice from heaven] came forth from the heavens and said: “Come, see two singular persons who are in my world; one slaughters and the other is being slaughtered. The one who slaughters does not hesitate and he who is being slaughtered stretches out his neck.” (Translation is from Martin McNamara, Targum Neofiti 1: Genesis.The Aramaic Bible 1A; Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 1992).

Many scholars have observed that some of the Gospel accounts are best explained as aggadic midrash as well. If we assume the common view that Matthew and Luke independently used Mark along with Q, then some of the changes in Matthew and Luke can potentially be midrashic. For instance, only Matthew and Luke contain the infancy accounts of Jesus. Though they differ in numerous places, they both extensively use scripture to theologically explain the meaning of Jesus’ humble birth for the good of humanity. At the other end of the story, the passion accounts in Matthew and Luke are much more extensive than that of Mark, again containing numerous scriptural citations and allusions that are used to explain the significance of Jesus’ suffering, death, and resurrection.

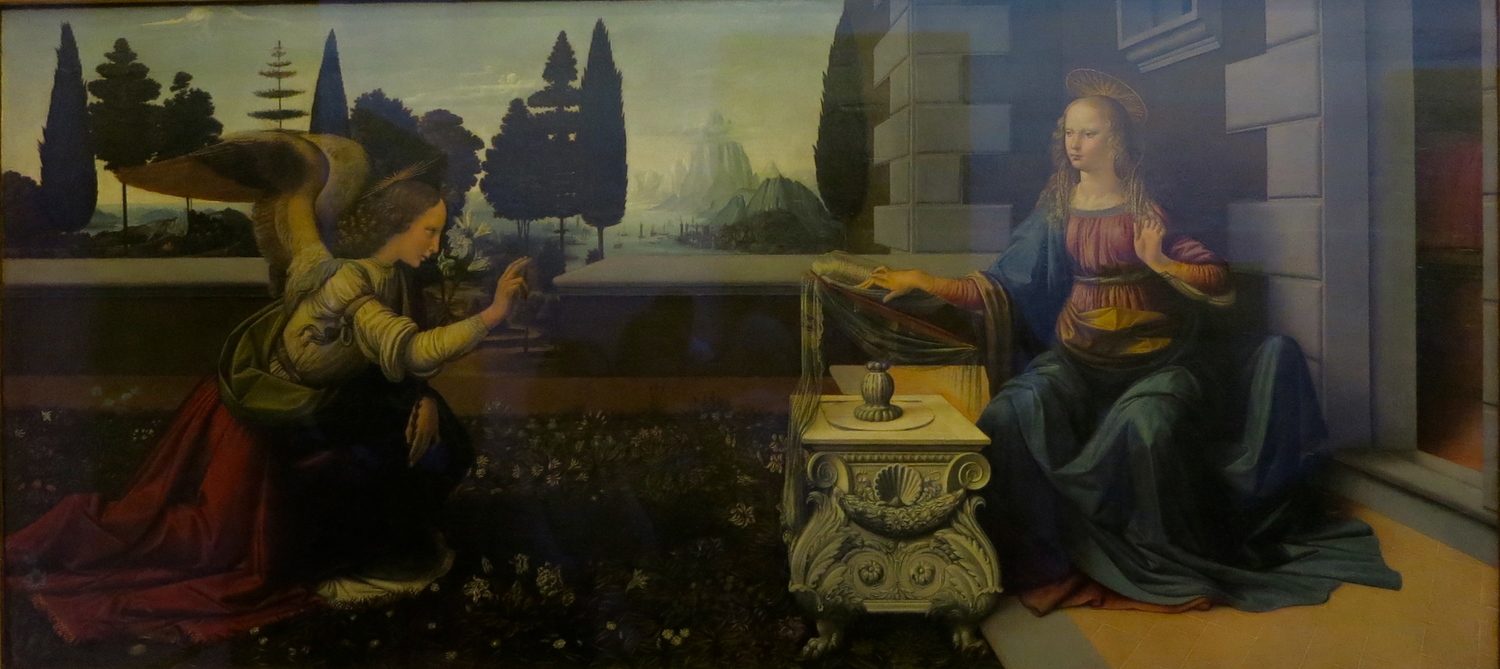

Fig. 5.31: Leonardo da Vinci, “The Annunciation” Uffizi, Florence. c. 1472.

