Module Two

Social Context

2.1 Social Classes

Roman society across the empire can be divided into the elites and non-elites. The social distance between the two was enormous, and there was no middle class to speak of. Social migration from non-elite to elite was rare, since one’s birth determined status and there was very little opportunity for financial development. The stories of Jesus in the Gospels transcend the socio-economic boundaries. Whereas Luke tends to associate Jesus with non-elites, John connects him more with the elites. For example, in John, Jesus’ first miracle is on a prosperous estate in Cana. Another example is his close connection with the Beloved Disciple who seems to be well acquainted with Annas, the father-in-law of Caiaphas, the High Priest, who was surely an elite.

In addition to this most basic economic division, the first-century population can also be divided into citizens, slaves, and those who were simply called free peoples of the Empire, who were neither slaves nor citizens.

Fig. 2.1: Roman soldier with two slaves in neck collars. (Click the image to see the Ashmolean Museum where this relief is housed)

2.2 Elites

The elites were in the top three to five percent of the population in wealth, power, education, authority, and honour. Their value system was guided by personal gain and security, as opposed to the enhancement of the common good. Preservation of the political and economic status quo with its inherent social inequalities factored prominently in public policy. Although they showed disdain for manual labour, they depended on it for food, construction, and the trade of other goods and services. The elites were voracious consumers, living lavish lifestyles, exhibiting their status and wealth through clothing, jewelry, estates, exotic artifacts, entertainment, and meals.

Fig. 2.2: A floor mosaic in the home of an elite in Sepphoris.

The elites were the primary providers of employment, but exploitation of their laborers was rampant. In addition to profiting from the productivity of the laborers, the elites were ensured a constant cash flow from taxes and rents imposed on the non-elites. Since long term productivity was economically advantageous, the elites ensured that there was enough food distributed to the families of laborers during times of shortage. Jesus‘ parables in the Synoptic Gospels are firmly set within the socioeconomic matrix of the “haves” and “have nots.”

Fig. 2.3: House of a 1st century elite. Pompeii.

In most villages throughout the provinces, a group of men called “retainers” served as overseers for the elite and the government of Rome, and safeguarded the hierarchical system. They ensured that order and security were established and they served as liaisons to village elders who would have had most of the influence among local populations. The retainers, however, also interfered in long-established patterns of reciprocal trade among village households. These patterns, despite their benefit for the poor, were regarded as being economically counterproductive. In the new model, times of struggle were alleviated by a lightening of the tax load, reduction of debt, and even rent. Elites, through retainers, even sponsored village entertainment, communal events, and burial associations. The underlying purpose of patronage (or investment), however, was long-term productivity. Often patronages resulted in placing the villages further in debt.

2.3 Non-Elites

The non-elites, or peasants, can be categorized into levels of poverty. Some tradesmen earned enough to sufficiently provide for their families, while others barely scraped by, living in a state of perpetual near-starvation. Income from farming, too, fluctuated dramatically. Some seasons would have yielded enough to meet the needs of families, perhaps with some surplus, whereas other seasons would have been dire, especially if the elite withheld some of the supply to increase their own profitability.

2.3.1 Rural Peasants

Fig. 2.4: Palestinian farmer in the Battir hills (southwest of Jerusalem) working on his land in much the same way as first-century Jewish peasants.

In most Roman provinces, about ninety percent of the population lived in villages. The vast majority of these were peasants, which are not to be equated with the absolute poor. They were small farm owners and day laborers, working the land. The majority lived at a subsistence level, meaning that production was geared toward immediate consumption and allowed for very little (if any) surplus or disposable income. For peasant families, their plots of inherited land were their greatest possession, providing for their families’ sustenance and some degree of dignity in a society where the educated classes deemed the farmer as a necessary simpleton who had no impact on the cultural and political landscape. Hardships for these farmers were plentiful. Every year they risked losing crops due to floods, drought, or fire. When crops failed or farmers could not afford to pay taxes, they may have had to sell their land to opportunistic landowners or they may have even had to sell a child as a slave. Additional information about peasant farmers is found below under “Commerce”.

According to Josephus, the agrarian life was nowhere more concentrated than in Galilee. Despite his demographic and spatial exaggerations, Josephus’ description of Galilee, in contrast to commercial cities on the coast, is noteworthy. He writes,

These two Galilees, of so great largeness, and encompassed with so many nations of foreigners, have been always able to make a strong resistance on all occasions of war; for the Galileans are inured to war from their infancy, and have been always very numerous; nor hath the country been ever destitute of men of courage, or wanted a numerous set of them; for their soil is universally rich and fruitful, and full of the plantations of trees of all sorts, insomuch that it invites the most slothful to take pains in its cultivation, by its fruitfulness; accordingly, it is all cultivated by its inhabitants, and no part of it lies idle. Moreover, the cities lie here very thick, and the very many villages there are here are every where so full of people, by the richness of their soil, that the very least of them contain above fifteen thousand inhabitants (Jewish War 3.42-43).

The average life expectancy of peasants was between thirty and forty. By age thirty, most peasants had suffered from internal parasites, carried by livestock, rotting teeth, and bad eyesight. The archaeological evidence is sporadic, but still helpful. For example, fifty percent of the hair combs found at Masada, Murabba‘at and the Negev were infected with lice and lice eggs. There is also good reason to believe that malaria was a problem in the Sea of Galilee basin. For instance, Peter’s mother-in-law is described as suffering from a fever in Capernaum (Mark 1:30-31), and a centurion’s son also is said to have had a fever in the same city (Mark 4:52). These accounts come from an intensely malarious region, whereas towns like Nazareth and Cana were not situated in a valley, but atop a hill and therefore experienced fewer instances of this dreaded disease.

Infant mortality rates are estimated at thirty percent in many comparable peasant societies, often due to disease and malnutrition. In ancient Palestine, about sixty percent of those who survived their first year of life died by age sixteen, and in only a few families would both parents still be living when the youngest child reached puberty. Poor nutrition and illness was commonplace. Getting to a marriageable age for the peasant required overcoming pervasive health risks; thus most lives ended in premature death.

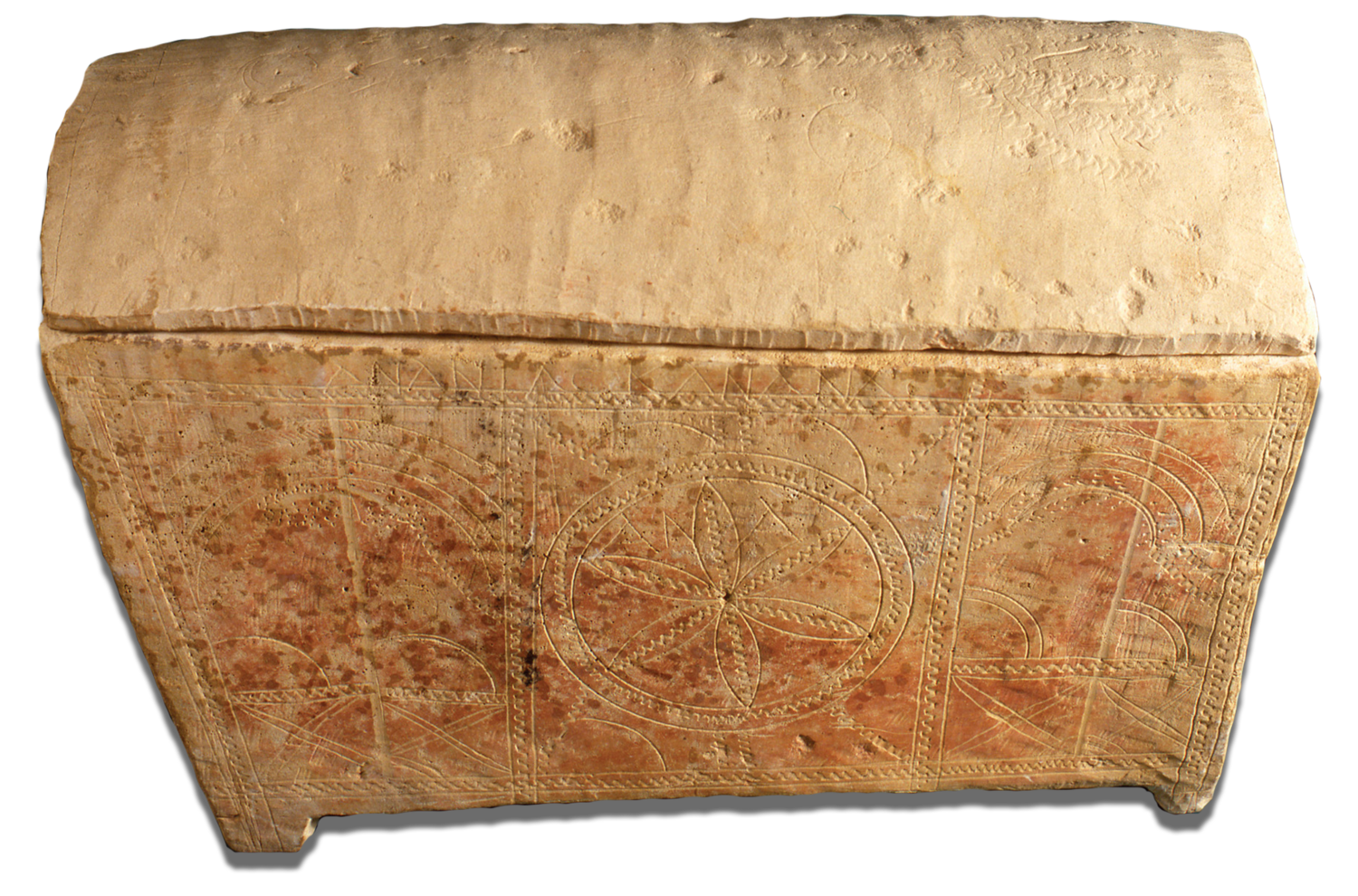

Fig. 2.5: A stone ossuary (bone-box).

