Module One

Introduction to the Section

The initial step in a historical understanding of the New Testament is an awareness of the complex setting in which it was written. This is often referred to as the “background” or “context” of the New Testament. It allows us to be transported back into a world that is completely different from our own. For the writers of the New Testament, this world was their home, and was therefore assumed in their writings. Since they were writing to contemporary audiences about contemporary issues, using the language, ideas, and symbols that were public knowledge, there was no need to explain the background. For example, there was no necessity to explain to their readers the Roman political system, social customs, family life, economic structures, village life, legal system, religious beliefs and so on. There was even no need to explain what was meant by weighty terms and titles that we encounter in the New Testament, like Son of God, kingdom of God, the Word, and Christ. These were simply an assumed part of the first-century Mediterranean world. In this first section of the book, we attempt to open up that background by focusing on three major segments of it: the political, the social, and the religious.

Political Context

1.1 Introduction

Every culture is influenced by the memories of its history, whether they are recent memories or those passed down from generation to generation. The past is a shaper and teacher of the present. We are who we are, in many ways, because of what preceded us. The same applies to the New Testament writers. It is impossible to understand their context without some knowledge of the major events that shaped their world and culture. In this chapter we will explore the major political events that shaped and defined the eastern part of the Mediterranean world, especially the lives of the Jewish people in Palestine.

Fig. 1.1: Wilderness near the Dead Sea.Fig. 1.1: Wilderness near the Dead Sea.

Our first impression when we begin to read the New Testament is that it is a continuation of the Old Testament. If we begin with Matthew’s Gospel, the first major character that we encounter is John the Baptist. He seems very familiar. He is a prophet, calling for repentance. His clothing resembles that of Elijah. His message echoes Isaiah and Malachi. He is located in the wilderness. But the resemblance is only superficial. The eastern Mediterranean of the first century is a very different place. Its architecture includes cites, buildings, and monuments that glorify Rome and its emperors. Its language is largely Greek, and its culture has undergone Greco-Roman influence. In Jerusalem, we find one of the grandest temples the world had known to that time.

How did this cradle of Christianity, called “Judaea” and later “Palestine,” undergo such dramatic change? (The term “Palestine” is used for this region of the Middle East, and is not meant to be synonymous with any political entity. Some prefer to call the region “Greater Palestine” to indicate the difference.) How did the province of Judea come to be governed by a Roman Governor? How did Rome come to rule? How did the Herodian dynasty emerge? In answering these and other related questions, we encounter a dramatic and intriguing story of victory, defeat, suffering, strife, and endurance.

1.2 The Pre-Exilic and Exilic Periods

Fig. 1.2: Assyrian relief

Under the reign of King David, all twelve tribes of Israel were united. This period was remembered centuries later, even by first-century Christians, as the “golden age” of the Jews. However, the unified kingdom did not last. It eventually became marred by schism, dividing the ten tribes in the north, which became the kingdom of Israel, and the two tribes of the south, which became the kingdom of Judah.

Political division often leads to vulnerability. In the eighth century BCE, the Assyrians conquered the northern kingdom of Israel, destroyed its capital city Samaria, and enslaved most of its inhabitants (722-721 BCE). The kingdom of Israel was exiled to Assyria. Those that remained were intermarried with Assyrian colonizers, which contributed to a peaceful conquest. When the Israelites eventually returned back to their homeland, they distanced themselves from those who had remained and intermarried.

About a century later, the Babylonians rose to power, conquered the Assyrians, and seized control of the eastern Mediterranean region. In the process, under the leadership of King Nebuchadnezzar, they invaded the southern kingdom of Judah and destroyed Jerusalem along with its grand temple (587-586 BCE). Many of the residents were rounded up and forcibly brought to Babylon where they were exiled for the next half-century.

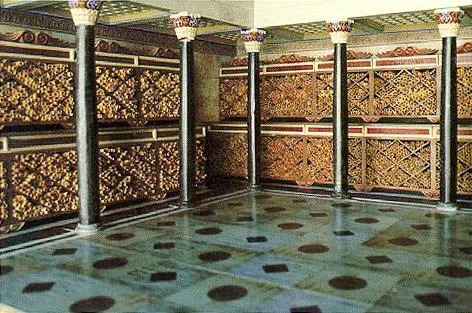

Fig. 1.3: Ishtar Gate, dedicated to the Babylonian goddess Ishtar. This was one of several gates leading to inner city of Babylon. It was built during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II in 575 BCE. Pergamon Museum, Berlin.