When Matthew and Luke contain expansions (beyond Mark and Q) that include scriptural quotations or allusions, scholars debate the compositional sequence. Which came first in the composing of the Gospels, the quotation from scripture or the Gospel narrative that contains it? In other words, were some of the sections in the Gospels, like the infancy accounts and portions of the passion accounts, composed as enlargements of scripture or were the scripture texts embedded after the accounts were written? Some of the texts point more clearly in one direction instead of the other.

Fig. 5.32: Mosaic of the Lamb of God. Apse in the Basilica of Saints Cosmas and Damian. Rome. 7th century. The twelve Apostles are also depicted as sheep facing Jesus the Lamb.

For instance, John’s passion account probably reflects the former. Unlike the Synoptic tradition wherein Jesus dies on Passover, John has Jesus die on the day of preparation for Passover at the same time that the sacrificial animals were beginning to be slaughtered (18:28; 19:14). In addition, John connects Jesus’ death to the preparatory rules in Exodus. Commentators usually explain that the summary of Jesus’ execution in John 19:36 (“For these things came to pass to fulfill the Scripture, ‘no bone of his shall be broken’”) is taken from Exod 12:46 (“You shall not break any of its bones”) which is part of a list of regulations for the preparation of the paschal victim for the feast. For John, since Jesus was the Passover sacrifice, it is no surprise that in the narrative he should die at the same time as the sacrificial animals. John’s interpretation is not unique to early Christian thought. The same idea is found in Paul’s interpretation of Jesus’ death when he writes in 1 Cor 5:7 that “Christ our Passover also has been sacrificed.”

5.3.3 Pesher

A third common form of interpretation was called pesher (“meaning”). Unlike the seamless expansions and alterations of scripture in aggadah and halakhah, pesher distinguishes itself as an explicit commentary on scripture. This form of interpretation is commonly associated with the Essenes and their acpocalyptic belief in the imminent coming of God and the accompanying final battle between the righteous and the wicked—or as they sometimes put it, the “sons of light” and the “sons of darkness.” The primary aim of pesher was to show how scripture points prophetically to the end of the age—which coincidentally was the same period of history in which the Essenes believed themselves to be living.

Fig. 5.33: Ruins of an Essene settlement at Qumran, which was most likely destroyed by the Romans in 66-70 CE.

Pesher commentary operated from the perspective of two principles: (1) prophetic scripture refers to the end times, and (2) the present era is the end times. Thus, persons and events in the scriptures were connected, sometimes in an allegorical fashion, with persons and events contemporaneous with the Qumran community. Since Moses and David, for example, were prophetic figures for the Essenes, all of their teachings were ultimately directed at the Qumran community. The following example is typical. In a pesher on Habakkuk (1QpHab), the original lament and outrage by the prophet at the destruction caused by the Chaldeans is interpreted several centuries later by the Essene commentator as a lament and outrage directed at the Temple establishment. The reference to the Chaldeans becomes a code word for the Kittim—which many scholars understand as the Romans—who are viewed as the instruments of God’s judgment against the corrupt Temple leadership in Jerusalem. The square brackets below represent missing portions of the text in the manuscripts.

MT Hab. 1:4, 6

So the law becomes slack

and justice never prevails.