2.3.2 Urban Peasants

In urban centers, peasants lived in deplorable conditions by today’s Western standards. Dwellings were often small, crowded, and unsanitary. Neighborhoods were dirty and smelled of human and animal excrement and garbage. Water was often contaminated. Refrigeration did not exist, though some dwellings did have crawl spaces that acted as coolers. Although there were shortages of food, some nonetheless did spoil and rot before it could be eaten. Urban life was replete with conditions that elevated the risk of infectious diseases.

Although social inferiority, exploitation, illness, and poverty characterized daily life, and status was accepted as fate, negative reactions by the peasant class is well documented. At times, protests were nonviolent, amounting to tax evasion, work slowdowns, desecration of Roman symbols, and vandalizing of the property of the elite. Often these actions were well calculated, so as to prevent the capture of the perpetrators.

The book of Revelation, in fact, can be viewed as a symbolic (and therefore disguised) protest letter in condemnation of Roman persecution. In this case the protest is ideological. The New Testament contains several subversive teachings directed at Rome, its system, its elite, and its sympathizers, such as the Jerusalem establishment. One well known ideological subversion is Jesus’ admonition, “render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s” in Matt 22:21/Luke 20:25. Historical Jesus scholars have argued that Jesus’ announcement of the kingdom of God should be understood as a subversive reaction to the kingdom of Caesar.

Fig. 2.6: The Flagellation of Our Lord Jesus Christ, by William-Adolphe Bourguereau (1880), Cathedral of La Rochelle, France.

Still other protests took the form of violent resistant movements. When taxation and debt reached a critical point, usually at the loss of family land, revolts sometimes took place against Roman occupation in the provinces. A number of violent uprisings against the Romans occurred from 4 BCE to 66 CE in Palestine, but each time the violence was short lived. Rome did not tolerate any kind of defiance, and dealt with it swiftly and aggressively. For deterrence purposes, perpetrators were punished publicly and harshly, including scourging and crucifixion. Although Jesus’ protest against social injustice was nonviolent, he was perceived as a messianic figure who posed a political threat and thus was subjected the same punishment.

2.4 Roman Citizens

The success of Roman expansion can be credited to its policy of incorporating conquered peoples into its empire. Instead of annihilating native populations, local political structures often remained in place, traditional cultural practices were encouraged, and grants of citizenship were offered to compliant groups and especially to wealthy/elite individuals in the provinces. The children of these new citizens would automatically inherit citizenship. The easiest way to become a citizen was to be born into it. Whether one was born into a Roman family or born in a foreign city whose residents were already granted citizenship, such citizenship was automatic. Paul likely received his citizenship in this latter manner, since the residents of his home city of Tarsus were granted citizenship decades before his birth. Children of freed slaves were also known to receive citizenship. Individuals were granted citizenship for a variety of services that benefited the empire. Usually these were granted by the Senate, a General in the field, or even the emperor himself.

Fig. 2.7: Household of an elite Roman citizen with slaves. Casa deli Amorini Dorati, Pompei. 1st century CE.

Household of an elite Roman citizen with slaves. Casa deli Amorini Dorati, Pompei. 1st century CE.

Citizenship had its benefits. Roman citizens could participate in the election of magistrates, had the right to be tried in Roman courts, had the right to appeal convictions, were exempt from personal tax, and (usually) could not be legally crucified, tortured, flogged, thrown to beasts, or sentenced to hard labor. Citizens could also serve in the Roman army, which provided a steady income, honour, and a pension that often included a residence in an outlying part of the empire, such as Philippi.

Perhaps the most well known Roman citizen in the New Testament is the apostle Paul, who at times appealed to his status for fairer legal treatment. At other times, however, Paul said nothing about his status, such as when he was imprisoned at Philippi. Why did Paul remain silent? Did he not have documentation with him? Or did he not want to be given special treatment while his fellow workers suffered? Appeals to citizenship required one to provide some kind of evidence. Travelers like Paul would usually carry their citizenship documentation with them, but in cases where the document could not be produced, the challenge to prove one’s citizenship could become a very difficult task. New documentation would have to be ordered from the applicant’s home region.

Fig. 2.8: “Paul Writing his Epistles” by Valentin de Boulogne (1620). Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

2.5 Slaves

The inhabitants of the empire can also be categorized into citizens, free people of the provinces, and slaves. Slavery was practiced throughout the Roman provinces and was culturally accepted. Slaves were the lowest class of people in Roman society. However, while slaves had very few rights, they were legally protected from gross mistreatment.

Seneca writes advice on the treatment of new slaves in his Essay About Anger 3.29.1–2:

It is base to hate a man who commands your praise, but how much baser to hate any one for the very reason that he deserves your pity. If a captive, suddenly reduced to servitude, still retains some traces of his freedom and does not run nimbly to mean and toilsome tasks, if sluggish from inaction he does not keep pace with the speed of his master's horse and carriage, if worn out by his daily vigils he yields to sleep, if when transferred to hard labour from service in the city with its many holidays he either refuses the toll of the farm or does not enter into it with energy - in such cases let us discriminate, asking whether he cannot or will not serve. We shall acquit many if we begin with discernment instead of with anger.

As Rome gained more ground, it gained more slaves. Some slaves were caught, bought and sold by slave traders; others were prisoners of war, such as those brought from Palestine after Rome’s conflicts with Jewish revolutionaries. Many were either born or adopted into slavery. Slavery was sometimes the fate of unwanted children (usually female) who were sold as a debt payment or given away or left to die because they were an economic liability for their parents. Some of these children were adopted and appropriated as personal property.

Slaves were valuable assets for the elite. Since they were property, they could be bought, sold, traded and inherited. To support this trade, slave markets were commonplace, especially in port cities.

Fig. 2.9: A mosaic from Carthage depicting a mistress and her slaves. Bardo Museum, Tunis. 3rd century CE.

The quantity of slaves one owned corresponded with one’s status. An elite master of high standing would have had slaves that numbered into the thousands. Pliny the Elder (23-79 CE) provides a summary of assets recorded in the will of a Gaius Caecilius Claudius Isidorus (who was probably at the upper end of the elite). Pliny writes that despite his losses in the civil war, Gaius left behind 4,116 slaves, 3,600 oxen, 257,000 head of other cattle, and 60,000,000 sesterces (Natural History 33.47).

Fig. 2.10: Floor mosaic of four slaves serving two masters in the middle. The two large figures are carrying wine. The figure on the far left is carrying water and towels. The figure on the far right is carrying flowers. Dougga, Tunisia, 2nd century CE.

It has been said that Rome was built on the back of its slaves. Though this is a highly simplistic statement, slavery certainly contributed to its growth. Slavery provided for inexpensive labor in a variety of areas, thus maximizing the profit margin for the owners and elevating lifestyles for both the elite and for some slaves; not all slaves were used for hard physical work. Most of the time they were used to perform household duties, such as cooking, cleaning, painting, building and host of physical tasks. Some were used as gladiators and others as prostitutes. A few slaves, however, had specialized skills and advanced education in medicine, philosophy, rhetoric and/or mathematics (such as the slaves that were brought from Greece when Rome defeated the Macedonians). These slaves performed more specialized duties which required literacy and writings skills, such as managing the financial affairs of their masters, recording business transactions in ledgers, teaching both the children and adults in their master’s household and looking after the medical well being of their owners.