1.2.1 Exile

The term “exile” conjures up social, political and religious images of judgment, captivity, banishment, displacement, uprootedness, alienation and deportation. In the Old Testament, exile constitutes a major theme, weaving itself through almost every major account from Genesis to Malachi. It is so pervasive that the Old Testament has sometimes been called a metanarrative of exile. Some of the more well known expressions of exile are found in stories such as Adam and Eve’s banishment from the Garden of Eden, Abraham’s journey to the land of Canaan, Joseph’s deportation to Egypt, the Israelite captivity in Egypt, Moses’ wandering in the wilderness, David’s escape from Saul’s paranoia, and Israel’s exile in Assyria and Babylon. The theme of exile, however, does not function in isolation. In the two most important expressions for the study of the New Testament—the stories of Adam and Eve’s banishment and the deportation of the Israelites to Babylon—exile, which is always a result of sin, is accompanied by the hope that God will liberate and restore.

Fig. 1.4: Masaccio, Expulsion of Adam and Eve. 1426. Brancacci Chapel, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence.

While the biblical accounts of exile in and of themselves serve as an important background for New Testament studies, it is the retelling and re-experiencing of these accounts among the Jewish people in the Second Temple period that is all the more influential. When the literature of this period is probed for a fulfillment of the promises proclaimed by the exilic prophets, one is hard pressed to show a “post-exilic” return in the grandiose manner often predicted. The hope of the prophets, from Isaiah to Zechariah, of a return from exile was not realized.

During the Second Temple period, some in Palestine still considered themselves as being in exile because they were under foreign rule—which meant that Yahweh had not yet returned to Zion (Ezra 9:8-9; Neh 9:36). This perception was continually confirmed by the oppressive regimes of the Seleucids and the Romans. The underlying reason why some Jews saw themselves as still remaining in exile was their assumed perennial state of sinfulness (Bar 1:15-3:8;1 En. 89:73-75), a concept which is grounded in the “cursing and blessing” motif in Deuteronomy 27-32. For these Jews, the true return from exile was inseparably bound with the forgiveness of sins. As long as foreign oppressors dominated Israel, the sins were not yet forgiven.

On the whole, the exilic motif is found dispersed in literature extending from the Babylonian era to the Rabbinic period (Sir 36:8; T. Mos. 10:1-10; 1 Enoch 85-90; T. Levi 16-18; Apoc. Abr. 15-29; T. Jud. 24:1-3; Jub. 1:15-18, 24; T. Naph. 4:2-5; T. Ash. 7; T. Benj. 9; 2 Macc 1:27-29; 1 Esdr 8:73-74; 2 Esdr 9:7).

1.2.2 Cyrus the Great

One constant about empires is that they rise and fall. When the Persians grew in military might under the leadership of Cyrus the Great, they advanced eastward toward the Mediterranean and defeated the Babylonians in the 6th century BCE. The Persians allowed the exiled peoples in Babylon to return back to their homelands. Some of the Jewish people returned, but the majority either remained in Babylon or assimilated themselves in regions outside of Palestine. These came to be called “Diaspora” Jews. The story of those who returned is told in Ezra and Nehemiah, with additional references in Ezekiel, Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi.

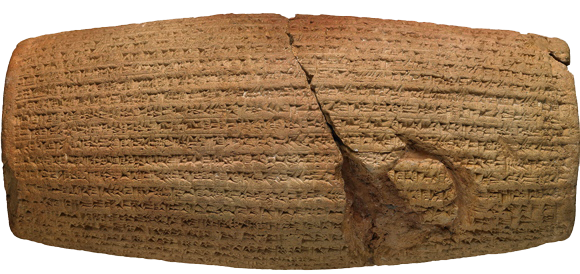

Fig. 1.5: Cyrus Cylinder inscribed with Babylonian cuneiform, recording the account of Persia’s defeat of the Babylonians in 539 BCE. British Museum, London. c. 539-530 BCE.