The wicked surround the righteous—

therefore judgment comes forth perverted…

For I am rousing the Chaldeans,

that fierce and impetuous nation,

who march through the breadth of the earth

to seize dwellings not their own.1QpHab 1:10-13

“Therefore Law declines, [and true judgment never comes forth” (Hab 1:4a). This means] that they rejected God’s Law [… “For the wicked man hems in] the righteous man” (Hab 1:4b). [The “wicked man” refers to the Wicked Priest, and “the righteous man”] is the Teacher of Righteousness.1QpHab 2:10-15

“For I am now about to raise up the Chaldeans, that br[utal and reckle]ss people” (Hab 1:6a). This refers to the Kittim, w[ho are] swift and mighty in war, annihilating [many people, and …] in the authority of the Kittim and [the wicked…] and have no faith in the laws of [God.

The New Testament writers were no strangers to pesher interpretation, but it is not used nearly as often as aggadah and halakhah. When it does occur, it tends more towards allegory. Unlike at Qumran where the fulfillment is found in the community itself, in early Christianity it is found in the person of Jesus, on the basis of whom the early Christian communities were formed. Paul’s interpretation of Deut 30:12-14 in Rom 10:6-8 is a case in point.

Deut 30:11-14

Surely, this commandment that I am commanding you today is not too hard for you, nor is it too far away. It is not in heaven, that you should say, “Who will go up to heaven for us, and get it for us so that we may hear it and observe it?” Neither is it beyond the sea, that you should say, “Who will cross to the other side of the sea for us, and get it for us so that we may hear it and observe it?” No, the word is very near to you; it is in your mouth and in your heart for you to observe (NRSV).Rom 10:5-9

Moses writes concerning the righteousness that comes from the law that “the person who does these things will live by them.” But the righteousness that comes from faith says, “Do not say in your heart, ‘Who will ascend into heaven?’” (that is, to bring Christ down) “or ‘Who will descend into the abyss?’” (that is, to bring Christ up from the dead). But what does it say? “The word is near you, on your lips and in your heart” (that is, the word of faith that we proclaim); because if you confess with your lips that Jesus is Lord and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved (NRSV).

Fig. 5.34: Hal Lindsey’s book, published in 1970, sold millions, beginning a modern kind of pesher reading of the Bible.

Today, pesher is alive and well. There is no shortage of doomsday prophets who read the Bible in light of the latest political headlines. Like their ancient counterparts, they believe that we are living in the last days and that the Bible contains numerous prophecies about our time. Those who have read Hal Lindsay’s bestseller The Late Great Planet Earth or watched the television evangelist Jack van Impe should find pesher sounding very familiar.

Midrashic interpretation in early Judaism and Christianity should not be thought of as simple exaggeration or misleading fabrication. While some of the expansions of scripture, especially in aggadic midrash, may well have been recognized as “stretches” of past stories especially among dissenting groups, they were by and large believed to be factual and meaningful. The use of the term “ancient fiction” also does not capture the midrashic aim, for fictional narratives in the ancient world were not versions of prior events or factual persons. The aim of midrash was simply to make scripture relevant to ever changing circumstances and culture. Since scripture was believed to be God’s word, it was able to address every new situation and was not tied to historical or literary contexts.

5.3.4 Christological Interpretation

Fig. 5.35: Fresco of Moses (or Peter) striking the rock in the wilderness, Catacombs of St Calixtus, Rome. 2nd-3rd century.

The most distinctive feature of early Christian interpretation of scripture was its Christological (i.e. Christ centered) focus. The basic early Christian assumption was that the Jewish scriptures pointed to, foretold, or in some sense illumined Jesus’ messianic identity, teachings, and actions. “Typology” is a term that is often used to capture the comparison between Jesus and prominent biblical characters and events. The general idea is that the biblical characters and events, which are said to be “types,” pre-figure or foreshadow the revelation of God in Christ, who is said to be the “archetype.” In their Old Testament context, the characters certainly are believed to reveal God, but the revelation comes to its fullness centuries later in Jesus. So, what God did in the past through figures like Moses, Israel, David, and the exodus, he does in the life of Jesus, though in a completed sense. Theological thinking at this point was not grounded in historical or literalist readings of scripture, but out of a concern for what those scriptures meant in light of the coming of Christ. The New Testament writings were written from the perspective of faith that was grounded in Christ, by people of faith, to people of faith, about faith.