There is no indication in the New Testament that the early Christians opposed slavery. There is no mandate for its abolishment or that it was considered morally reprehensible. Paul, who had direct contact with the runaway slave Onesimus simply encouraged him to return and reconcile with his master, Philemon. In 1 Cor 7:20-24 Paul indicates that freedom is the better option if it becomes available, but he tells slaves to be content in the condition they find themselves, since they are free in Christ.

2.6 Freedmen

When slaves were freed, they were known as freedmen. Some masters freed their slaves as acts of kindness. In some cases, this was requested in the master’s final will. Some masters freed their slaves by marrying them. Other slaves, who saved enough, requested to pay for their own liberty. This was known as a “ransom fee”—terminology used by Paul on occasion to explain liberation from the bondage of sin (e.g. 1 Cor 7:20-24).

Once freed, slaves were incorporated into the mainstream culture and given a qualified citizenship through the patronage of their masters. Male children of freedmen automatically qualified for unrestricted citizenship. The ancestral line of a freedman bore the name of the master or master’s family. A freed slave may have had an ongoing obligation to that family. For example, if the slave Onesimus was freed by his owner, Philemon, Onesimus would be known as “Philemon Onesimus.” The freedmen and his family also continued to worship the same deities as their former masters. This may explain how Onesimus became a Christian.

Fig. 2.11: Procession of the Imperial Family. Frieze from the Altar of Augustan peace commemorating Augustus’ campaigns against Spain and Gaul. Museum of the Ara Pacis, Rome, 13-9 BCE.

2.7 Family Life

Fig. 2.12: Fresco of a family banquet, Pompeii, 1st century CE. National Archaeological Museum, Naples.

The basic building block in Greco-Roman society was the family, highly valued by both Jews and gentiles. Unlike today’s Western societies, which can be classified as individualistic, first century society was collectivistic. Families included aunts, uncles, grandparents, cousins, and even included the extended families of the extended families. If the family was wealthy, their slaves were also included.

The most basic social unit in a traditional agrarian society, such as first-century Palestine, was the household family, which consisted of a husband, his wife, their children, the husband’s parents, and his brothers’ families. Sons generally stayed at home after marriage. Family ties, or “kinship,” shaped identity, political views, religion, vocation, and roles. Kinship networks played a key role in the arrangement of marriages, dowries, occupations, and economic wellbeing. The position of an individual within a kinship network helped define that person’s position in the broader community and largely determined one’s own identity and prescription for life. Gender, race, religion, and social status were prescribed identity boundaries which were rarely crossed.

2.7.1 Marriage

Fig. 2.13: Nuptial ceremony of the elite class. Frieze on the sarcophagus of the bridegroom. Ducal Palace, Mantua. Italy. 2nd century CE.

The importance of kinship and community was particularly noticeable in the institution of marriage. Almost everyone married at least once. Children were raised with a clearly established view of marriage and spousal roles. Women were usually married by their late teens. Men married slightly older. Marriage was not orchestrated or determined by individuals who entered into a romantic relationship. Instead, the entire family was involved in choosing and negotiating suitable marriage partnerships, often for pragmatic reasons. The preparations began with a betrothal period, which could last from a short time before a wedding, to years before the couple was eligible for marriage. During this time the dowry was set from the bride’s side, and goods and services were transferred from the groom’s family (e.g. Gen 34:12; m. Ket. 1.2; 5.1).

One of the ways in which property was retained in a kinship network was by marrying relatives, such as cousins. Incidences of endogamy (marriage between kinship group members) in the ancient world ranged from nineteen to sixty percent of all marriages. One of several examples from the Jewish scriptures is Abraham’s request that Isaac marry within their kinship group. Another example comes from Josephus, who writes that, of the eight generations of the Herodian family, twenty-two of the thirty-nine marriages mentioned were endogamous.

As with marriage, divorce was not an individual decision, but involved the two families, who were responsible for the repayment of dowries, redistribution of property, and settlement of other accounts. In practice, this was complicated by the fact that the husband controlled all of the property.

2.7.2 Men

The ancient Mediterranean world was patriarchal. In broader society, the father of the family (the most senior male) was known as the paterfamilias. He had absolute power over his entire household: wife, children, extended family, and slaves. He controlled the finances for the family, directed the religious life of the household and chose his children’s spouses. He even had the power to “expose” his newborn infants if they proved to be a financial liability. “Exposure” or “casting out” refers to abandoning infants in remote areas. Some would be picked up by slave owners, whereas others would be eaten by animals. We do not know how often this happened, but when it did, it usually did not affect the firstborn or boys. We have no record of Christians or Jews practicing the exposure of infants, nor any contemporary record of them speaking for or against it.

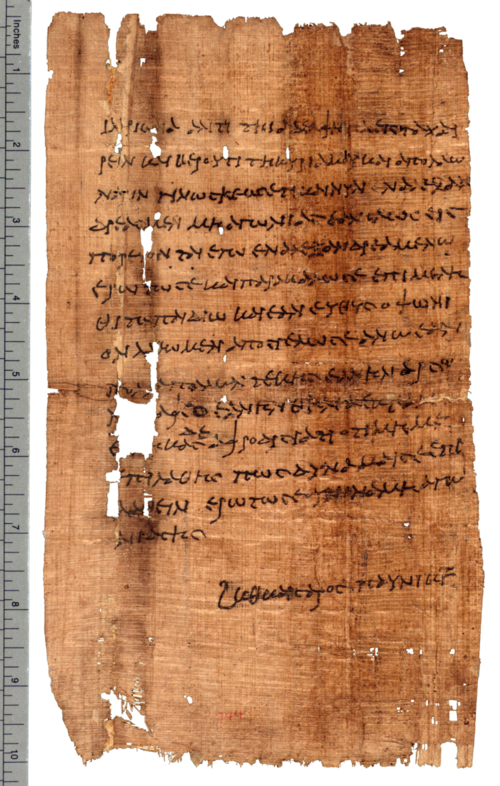

Fig. 2.14: Oxyrhynchus Papyrus (P. Oxy.) 4 744. Courtesy of Duke databank of documentary papyri.

The following quotation comes from a first-century (BCE) letter, discovered in Oxyrhinchus, Egypt. It conveys the father’s power and attitude about his unborn child. While away in Alexandria, Hilarion writes to his wife, Alis:

I beg and entreat you, take care of the little one, and as soon as we receive our pay I will send it up to you. If by chance you bear a child, if it is a boy, let it be, if it is a girl, cast it out” (P. Oxy. 4 744).

Note Ovid’s condemnation of self-administered abortions. Interestingly, the blame removes the man from the practice, which is another example of patriarchy.

Of what use is it for damsels to live at ease, exempt from war, and not with their bucklers, to have any inclination to follow the bloodstained troops; if, without warfare, they endure wounds from weapons of their own, and arm their imprudent hands for their own destruction? She who was the first to teach how to destroy the tender embryo, was deserving to perish by those arms of her own. That the stomach, forsooth, may be without the reproach of wrinkles, the sand must be lamentably strewed for this struggle of yours.

If the same custom had pleased the matrons of old, through such criminality mankind would have perished; and he would be required, who should again throw stones on the empty earth, for the second time the original of our kind. Who would have destroyed the resources of Priam, if Thetis, the Goddess of the waves, had refused to bear Achilles, her due burden? If Ilia had destroyed the twins in her swelling womb, the founder of the all-ruling City would have perished.

If Venus had laid violent hands on Æneas in her pregnant womb, the earth would have been destitute of its Cæsars. You, too, beauteous one, might have died at the moment you might have been born, if your mother had tried the same experiment which you have done. I, myself, though destined as I am, to die a more pleasing death by love, should have beheld no days, had my mother slain me.

Why do you deprive the loaded vine of its growing grapes? And why pluck the sour apples with relentless hand? When ripe, let them fall of their own accord; once put forth, let them grow. Life is no slight reward for a little waiting. Why pierce your own entrails, by applying instruments, and why give dreadful poisons to the yet unborn? People blame the Colchian damsel, stained with the blood of her sons; and they grieve for Itys, Slaughtered by his own mother. Each mother was cruel; but each, for sad reasons, took vengeance on her husband, by shedding their common blood. Tell me what Tereus, or what Jason excites you to pierce your body with an anxious hand?

This neither the tigers do in their Armenian dens, nor does the lioness dare to destroy an offspring of her own. But, delicate females do this, not, however, with impunity; many a time does she die herself, who kills her offspring in the womb. She dies herself, and, with her loosened hair, is borne upon the bier; and those whoever only catch a sight of her, cry "She deserved it.” But let these words vanish in the air of the heavens, and may there be no weight in these presages of mine. Ye forgiving Deities, allow her this once to do wrong with safety to herself; that is enough; let a second transgression bring its own punishment (Ovid, Loves 2.14.27-38).

Likewise in Jewish households, men were the heads. They attended to most of the work in the fields (except at harvest when all the family members participated), worked in trades, trained their sons, interacted with other household heads, and made important family decisions.