Since the exile was explained as divine judgment for Israel’s covenant failings (see Mal 2:11), the Jewish leadership returned to Jerusalem with a profound desire to right the wrongs of the past. Religious zeal at the national level characterized the return. Although many sacred artifacts, like the Ark of the Covenant, were forever lost, some of the old temple objects were brought back to Jerusalem. With a handful of reminders of the temple and fervent zeal, the new leadership of Ezra and Nehemiah inspired the rebuilding of a new temple. The five-year building project was eventually completed in 515 BCE – but little did they know that it would only last six centuries. This period of history, from the rebuilding of the temple to its destruction in 70 CE by the Romans, is often referred to as the “Second Temple Period”. This was a religiously and culturally vibrant time that would prove influential many years later in the development of Christianity.

The Greek writer Xenophon (428-354 BCE) is often cited as a source for our understanding of Cyrus. However, his work, the Cyropaedia (“Education of Cyrus”), should be regarded as a pseudo-historical account of Cyrus’ life and may not be accurate. Nevertheless, here is an excerpt worth pondering:

He ruled over these nations, even though they did not speak the same language as he, nor one nation the same as another; for all that, he was able to cover so vast a region with the fear which he inspired, that he struck all men with terror and no one tried to withstand him; and he was able to awaken in all so lively a desire to please him, that they always wished to be guided by his will. Moreover, the tribes that he brought into subjection to himself were so many that it is a difficult matter even to travel to them all, in whatever direction one begin one's journey from the palace, whether toward the east or the west, toward the north or the south (Cyropaedia 1.1.5).

1.3 The Hellenistic Period

The term “Hellenistic” simply means “Greek.” The word comes from Hellas, which was the Greek word for Greece. In the ancient world, Hellas was associated with political, religious, and social reform—at times forced. Subdued peoples were expected to govern themselves according to Greek polity and philosophy. They were also expected to speak the language. Because of Alexander, Greek became the common language for trade and diplomacy around the eastern Mediterranean basin. Everyone from the poorest of the poor to the richest of the rich learned Greek. Eventually, the use of Greek spread throughout the Mediterranean.

1.3.1 Alexander the Great

Fig. 1.6 A bust of Alexander the Great

One of the most celebrated figures in the history of Western civilization is Alexander of Macedon, most commonly known as Alexander the Great. His “greatness” has not been attributed to him for his extraordinary military battles and conquests only, but also for his export of Hellenistic culture. Hellenism had been slowly migrating through trade and colonization, but Alexander’s conquests accelerated the expansion considerably. Alexander was well educated, having studied under Aristotle, and he was ambitious. King Philip, Alexander’s father, was a charismatic leader who asserted Macedonian hegemony by defeating the southern cities of Greece. Alexander’s own dream, when he ascended to the throne of Macedon, was the Persian territories to the east, such as Anatolia (Asia Minor). He would go on to surpass his dream.

Alexander’s campaign began in the 4th century BCE, when he led his forces from Macedonia eastward. His first major battle (of three) against the Persians took place at the Granicus River in 334 BCE. This important victory led to the collapse of Asia Minor. Soon after, he moved south, freeing Greek cities that were along the Aegean Sea.

As the small, but mobile Macedonian force of 30,000 strong moved east, the Persian king, Darius III, knew he had to confront Alexander immediately. Darius raised an army of 100,000 and met Alexander’s forces at the Plains of Issus in 333 BCE. The Persian army’s superior size proved to be a liability. It was too large for the battlefield, which was constricted by mountains on one side and the Mediterranean on the other, allowing Darius’ lines to be quickly breached by Alexander’s swift, armored cavalry. Darius fled and the battle belonged to the Macedonians.

Fig. 1.7: Floor mosaic of the battle of Issus, between Alexander (on far left) and Darius III (central figure on right) found in the House of the Faun, Pompeii. 1st century CE. National Archaeological Museum, Naples.