Fig. 5.36: Ceiling fresco of scenes from the Jewish bible. Catacombs of Peter and Marcellinus, Rome. c. 300. For example, on the far left Jonah is being cast into the sea, and on the far right he is vomited out by the fish. The story of Jonah was often compared to Christ’s death and resurrection (as in Matt 16:4). Just under one hundred figures of Jonah have been found in early Christian catacombs and on sarcophagi dating prior to Constantine’s reign in the early part of the fourth century.

In addition to the numerous quotations and allusions from the scriptures in the New Testament, we are fortunate to have a few explicit references to their method, which has come to be called “Christological hermeneutics.” For example, in John’s Gospel, during an exchange with antagonistic Jewish religious leaders (called “the Jews”) Jesus validates his superior authority by claiming that the scriptures point to him. In 5:39 he tells the leaders, “You search the scriptures because you think that in them you have eternal life; it is these that testify about me.” Further in 5:46, Jesus reiterates, “For if you believed Moses, you would believe me, for he wrote about me.” These statements provide clear insight into how the Johannine Christians, who claimed to be guided by the Holy Spirit (John 14-16), appropriated scripture in the formation of their theological thinking.

Fig. 5.37: Duccio di Buoninsegna, “Road to Emmaus,” Museo dell’ Opera del Duomo, Siena. 1308-11.

Another window into early Christian interpretation is found in Luke’s story of the travelers on the Emmaus road and their encounter with the risen Christ. When Jesus is eventually recognized by the two travelers, the narrator summarizes, “Then beginning with Moses and with all the prophets, he explained to them the things concerning himself in all the scriptures” (Luke 24:27).

A third example is found in 1 Cor 15:3-4, which has often been regarded as part of a very early creedal statement. Here Paul connects the gospel of salvation from sin with the scriptures, which he understands to foreshadow or foretell the means through which the good news is accomplished, namely the death and resurrection of Jesus. He writes, “For I delivered to you as of first importance what I also received, that Christ died for our sins according to the scriptures, and that he was buried, and that he was raised on the third day according to the scriptures.” It is not at all clear to which text Paul is referring or whether he has in mind the entire biblical story, but it is unquestionably clear that the ultimate purpose of the scriptures is to convey that Jesus is the Christ.

Fig. 5.38: Hans Speckaert, Conversion of St. Paul, Musée du Louvre, Paris. 1577. Paul’s vision of Christ is told three times in the book of Acts (9:3-9; 22:6-11; 26:12-18), but it does not explicitly appear in his own letters. Some scholars, however, point to 1 Cor 15:3-8 and Gal 1:11-16.

It is important to notice that the earliest Christians were not concerned with literal interpretations or historical reconstructions of their scriptures, but with the way in which the scriptures provided meaning to a newly experienced spiritual reality. Scripture texts were frequently taken out of their original literary and historical contexts and read within a faith context that comprised of a history that had as its goal the salvation of humanity. At the centre of this understanding of history (often called “salvation history”) was the coming of Christ whose death and resurrection was believed to have restored the world. How the Christological hermeneutic came to be formed is a matter of anthropological and sociological debate, but phenomenologically—that is, via the testimony of experiences—early Christianity was founded on the claim that Jesus was raised from the dead. Claims of Christic visions and experiential encounters with the risen Christ in the post-biblical period abound, especially in the context of commemorative meals.

A deliberate separation between faith and historical fact, salvation history and history, theology and history, or faith and reason—as we have come to know these in the post-Enlightenment age—appear to have been nonexistent. If anything, theology and what we call history appear to have been unified in a way that the former gave direction to the latter. That which occurred in the past was divinely orchestrated to give shape and meaning to the present because it was believed that the purpose and goal of history has been revealed.