The eldest son became the head of the family and bore the responsibility to ancestors and descendants. Perpetuation of the family unit through marriage ensured the inheritance and continued maintenance of the family land, always under male control. Inheritance was not equally distributed. According to biblical law codes (Deut 21:17), the eldest son would inherit twice that of any brother.

Fig. 2.15: Rembrandt van Rijn, “Return of the Prodigal Son,” c. 1661-69. Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg.

The privileged status (and the elevated responsibilities) of the first-born son in ancient Mediterranean culture provides an important exegetical background for the parable of the Prodigal Son (Luke 15:11-32) and the Parable of Wicked Tenants (Mark 12:1-11) and several Christological images and titles in the New Testament, such as “son of God”.

The male/female divide was rationalized partly along biological lines and partly along theological lines. It seemed reasonable that since the father produced the seed from which the child was born (Wis 7:1-2) and the mother merely supplied a womb, a privileged status was assumed for the male as the sole procreator of children—the provider of life. It was also argued that since God created man before the woman, and the woman from the bone of the man (Gen 2:7-23; 1 Cor 11:7-9), the man was regarded as having the dominant position.

2.7.3 Women

In Roman society, each wife was expected to obey her husband, serve his interests, raise his children, worship his gods, and manage his household(s). Managing the household was no small task in elite families, and allowed some women to wield significant power. Women were obligated by law to remain faithful to their husbands; whereas husbands were afforded latitude to satisfy their sexual desires outside the marriage. When a woman married, she passed from being under her father’s control to being under her husband’s. In many cases wives were confined to their own area of the house, which was designated as the “women’s quarters.” Female subordination may have been influenced in part by traditional Greek thinking, which saw the female as an undeveloped male.

With regard to female liberty, the Roman historian Livy (c. 59 BCE - 17 CE) writes, “Never, while their men survive, is feminine subjection shaken off; and they themselves abhor the freedom which the loss of husbands and fathers produces” (History of Rome 34.1.12).

However, by the first century CE, women in Roman society were becoming more autonomous. They were gaining, more liberty, power, influence, and a higher legal status. One of the reasons for progress was necessity. Since Rome’s political conflicts and peace-making ventures throughout the empire took a toll on the male population in Rome, many women were left to fend for themselves. These women would eventually become more socially self-determined and visible in financial and political affairs. The same kind of progress was usually not seen outside of Rome.

Fig. 2.16: This figure of a woman holding a pen and codex (book) implies literacy among at least some of the Roman women. Pompeii, 1st century CE. National Archaeological Museum, Naples.

Like today, women were greatly appreciated in many households. The following quote from a tombstone reflects a common view of womanly virtues. “This is the unlovely tomb of a lovely woman. Her parents named her Claudia. She loved her husband with her whole heart. She bore two sons.… She was charming in conversation, yet her conduct was appropriate. She kept house, she made wool” (from Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum1.2.1211).

Fig. 2.17: Fayum mummy portrait of an adorned woman, Egypt, late 1st century. Walters Art Museum, Baltimore.

Some Jewish texts did not portray women in a flattering manner: they were perceived as inherently sinful (Philo, Hypothetica 11:14-17; Sir 42:12-14) and potentially dangerous (Philo, Virtues 38-40). Other texts advocated respect and honour for their roles as wives, mothers, and teachers in the home (Prov 1:8; 6:20; 31:10-31). A woman’s primary value lay in her ability to give birth, raise children, and take care of the domestic duties. According to some Jewish texts, marketplaces, council chambers, and courts of justice were viewed as more suitable for men; whereas, informal household management was for women (Philo, Special Laws 3.169-71; see also Flaccus 89). In Jewish society, women were restricted from many religious duties. They were not regarded as trustworthy witnesses in court proceedings. The standard prayer in the rabbinic prayer book did not help their cause either: “Blessed art thou O Lord our God, who has not made me a woman.” Although this prayer should be viewed in the context of male responsibility and honour to fulfill the whole law, it was nonetheless patriarchal. In the home, women prepared the meals, washed clothes, made clothing, cleaned the house, and raised the children. However, when the crops were ready to be harvested, the division of labour was not so rigid. Both men and women worked in the fields.

On the character of women from a first century BCE Jewish writing:

For evil are women, my children; and since they have no power or strength over man, they use wiles by outward attractions, that they may draw him to themselves. And whom they cannot bewitch by outward attractions, him they overcome by craft. For moreover, concerning them, the angel of the Lord told me, and taught me, that women are overcome by the spirit of fornication more than men, and in their heart they plot against men; and by means of their adornment they deceive first their minds, and by the glance of the eye instill the poison, and then through the accomplished act they take them captive. For a woman cannot force a man openly, but by a harlot’s bearing she beguiles him. Flee, therefore, fornication, my children, and command your wives and your daughters, that they adorn not their heads and faces to deceive the mind: because every woman who useth these wiles hath been reserved for eternal punishment. For thus they allured the Watchers who were before the flood; for as these continually beheld them, they lusted after them, and they conceived the act in their mind; for they changed themselves into the shape of men, and appeared to them when they were with their husbands. And the women lusting in their minds after their forms, gave birth to giants, for the Watchers appeared to them as reaching even unto heaven (Testament of Reuben 5:1-7).

Daughters were valued less than sons. Several rabbinic texts speak of an elevated rejoicing at the birth of a son in contrast to the birth of a daughter. In dire economic circumstances when families had to provide a debt-slave to a landowner, daughters were the first to go, since sons were needed to maintain the family line and to do manual work. According to marriage contracts, a daughter’s value was primarily based on her potential fertility. A dowry would have been an economic liability, especially since its size displayed a family’s honour. By twelve and a half, the father could transfer dominion over his daughter to the betrothed and his family. After the marriage, her husband could maintain patriarchal control over his wife for the rest of their lives. All of her economic assets, such as an inheritance, were transferred at the discretion of the husband. The popular perception of daughters in early Judaism is well expressed in the proverbs of Sirach 42:9-14.

2.7.4 Women in Early Christianity

Early Christian perspectives on women are sometimes criticized as being misogynist. Paul is grilled for his negative comments about women—that they should keep silent in the churches, attend only to household duties, be submissive to their husbands, not teach men and learn from their husbands (e.g. 1 Tim 5:14; Titus 2:3-5). However, like us, Paul is a child of his time, influenced by the dominant culture. One of the most hotly debated issues in the study of Paul and his letters is his view on the religious roles of women. At first glance, the evidence seems to go in opposite directions.

On the one hand there is no question that women played an important, even prominent, role in the early Christian communities. In Romans 16 Paul greets Phoebe who was both a deacon and his patron. He greets Prisca and her husband Aquila and thanks them for risking their lives for the gentile mission. Placing Prisca before her husband suggests prominence. He greets Mary, who works among the Romans. The most interesting in this long list is his greeting to Junia (along with Andronicus) in v.7, whom he calls “prominent among the apostles.” He greets other female fellow workers, named Tryphaena, Tryphosa, and Persis. He concludes his greeting by including Julia, the mother of Rufus, and the sister of Nereus. The list of women who are greeted and praised for their faith, service, and leadership in the fledgling church communities extends to Corinthians and Philippians. In Gal 3:27-28, Paul makes what appears to be a counter cultural pronouncement that there is no longer Jew or Greek, slave or free, and male or female, since all are one in Christ. It is difficult, though, to say that Paul intended equality on every social level.

Fig. 2.18: Fresco from the Catacomb of Priscilla, Rome. 2nd-3rd century CE. In this depiction of the Eucharist, the participants may well be women, which would have been contrary to view of many Church Fathers.

In other parts of the New Testament, women also take on prominent positions. Luke’s gospel is particularly positive on the role of women. For example, at the beginning of the gospel, women prophesy about the coming of a saviour. It is Mary, also, who prays the first gospel message in the Magnificat (1:46-55), and is chosen to be the one through whom salvation comes into the world. At the end of Luke, it is the band of women who come to anoint Jesus’ body that are privy to the first announcement of the good news that Jesus has risen from the dead. It is also these women (Mary Magdalene, Joanna, Mary the mother of James, and the other women) who then preach the good news to the apostles, though it falls on deaf ears (24:10). Positions of prominence among women continued well into the second century, but primarily among Gnostic Christians. By the end of the first century, as more mainstream Christianity became institutional, leadership positions were held almost exclusively by men.

Though this was not the case everywhere. In a letter to the Emperor Trajan, Pliny to the Younger, Governor of Bithynia (111-113 CE), seeks advice on how to legally treat Christians, since they were neither paying homage to the emperor, nor buying goods for sacrificial rituals. Perplexed by the spread of this new religion, Pliny begins to interrogate Christians. At one point he targets female deacons.