Alexander continued to advance southward. On his way to Egypt, he conquered the region of Judaea. In Egypt, he renamed its major city after himself: “Alexandria”. When Egypt was subdued in 332 BCE, he continued his advance to the Euphrates and followed its course until he entered Mesopotamia. North of Babylon, Darius held a massive army of 200,000 in a vast open area called the Plain of Gaugamela. Once again, Darius assumed that the vast size of his army would overwhelm and obliterate the smaller Macedonian force. Once again, Darius miscalculated. Alexander attacked the center of the Persian forces, which was an unconventional tactic, but nonetheless the right one for that day. Darius fled and two years later was found dead.

Alexander plundered the Persian treasuries, freeing its cities (such as Babylon). He soon also conquered the great Persian capital of Persepolis, which he later burned to the ground. He continued to move east toward India, where he defeated the Indian king Porus. Up to this point, his forces had crossed over 11,000 miles in eight years of constant campaigns, which was unprecedented in the history of warfare. In western India, his commanders compelled Alexander to turn the army around – they had had enough. After two years, they made their way back to Babylon, which Alexander wanted to make as his capital. He died of a severe fever on his way back to Babylon in 323 BCE. He was a month shy of his 33rd birthday.

The influence of Alexander was enormous. In the wake of the campaigns, the Greeks founded and built many cities and modeled them after their own Grecian style. Twenty of these cities bore his name, but none compared with Alexandria in Egypt, which became a leading city in the ancient world. The region of Palestine was not immune from the building program. One of these Grecian cities was Sepphoris, only a short distance from Jesus’ hometown of Nazareth. The forging of a huge empire led to a universal monetary currency and common language, which accelerated trade and the exchange of ideas. Greek culture would dominate the eastern Mediterranean for the next nine hundred years until the coming of Islam in the seventh century. The mark that Alexander’s conquests left upon the world is profound.

Map 1.1: Alexander’s empire at the time of his death.

1.3.2 The Ptolemies and Seleucids

Fig. 1.8: A bust of General Ptolemy I, 3rd century BCE. Louvre Museum, Paris.

Though Alexander conquered vast regions, built magnificent cities, and profoundly influenced the expansion of Greek culture (Hellenism), he did not appear to have a plan of succession. After his death, four prominent generals divided the empire among themselves. Two of these generals, Ptolemy I Soter and Seleucus I Nicator, forged kingdoms that became very influential in the political and religious identity of the Jewish people in Palestine. By the beginning of the first century CE, many of the political and religious ideas, groups, and institutions that emerged under Alexander’s successors had already been woven into the social fabric of Judaism. For example, it was during this post-Alexander period when we see the rise of groups like the Pharisees and Sadducees. We also see a significant development of religious ideas like heaven, hell, angels, and resurrection.

General Ptolemy governed the regions that were southwest of Palestine, primarily Egypt, with Alexandria serving as the capital. He established the Ptolemaic Empire or Dynasty, which would endure under a succession of rulers (called the Ptolemies) until the reign of Cleopatra in the latter half of the first century BCE when the Romans finally seized control of Egypt.

General Seleucus carved out the region to the north and northeast of Palestine, which came to be known as the Seleucid (or Syrian) Empire or Dynasty, with its capital situated in Antioch of Syria. The succession of rulers, who often took on the name Seleucus or Antiochus (in honour of the capital, Antioch), eventually came to an end in 64 BCE, when the Roman General Pompey defeated Antiochus XIII.

Wedged in between these two great empires was the land of Palestine, which was prized for its coastline, agriculture, and trade route that connected Asia Minor and Egypt. The two empires, which had a disdain for each other, also vied for control of Palestine. This animosity led to countless battles, leaving the residents of Palestine as the unfortunate victims of war.

The Ptolemaic Empire at its height in 270 BCE.

1.3.3 The Ptolemies

After several battles, Palestine fell under the control of the Ptolemies. Although there were sporadic battles with the Seleucids, the Ptolemies ruled Palestine for over 120 years (320-198 BCE). For the most part, life in Palestine under Ptolemaic rule was peaceful. The Jews were permitted to freely practice their faith in public. The peace was also maintained politically through the establishment of a temple-state around Jerusalem. This region was governed by priests, who were responsible for collecting taxes on behalf of the local Ptolemaic governor.