Try the Quiz

Bibliography

Translations of early Christian extracanonical texts:

Ehrman, Bart D. Lost Scriptures: Books that Did Not Make It into the New Testament. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Hennecke, Edgar and Wilhelm Schneemelcher, eds, New Testament Apocrypha. 2 Vols. Translation by R. McL. Wilson. Louisville: Westminster John Knox, revised edition 1991-2.

Robinson, James M. ed. The Nag Hammadi Library in English. New York: HarperCollins, 1990.

Secondary Sources

Argall, Randall A., Beverly Bow and Rodney A. Werline, eds. For a Later Generation: The Transformation of Tradition in Israel, Early Judaism, and Early Christianity. Harrisburg PA; Trinity Press International, 2000.

Baur, Ferdinand Christian. The Church History of the First Three Centuries. Translated by Allan Menzies. London: Williams and Norgate, 1878, 3rd ed. Original German publication in 1853.

Bauer, Walter. Orthodoxy and Heresy in Earliest Christianity. Edited by R. A. Kraft and G. Krodel. Philadelphia Seminar on Christian Origins. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1971.

Brown, Raymond E. The Community of the Beloved Disciple: The Life, Loves, and Hates of an Individual Church in New Testament Times. New York: Paulist Press, 1979.

Crossan. John Dominic. The Birth of Christianity: Discovering What Happened in the Years Immediately After the Execution of Jesus. New York: HarperCollins, 1998.

Depalma Digeser, Elizabeth. The Making of a Christian Empire: Lactantius and Rome. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2000.

Drake, Harold A. Constantine and the Bishops: The Politics of Intolerance. Ancient Society and History. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000.

Dunn, James D. G. Unity and Diversity in the New Testament: An Inquiry into the Character of Earliest Christianity. 2nd Edition. London: SCM Press, 1990.

Ehrman, Bart D. Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Evans, Craig A. Ancient Texts for New Testament Studies: A Guide to the Background Literature. Peabody: Hendrickson, 2005.

Juel, Donald. Messianic Exegesis: Christological Interpretation of the Old Testament in Early Christianity. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1988.

Koester, Helmut. “Apocryphal and Canonical Gospels.” Harvard Theological Review 73 (1980) 105-30.

Lapham, Fred. An Introduction to the New Testament Apocrypha. London: T. & T. Clark, 2003.

Longenecker, Richard N. Biblical Exegesis in the Apostolic Period. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1999.

Luz, Ulrich. Studies in Matthew. Translation by Rosemary Selle Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2005.

Kraemer, Ross and Mary Rose D’Angelo, eds. Women and Christian Origins. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Marjanen, Antii and Petri Luomanen, eds, A Companion to Second-Century Christian “Heretics.” Supplements to Vigiliae Christianae 76. Leiden: Brill, 2005.

Nickelsburg, George W. E. Ancient Judaism and Christian Origins: Diversity, Continuity, and Transformation. Minneapolis: Fortress, 2003.

Pagels, Elaine. Beyond Belief: The Secret Gospel of Thomas. New York: Random House, 2003.

–––––. The Gnostic Gospels. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1980.

Schüssler Fiorenza, Elisabeth. In Memory of Her: A Feminist Theological Reconstruction of Christian Origins. New York: Crossroad, 1983.

Stegemann, Ekkehard and Wolfgang. The Jesus Movement: A Social History of Its First Century. Translation by O. C. Dean, Jr.; Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1999.

Torjesen, Karen Jo. When Women Were Priests: Women’s Leadership in the Early Church and the Scandal of Their Subordination in the Rise of Christianity. San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1993.

![Fig. 5.25: Manuscript illumination of the Apostle John and Marcion of Sinope (according to R. Eisler, The Enigma of the Fourth Apostle [Methuen & Co., 1938, p. 158, plate XIII]). J. Pierpoint Morgan Library MS 748, folio 150 verso. 11th century.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d39a48e8593e000010788eb/1567165360066-XQ08JDPACFSDZVK1SZZE/Manuscript+illumination+of+the+Apostle+John+and+Marcion+of+Sinope.jpg)