It is customary for me, sir, to refer to you in all matters wherein I have a doubt. Who truly is better able to rule my hesitancy, or to instruct my ignorance? I was never present at examinations of Christians, therefore I do not know what is customarily punished, nor to what extent, nor how far to take the investigation. I was quite undecided; should there be any consideration given to age; are those who are however delicate no different from the stronger? Should penitence obtain pardon; or, as has been the case particularly with Christians, to desist makes no difference? Should the name itself be punished (even if crimes are absent), or the crimes that go with the name….

They asserted, however, that the sum and substance of their fault or error had been that they were accustomed to meet on a fixed day before dawn and sing responsively a hymn to Christ as to a god, and to bind themselves by oath, not to some crime, but not to commit fraud, theft, or adultery, not falsify their trust, nor to refuse to return a trust when called upon to do so. When this was over, it was their custom to depart and to assemble again to partake of food--but ordinary and innocent food. Even this, they affirmed, they had ceased to do after my edict by which, in accordance with your instructions, I had forbidden political associations. Accordingly, I judged it all the more necessary to find out what the truth was by torturing two female slaves who were called deaconesses. But I discovered nothing else but depraved, excessive superstition (Pliny, Letter to Trajan).

Fig. 2.19: Fresco of Paul and Thecla near Ephesus, 6th century CE. Both are portrayed as equals. Probably influenced by a the 2nd century writing Acts of Thecla, they share the same height and teaching posture, but Thecla’s eyes and hand are disfigured, while Paul’s is left intact. The vandalism may indicate opposition to the teaching role of women.

On the other hand, there are several references in Pauline letters that can be taken as negative characterizations of women. We read that women are to be subordinate to men, forbidding them to take on leadership positions in the church, and not allowing them to teach men. We find these sentiments primarily expressed in the Pastoral letters (1, 2 Timothy, Titus), written to pastors Timothy and Titus who were to appoint only male leaders meeting specific criteria, such as having wives who were submissive (e.g. 1 Tim 2:4, 11-13; 3:2-5, 12; 4:7). The root of this view may be found in the retelling of human creation in 1 Tim 2:14, which identifies Eve (and hence female nature) as the transgressor and deceiver of men, since she was the one who was deceived by Satan. So why is the portrayal of women so different in the Pastoral letters? Some scholars reason that the Pastorals were not written by Paul, but by his followers several decades after his death. The arguments for this view is too vast to discuss at this point, but is summarized below in the chapter on the Pastoral letters. Other scholars argue that since very similar stipulations against women are found in 1 Cor 14:34-35, an undisputed Pauline letter, Paul’s negative views about the role of women in the church are directed at specific individuals who are disrupting their congregations.

2.7.5 Children

Children were expected to respect and honor their parents, and their elders in society. Special honor was due to the child’s father. It was sometimes said that the child should honor and obey one’s father as if he were a god. Fathers were expected to discipline their children not only to teach them to be good members of the society, but also for the sake of the family’s honor. A wayward or undisciplined child brought shame and dishonor upon the family. In turn the family’s reputation would affect broader relationships, social standing, and even economic wellbeing. Discipline was believed to be a cure and a preventative measure against any actions that could potentially hurt the family. A proverb from Sirach 22:3 is illuminating: “It is a disgrace to be the father of an undisciplined son, and the birth of a daughter is a loss.” Fathers tended to be harsh in disciplinary action in comparison to mothers, who tended to be tender toward their children. Fathers usually taught their sons the family trade; whereas mothers would educate their daughters in domestic skills and moral development. Sons were often expected to be obligatory to their fathers even after they were married.

This is Seneca on the treatment of children:

Do you not see how fathers show their love in one way, and mothers in another? The father orders his children to be aroused from sleep in order that they may start early upon their pursuits, - even on holidays he does not permit them to be idle, and he draws from them sweat and sometimes tears. But the mother fondles them in her lap, wishes to keep them out of the sun, wishes them never to be unhappy, never to cry, never to toil (Essay About Providence 2.5).

Consider also these early Jewish Proverbs from the second century BCE:

He who loves his son will whip him often,

so that he may rejoice at the way he turns out.

Pamper a child, and he will terrorize you;

play with him, and he will grieve you.

Give him no freedom in his youth,

and do not ignore his errors.

Bow down his neck in his youth,

and beat his sides while he is young,

or else he will become stubborn and disobey you,

and you will have sorrow of soul from him

(Sirach 30.1,9, 11-12).

2.8 Honor and Shame

In the ancient world, honor and shame penetrated the very fabric of society, from the individual to the community. Some historians have called honor the most important identity trait that an individual or a family could achieve, and conversely, shame was the worst. Since one’s identity was dependent on what others in the community thought about you—called a dyadic personality, it was vital that one be regarded as an honorable person. The individual’s self-assessment played no role in forming identity and self worth. The reputations associated with either shame or honor affected almost every area of life because it determined one’s inclusion or exclusion within the community. Given the importance of honor, people’s primary motivation in every aspect of daily life was to avoid shame.

For Romans, and for many subjects of the empire, honor was inherited by means of one’s ancestry, gender, citizenship, and marriage. But it could also be acquired through heroism in battle, political achievements, and usually through honest business interaction within society.

One of the few ways in which peasants could earn honor was by fostering a relationship with a patron. A person would approach a patron to become a client, which is a legally binding relationship. The patron would provide the client, and his family members, with legal aid, protection, healthcare, rewards, and even invitations to banquets. Whereas the client would offer services, public cooperation, and political cooperation by voting the way their patron voted. The patron’s honor was greatly enhanced by having clients, and the higher the status of the clients the higher the status of the patron. The patron might even be the client of a patron of a higher social class. The greatest of the patrons in the Roman world was the emperor.

Note Cicero’s (106-43 BCE) comments on Client-Patron Relationships:

Men of the lower orders have only one opportunity of deserving kindness at the hands of our order, or of requiting services,—namely, this one attention of escorting us when we are candidates for offices. For it is neither possible, nor ought we or the Roman knights to require them to escort the candidates to whom they are attached for whole days together; but if our house is frequented by them, if we are sometimes escorted to the forum, if we are honoured by their attendance for the distance of one piazza, we then appear to be treated with all due observance and respect; and those are the attentions of our poorer friends who are not hindered by business, of whom numbers are not wont to desert virtuous and beneficent men. [71] Do not then, O Cato, deprive the lower class of men of this power of showing their dutiful feelings; allow these men, who hope for everything from us, to have something also themselves, which they may be able to give us. If they have nothing beyond their own vote, that is but little; since they have no interest which they can exert in the votes of others. They themselves, as they are accustomed to say, cannot plead for us, cannot go bail for us, cannot invite us to their houses; but they ask all these things of us, and do not think that they can requite the services which they receive from us by anything but by their attentions of this sort (For Lucius Murena 34).

Among the elite, honor was achieved by financing public building, roads, and entertainment events. Financiers were then rewarded with public proclamations, inscriptions, and statues that acknowledged their honor publicly for a long time to come. For the ambitious, such honor was indispensable for achieving high political status and office.

The achievement and retention of honor could be accomplished through boasting, which was an accepted and required behavior. By contrast, humility was a sign of weakness. Honor was almost viewed like a commodity that was bought, sold, or exchanged in the market. Usually one’s gain of honor, however small, resulted in someone else’s loss of honor. Consequently, this led to a competitive culture that could be experienced even at the level of one’s family and close friends. From this perspective, Paul’s defence of his apostleship in 2 Corinthians takes on a social dimension which is otherwise missed.

In Jewish circles, honor included appropriate religious practice. Honor was achieved by being a good upstanding community member who upholds covenant obligations, such as the giving of charity to the poor, modest dress, participation in the religious life of the community, and, of course, obedience to the legal requirements, such as dietary restrictions, keeping the Sabbath, circumcision, and the giving of religious offerings.

Fig. 2.20: Lararium (household shrine) with tutelary deities and a guardian serpent. In the centre is the family Genius, which was the family deity. Tutelary deities were patrons and protectors of a particular place or person.

In the ancient world of the Mediterranean, the competition for honor was immense. There was only so much honor to be had. If one person lost some, then someone else grabbed it. If one person gained some via a promotion, a new business venture, then someone lost out. Even the giving of a gift was, in some way, seen as an opportunity to lose honor - for if one could not return the favour in equal measure dishonor resulted. However, if one refused the gift, then one insulted the honor of the giver. This could lead to vengeance through the defamation of character.

2.9 The Legal System

The legal system in first century Palestine was not founded on equality. A person’s status as freedman or slave, citizen or foreigner, child or adult, and male or female determined their legal rights.

Civil justice in Palestine during the reign of Herod and his sons was not based on Roman law, but was under the jurisprudence of the client rulers, who administered the province to meet the objectives set by Rome. Herod used three ruling bodies: the boule, the ekklesia, and the synedrion.

Boule – City Council

Fig. 2.21: Davide Ghirlandaio (1452-1525), Dead Christ Supported by the Virgin, St. John the Evangelist, and Joseph of Arimathea. Pinacothèque de Paris.

The boule was the city council (mentioned in Ant. 20.11; War 2, 331, 405; Dio Cassius,Historia 66, 6.2; Luke 23:50) of Jerusalem. This governing organization consisted of several hundred members that met to discuss matters dealing with the economy, such as setting market prices, certifying and providing weights and measures, and ensuring the purchase of wheat and supplies, which was always a concern in overpopulated areas. The city of Jerusalem also required magistrates who were responsible for the theatre and its water system—which Herod installed—and public health, including urban disposal and hygiene. It seems that the boule was called to decide or ratify decisions concerning civic legislation. In the New Testament Joseph of Arimathea (Mark 15:43; Luke 23:50) was most likely a member of this council.

Ekklesia – Popular Assembly

The popular assembly, ekklesia, had no real decision-making power, but enabled Herod to sense the mood of the people concerning his policies, and in turn allowed the population to believe that they were partners in important decisions. For example, Herod called together an assembly of the masses for their input on the building of the Temple (Ant. 15.381). Josephus also refers to a popular assembly that acted as an informal judge, jury, and executioner (Ant. 16.393-94; War 1.648-650). This public body consisted of priests and laymen, free men of military age, and convened whenever a need arose. It is probable that after Herod’s death, when Judea was ruled by Roman magistrates, the ekklesia was replaced by the Sadducees and the Herodian upper classes.

Synedrion - Sanhedrin

The synedrion (Sanhedrin) appears to have been created during the Herodian era, probably as a reconstruction of the Council of Elders during the Hasmonean period. It is not clear who served on this body, how it was structured, or who convened over its assembly. Its function, however, is clearer. It was the supreme legislative body that ruled on all legal matters that affected Jewish law, including criminal cases. The Sanhedrin could punish convicted offenders, but it is unclear whether it had the authority to enact capital punishment without Roman oversight. It appears that at times Roman governors intervened in local Jewish affairs and at other times they did not. In any case, the Roman authorities could take initiative themselves, without the approval of the Jewish court, and bring to trial anyone suspected of a political offence.

Fig. 2.22: Duccio di Buoninsegna, Christ Before Caiaphas and members of the Sanhedrin (1311). Museo dell’ Opera del Duomo, Florence.

After 70 CE, the Gospels tell the story of Jesus’ trial before a supreme religious court (Mark 14:53, 55, 64; Matt 26:57,59), and indicate that the Jewish and Roman jurisdictions worked together when cases overlapped. The story of Jesus’ trial, however, is hotly debated today, with some arguing that the Gospel writers told the story from an anti-Jewish establishment perspective, and in essence placed blame on the Temple elite. Although there are several examples of early Christians being tried before a Jewish religious court, without any interference by the Roman officials (Acts 4:1-22; 5: 17-42; 6:8-7:59; 22:5, 30), several Lukan scholars have well argued that the book of Acts tends to portray Rome as having significant oversight with favourable tendencies toward Christians.

Local Magistrates

There were other Jewish courts in addition to the Sanhedrin. At the community level, the judicial system was governed by local officials who appointed magistrates in villages throughout Galilee and Judea (Matt 5:22, 25; John 7:51). This informal system of local governments was independent of central authority, such as the Sanhedrin, and functioned much as it had done for centuries. The judiciary depended on seven elders, who had experience, wealth or power in a community, and whose main task was to settle legal cases. Josephus states that two Levites had to be appointed by the local village courts, and serve together with the seven judges (Ant. 4. 214; Matt 5:25). If expertise was needed, it is conceivable, that other Levites, priests, and scribes were available for consultation (Mark 3:22; Matt 9:3; Luke 11:45), with difficult cases being referred to a regional council (Acts 4:5; Josephus, Life 79). Decisions and punishments could be meted out according to Jewish law by local officials, which could include flogging (Matt 10:16-18), excommunication (Luke 6:22), or restitution (Matt 18:23).

2.10 Punishments

Punishments across the empire varied. Regional magistrates had great latitude and discretion in determining which punishment fit the crime. Thus, punishments were not always consistent. Sentencing was not only determined by the nature of the crime, but the extenuating circumstances, intentionality, reputation of the accused, and even the mood of the magistrate.

Before trials, it was not uncommon for suspects to be imprisoned and beaten with whips as part of the preliminary examination. Imprisonment was rarely considered punishment in the Roman world. Prisons served merely as holding tanks prior to sentencing. Though long incarceration in the form of exile to an island or remote city, usually for life, was reserved for the upper classes.

Fig. 2.23: Replica of Roman flagrum or flagellum. 1st century.

For the non-elite, a lenient penalty was a fine. For more serious crimes, the convicted party may have been sold as a slave, sentenced to lifelong manual labor in the mines, or condemned to the gladiator circuit. Prior to serving out their punishments, prisoners were sometimes beaten with a flagellum, which was made out of strands of leather with pieces of bone or metal on the ends.

Capital punishment took various forms depending on the crime. There was no shortage of Roman creativity and cruelty. In Rome, a murderer of a parent or relative was sewn into a sack and thrown into a river. A vestal virgin who broke her religious vow was buried alive. Some convicts were thrown to their deaths off the Tarpeian Rock, which was a steep cliff overlooking the Roman Forum. Distinguished Romans or elite prisoners of war were either strangled in prison or were given a dagger and asked to take their own life. There are records of prisoners being tied to a stake naked, whipped with a sack of rocks, and then beheaded. After the great fire in Rome, Nero accused Christians of arson and had a number of them arrested and burned alive on poles that lined the main road. A number of prisoners of war were also killed for entertainment in the Coliseum and other such venues.

Fig. 2.24: Heel bone of a crucifixion victim with an 11.4 cm nail, discovered in an ossuary found in a burial cave at Giv’at ha Mivtar, near Jerusalem. The name Yehochanan (John) is inscribed on the ossuary. 1st century CE. Courtesy Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

The most well known form of capital punishment practiced by the Romans was crucifixion. The remembrance of Jesus’ crucifixion has endured in the primary Christian symbols of the crucifix and the empty cross. Crucifixion was usually reserved for particularly vicious prisoners of war and insurrectionists, that is, violent opponents of Roman rule. After a beating, the victim was nailed to the cross through the wrists and feet. The weight of the body was supported by the nails. When the victim needed to breath, he raised himself up in excruciating pain. Muscles would spasm and cramp. Over time, insects and birds began to feed on the still live victim. Death usually came through gradual suffocation or shock. Sometimes the legs of the victim were broken to hasten death. The point of public crucifixion, which was not original to the Romans, was deterrence. It sent a clear message to anyone who thought of taking on Roman rule. After its use for almost a thousand years, the practice was eventually abolished in the fourth century under Emperor Constantine.

2.11 Commerce

Fig. 2.25: Temple of Castor and Pollux, who were twin sons of Zeus. Roma.

During Augustus’ reign the population of Rome numbered about one million, which was a powerful consumer body. An estimated thirty percent were slaves. No other city in the western world would reach this size until London in the eighteenth century. Rome’s growth to such an enormous size can be credited to its dependence on the resources of the provinces. Chief among these was its vast supply and trade of food. Rome alone consumed about sixty percent of the empire’s resources.

2.11.1 Macro-Scale Economics

Fig. 2.26: Wall painting of food produce at a thermopolium (hot food bar), Ostia Antica, Italy. 1st century CE.

As an agrarian society, Rome’s wealth and power was tied to its land. Much of the land in Italy and adjacent provinces that was economically viable was owned by the Roman elite and aristocracy, and often managed by tenant farmers. Provincial labor was cheap and often exploited through the use of slaves. The owners did not only profit from the agriculture itself, but also from rents and taxes (for consumption, production, and distribution) imposed on tenant farmers. Trade with distant lands that were in the empire, such as Spain and Egypt, were encouraged through tax breaks, subsidies for transportation, and offers of citizenship. Among the provinces, the elite also imported vast amounts of food, textiles, and building supplies in order to raise the profile and economy of their own beloved cities. Provincial elites in port cites, namely in Spain, Greece, Asia Minor, Palestine, and Egypt, had amassed great wealth, some of which through shipping. Often these cities were gateways to broader markets. Every port city would have employed vast numbers of people from ship hands and dock workers to financial officials and Roman administrators who oversaw the entire transportation process and even the storage facilities, especially for grain. Thousands of workers were also employed in ancillary industries, such as warehousing, operation of presses, making amphorae (ceramic storage jars), and shipbuilding and maintenance. In short, with an estimated population of sixty to seventy million within Roman territory, commerce was extensive.

2.11.2 Commodities

Roman agrarian economy included the production and distribution of a variety of commodities. Olive oil was a highly traded staple. It was used for food, heating (also in Roman baths), lighting, and perfumes. An estimated eighteen thousand tons were shipped annually to Rome. Wine was another popular commodity. Based again on a million residents, historians estimate that Rome imported about 100,000 metric tons, which is equivalent to one hundred million liters. The main commodity, however, was wheat since it was the primary staple across the empire. The residents of Rome alone consumed over 200,000 tons annually. Some estimates are as high as 400,000. Rome also imported building supplies, especially marble for its elaborate building projects and lumber for fuel and construction.

Fig. 2.27: Most oil lamps in the Roman period, like this one, were made out of clay.

Fig. 2.28: Olives on a branch.

2.11.3 Micro-Scale Economics

Artisans and Tradesmen

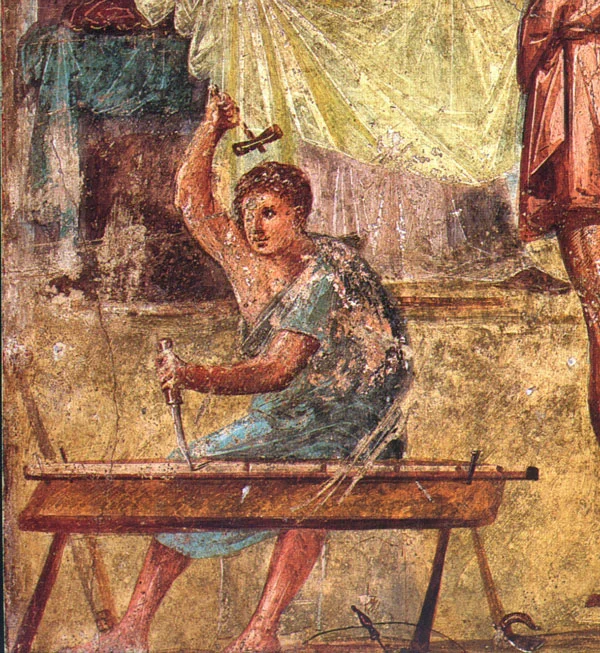

Fig. 2.29: Wall painting of carpenters, Pompeii. 1st century CE.

Throughout the empire, basic staples of life such as food and clothing were met within the family household and through a reciprocal exchange of goods. In villages and larger centers there were numerous artisans who would have bartered or sold their goods and services in shops and marketplaces. These included bakers, grocers, barbers, cobblers, tentmakers, leather workers, carpenters, and blacksmiths.

Fig. 2.30: Wall painting of a woodworker, Pompeii. 1st century CE.

Some Jewish families maintained businesses that produced specialized goods (e.g. pottery, bricks, tiles) or provided specialized services (e.g. woodworkers, masons, smiths). Many of the craftsman and service providers (e.g. wool weavers, barbers, doctors) would have had their shops attached to their homes, contributing to the village economy beyond simply a local central marketplace. As a woodworker (or a worker of hard materials) Jesus and his brothers probably had a shop attached to their house, but during prosperous times under Tiberius they may have also been employed at Sepphoris, about an hour walk from Nazareth. Although money was used more in cities where consumption surpassed production, village economies which were primarily based on bartering still needed to incorporate currency to pay taxes and debts.

One such artisan, named Demetrius, is referred to in Acts 19:24-25: “For a certain silversmith named Demetrius, a maker of silver shrines of Artemis, was providing no little business for the craftsmen. He called them together, along with the workmen in related trades.”

Fig. 2.31: Reproductions of Roman medical instruments. 1st century CE.

Since medicine was not socialized, it was like any other artisan business. Legend has it that the evangelist Luke was a physician who gave up his practice to join Paul in Christian missionary ventures. Medicine in the ancient Mediterranean was well advanced. Surgeons performed amputations, operations on the skull, and tracheotomies. A variety of medical instruments were used, such as stitching needles, lancets, different kinds of forceps, catheters, spatulas for throat examination, and other various tools for examining the internal parts of the body. Dental work was also performed, and sometimes included filling teeth with gold. False teeth were obtained from dead people or animals. People even used ground up teeth, in powder form, for brushing and polishing.

Farming

Fig. 2.32: Traditional terraced vineyard in Israel.

Farming was the most common business activity. Jewish families who leased farms would have contracted to pay rent or a percentage of the crop yield to the landowner. The elite class were often distinguished by their accumulated real estate holdings, as opposed to money or gold (Cicero, On Duties 1.150-51), and would have endorsed an economy based on redistribution where goods generated by working peasants were administered and distributed by institutional structure (like temples, taxation, large lease/landowners). Redistribution established and stabilized great power and wealth among the upper class in urban centres. All too often, however, when the production yield could not sustain the peasant family and forced it into a debt that could not be repaid, the land was taken over by creditors (some of whom were wealthy Sadducees) who exploited the former landowners as tenant farmers. Fear of drought was so prevalent that an entire tractate in the Mishnah, Taanith (“Days of Fasting”) was devoted to religious rituals that would ensure rain.

Fig. 2.33: Olive grove in Israel, much like it would have looked in the first century.

Unlike today, there were no social safety nets such as unemployment benefits or bankruptcy protection. The parables in the Synoptic Gospels, especially Luke, address the pervasive problem of debt and the threats posed by creditors. Recent research has shown that some of the opportunistic landowners in Judea who capitalized on the misfortune of farmers were most likely wealthy Sadducees. In addition to farmers, artisans and various unskilled workers were vulnerable during depressed economic periods.

2.11.4 Transportation

Sea Transport

Fig. 2.34: Floor mosaic of Roman merchant ship found in Lod, Israel. The Shelby White and Leon Levy Lod Archaeological Center. Late 3rd century CE.

Rome’s economic prosperity was dependent on its transportation system. Most of the traded goods were shipped by sea on freighters because they were cheaper, more efficient, and could carry more volume than land transports. Rome contracted enough privately owned freighters to transport 135,000 tons of wheat from Egypt annually. The size of the Roman merchant marine would not be rivaled in Europe until the eighteenth century. The ships, some of which measured 180 feet, were also designed to carry passengers. Travel by sea would have been much more comfortable and safer than land caravans. The major risk to maritime transport was shipwrecks due to inclement weather.

Rome did not limit its trade to the Mediterranean basin. It had direct trade relations with China and India, but usually for more exotic products, like silk and spices. To the south, the Alexandrian merchants had provided markets along the east coast of Africa. During times of relative peace, as in the first two centuries of the Common Era, the Roman economy was truly global. The inland transportation routes were at their peak. In the third century they began to decline and did not rival their efficiency and condition until the advent of the railroad.

Roman Roads

Fig. 2.35: Roman road in Sepphoris. 1st century CE. The wagon wheel ruts are still prominent. Roads varied widely with regard to quality and straightness, but each one increased local range of trade.

The Romans were skillful engineers, well known for building extensive aqueducts to pipe water into cities, arched stone bridges over rivers, and especially paved roads. The famous road system made land travel, communication, and distribution relatively easy and secure with the help of the military, but it was not preferred. Roads were at times cumbersome and slow, animals and carriages had to be maintained on the journey, and the volume that could be transported was much smaller. Land travellers also had to contend with the climate, which could be unforgiving. Carrying enough water for long journeys would have provided an added inconvenience, though in many areas along major routes, towns or hostels were about thirty miles apart, about a day’s trip. Also helpful to travellers were distance markers.

The road system may have been extensive for its day including both public and private roads, but they were not all paved. Those that were paved consisted of hewn polygonal stones (granite or basalt), measuring about a foot and half across and about eight inches in thickness. They were carefully fitted on tightly packed sand or gravel. The best of the roads would have been fairly smooth. Ravines and rivers were crossed with bridges, depressions were filled, and hills were dug in an attempt to keep the roads as straight and as level as possible. The primary roads were eight to ten feet wide. Though they gave the appearance of symmetry, travel on them would have been bumpy since wagons had wooden wheels with an iron track and no suspension.

Fig. 2.36: Terrain of southern Asia Minor (Modern Turkey) that would have been familiar to Paul.

The apostle Paul along with other wandering teachers, merchants, pilgrims, and vacationers, directly benefited from open travel. Broad circulation of goods and services also meant broad circulation of ideas. Without Rome’s economic ambitions and developed transportation system, Paul’s missionary journeys and distribution of letters would have been very difficult. Not only would travel be prohibitive due to the rugged terrain, but would be impossible in the rainy seasons due to floods and washouts. Roman paving stood up to the elements very well. Moreover, caravans and ships would not have stood a chance against opportunistic bandits and pirates were it not for periodic military policing of the roads. Bandits would have certainly been hostile to a Roman citizen.

Alongside exposure to local cultures, travelers like Paul would have encountered symbols of Rome’s supremacy throughout the provinces. Roman coins with an emperor’s head on one side were in broad circulation. Provincial coins also included Roman images to symbolize identity. Cities and temples were adorned with statues of emperors and the gods. Likewise, many buildings were inscribed with honors given to Roman benefactors, emperors, and gods. Roman architecture often overpowered local structures. Art in various forms (e.g. frescoes and reliefs) portrayed the might, wealth, and sophistication of Rome.

Fig. 2.37: Inscription proclaiming Caesar Augustus Son of a God (DIVI-F) and High Priest (PONTIFICI MAXIMO). Ephesus, 1st century CE.

2.11.5 Taxation

Taxation was a continuous and constant source of revenue. It extended to all the provinces and provided a continued source of wealth for Rome. Payment of taxes was not limited to cash, but also included goods. A farmer would have paid his elite overlord with up to forty percent of his crop. The bounty would then be redistributed to nearby areas and sometimes shipped directly to Rome. Withholding tax was regarded as a violation against the supremacy of Rome, and was punished severely. To this day, scholars are not sure how much tax the empire collected and what it was primarily used for. Many have estimated that about half the tax went to the military. The other half of the tax would have been designated to the supply of Rome, wages, and the coffers of the elite. In some provinces, like Syria, much of the tax would have gone directly to paying the military in that region, and in turn would be redistribute back into the local economy. Tax collectors were despised especially in provincial villages and the countryside. So it was not uncommon for collectors to be accompanied by soldiers.

Fig. 2.38: Tribute penny, minted about 36 CE. On the left is the head of Tiberius. On the right is his mother Livia holding an olive branch and a sceptre.

In Palestine, excessive taxation was a major burden for poor rural families. Payment was often difficult and at times resulted in indebted slavery, cruel punishments, and shame. (Plutarch,Luculus 20). The misery resulting from indebtedness even led some to commit suicide (Philo, Special Laws 3.159ff.). Herod’s lavish building programs were certainly a sign of prosperity after several decades of war in the region, but they also led to a fiscal imbalance which brought about considerably arduous taxation and erosion of land, making it difficult for many free small farmers to economically sustain themselves. The decline from free farmers to leaseholders to day laborers and even beggars was not unusual during the Herodian dynasty. During the time of Jesus it is difficult to say whether free small farmers or tenant farmers constituted the majority of the peasant class. Jesus’ parables, analogies, and even temple action would have been thoroughly at home in this agriculturally driven economy that incorporated the tensions between a reciprocal and redistributive systems of exchange.

2.12 Language and Education

Fig. 2.39: Education among the elites was vastly different. This fresco is a depiction of Plato Academy. Villa of T. Siminius Stephanus, Pompeii. 1st century.

Jewish households in first-century Palestine were probably bilingual to some extent, having knowledge of Aramaic along with some Greek. A few may have even known Hebrew. It is, however, very difficult to say which of these languages were dominant. The epigraphic and literary evidence is not conclusive. For example, ossuaries from Judea, which are very personal family items, have been found with inscriptions in Aramaic, Hebrew, and in combination with Greek. One is even trilingual (Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek), which is comparable to the title on Jesus’ cross (which includes Latin). The evidence from the Dead Sea Scrolls is also difficult to assess. While most of the scrolls are in Hebrew, some are written in Aramaic and others in Greek.

Fig. 2.40: Great Isaiah Scroll found in the Cave 1 at Qumran (1QIsa).

It is doubtful that most Jewish peasants would have been literate, beyond perhaps an ability to write their names, numbers, receipts, and contracts for common transactions. Torah may have been taught to young boys in some capacity, though not in established schools as we might perceive. There is little evidence that such education would have included reading and writing. Josephus claims that the law required children to read and learn Torah (Apion. 2.204), but he gives no indication that this practice was carried out throughout the villages of Palestine. Many scholars still appeal to the conclusions of William Harris’ broad study of ancient literacy that approximately ninety percent of the rural population would have been illiterate.

Being illiterate, however, should not be confused with being “unlearned” with respect to family and national history, tradition, and the scriptures. Orality and memory figured very prominently in preserving Jewish identity. Historians argue that the function of memory in oral cultures preserves the past, but it does so with an eye toward the present. Relevance is often the filter through which the past is retold, but the past is not completely lost to the present. While the past is continually (re)shaped and (re)collected so as to have meaning in the present, the present is continually informed and guided by the past, especially if the tradition is older, is adopted by a large number of adherents, and is widespread.

2.13 Entertainment

Fig. 2.41: Wall painting of Mars and Venus in Casa del Meleagro, Pompeii. 1st century CE. Nudity and erotica were widely depicted in Roman society. National Archaeological Museum, Naples.

Entertainment across the empire in the first century took on various forms. Open-air theaters were found in almost every major town, providing the primary venue for performances. The Romans learned from the Greeks how to build theaters with optimal acoustics. Plays, like in modern theaters, were the norm. In addition to plays, people enjoyed hearing music and listening to orators reciting all sorts of literature. Children played with toys, such as dolls, miniature dollhouses with furnishings, balls, tree swings, games similar to hopscotch, and hide-and-seek. Sex permeated the entertainment world of the empire. Sometimes sexual acts were performed on the stage of theaters and were considered ordinary performances. In private venues, among the elite, sexually oriented entertainment was not unusual.

When most people think of entertainment in ancient Rome, they think of gladiators and chariots in grand arenas, like the coliseum in Rome. In such arenas, spectators were witnesses to chariot races, execution of slaves and prisoners of war by wild beasts and gladiators. It was said, that at times the sand became so saturated with the blood of victims that it had to be replaced several times in the day. Wild animals were imported from all over the empire to astonish the crowd. One occasion saw the slaughter of three hundred lions. At the grand-opening of Titus’ amphitheater, 5000 wild animals and 4000 tame ones were slaughtered, including elephants, panthers, rhinoceroses, hippopotamuses, crocodiles, and snakes. One of the most spectacular events was the flooding of the coliseum for the purpose of reenacting naval battles. Thousands supposedly died in these reenactments. Many of these events would have been occasions for gambling.

Fig. 2.42: Coliseum in Rome.

Josephus describes one form of entertainment in Caesarea:

While Titus was at Cesarea, he solemnized the birthday of his brother [Domitian] after a splendid manner, and inflicted a great deal of the punishment intended for the Jews in honor of him; for the number of those that were now slain in fighting with the beasts, and were burnt, and fought with one another, exceeded two thousand five hundred. Yet did all this seem to the Romans, when they were thus destroyed ten thousand several ways, to be a punishment beneath their deserts. After this Caesar came to Berytus, which is a city of Phoenicia, and a Roman colony, and staid there a longer time, and exhibited a still more pompous solemnity about his father's birthday, both in the magnificence of the shows, and in the other vast expenses he was at in his devices thereto belonging; so that a great multitude of the captives were here destroyed after the same manner as before (War 7.3.1 [37-38]).

Try the Quiz

Bibliography

Primary Sources

“1 and 2 Maccabees.” The New Oxford Annotated Apocrypha. Edited by B. M. Metzger and R. E. Murphy. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Josephus. Antiquities of the Jews. 7 vols. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1930–65.

———. The Jewish War. 2 vols. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1927–28.

Whiston, William, ed. and trans. The Works of Flavius Josephus: Complete and Unabridged. Peabody: Hendrickson, 1987.

Polybius. Histories. Loeb Classical Library, 6 vols. Translated by W. R. Paton. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1922-1927.

Tacitus, The Histories. Loeb Classical Library, 2 volumes. Translated by C. H. Moore. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1925.

Barrett, C. K. The New Testament Background: Selected Documents. 2d edn. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1989.

Kee, H. C. The Origins of Christianity. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1973. Especially pages 10–53.

Yadin, Y. Herod’s Fortress and the Zealots’ Last Stand. New York: Random House, 1967. Valuable resource for the archaeological discoveries confirming Josephus’ dramatic account of the Zealots’ last stand at Masada toward the close of the first Jewish revolt.

Secondary Sources

Alston, R. Aspects of Roman History AD 14-117. London: Routledge, 1998.

An introduction to the early Imperial period which corresponds to the New Testament writings. The first half provides a good introduction to the emperors from Tiberius to Trajan. The second half is a well-rounded introduction to Roman society.

Ando, C. Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

A description of the function of Roman political ideology in the unification of Rome and its provinces. This is a more advanced volume written from the perspective of social theorists.

Ben-Sasson, H. H., ed. A History of the Jewish People. Harvard University Press, 1976.