During this period, many Jews resided outside of Palestine. A considerable number migrated to cities like Alexandria where they established permanent Jewish communities. Eventually, Jews were integrated into the culture and took on many of its attributes, such as fashion and the common use of the Greek language. As a result of the integration over one or two generations, the Hebrew Scriptures were no longer used in synagogues outside Jerusalem. The Hebrew language fell into disuse in favour of Greek. According to the ancient Letter of Aristeas, written probably in the second century BCE, the chief librarian of Alexandria urged the King of Egypt, Ptolemy II Philadelphus (who ruled 281-246 BCE) to have the Hebrew Torah translated into Greek. The librarian argued that such a translation would enhance the collection of the library. When the King agreed, the high priest in Jerusalem chose seventy-two men, six from each of the twelve tribes, who were fluent in both Hebrew and Greek.

Fig. 1.9: Reconstruction of the Alexandrian Library, which was one of the most significant libraries from the 3rd century BCE to the time of its destruction in the Roman period.

According to Aristeas, when the translators arrived in Alexandria in about 250 BCE, the King posed numerous questions to them. Being astounded at their wise responses, he commissioned them to translate. The seventy-two translators emerged in seventy-two days. The new translation was so revered that the Jews of Alexandria placed a curse on anyone who attempted to alter it. For Greek-speaking Jews and Christians in the first century, this translation was a standard text, and would continue to be so in the Christian church for centuries to come. In the Eastern Orthodox tradition, it continues to be the authoritative version of the Old Testament. Today, scholars refer to it as the Septuagint, which means 70 (abbreviated as LXX), reflecting (in rounded terms) the number of translators and the number of days it took to complete the translation.

1.3.4 The Seleucids

After a century of conflicts with the Ptolemies, the Seleucids, under the rule Antiochus III, finally gained control of Palestine in 198 BCE. For the average Jew, the tranquility of daily life and the freedom of religious expression and worship would soon turn to disaster and despair.

Fig. 1.10: Replica of 3rd century BCE bust of Antiochus lll, Musée du Louvre, Paris.

When Antiochus III seized control, the Jewish leadership was split into two factions: (1) the house of Onias, which controlled the office of the high priest and endorsed the policies of the former overlords, and (2) the house of Tobias which endorsed the Seluecids. When Antiochus IV Epiphanes succeeded his father (175-163 BCE), he replaced the pro-Ptolemaic High Priest Onias III with Onias’ brother Jason, who supported the Seleucids. For the Jews of that day, the high priest occupied the most important political and religious office. Under Jason, Jerusalem began to be transformed into a Greek city.

The reaction among the Jews was mixed. Those who embraced it, tended to be among the upper class. They welcomed the sophisticated Hellenistic ideas, social practices, entertainment, and building programs. They tended to immerse themselves into the culture, attending Greek theaters, wearing Greek fashion, and changing their Semitic (Jewish) names into Greek names (as was the case with the High Priest – Jason).

Fig. 1.11: A plate featuring a nude athlete in Greek style.

One of the most controversial building projects was the construction of a gymnasium and an attached racetrack. Since athletes often competed in the nude, some of the Jewish participants even went through a surgical procedure to reverse their circumcision so they could look like their Greek counterparts. Moreover, celebrated athletic events were often inaugurated by paying homage to the Greek pantheon.

Many Jews resisted the Hellenistic transformation of both their city and the broader culture. A more radical group of Jewish opponents, emerging out of the peasant class, were the Hasidim (or Hasideans), meaning “the pious ones.” This group consisted of devout Jews who were passionate adherents to the Law of Moses. They feared that on almost every level of society, their Jewish identity was being eroded and threatened. They vehemently opposed the building of the gymnasium and racetrack, because they regarded public nudity, the reversal of circumcision, and the invocation of the Greek gods to be a gross violation of the Abrahamic covenant between God and his people. In a matter of decades, the Hasidim would branch off into two major political groups: the Pharisees and the Essenes.

Fig. 1.12: Bust of Antiochus IV 'Epiphanes'

Under Antiochus IV, the policy was to assimilate Jews into Greek culture and once and for all put an end to the Jewish religion. Though Antiochus was nicknamed Epiphanes (which means “the manifest one” implying a manifestation of God), the Jews, being fond of wordplay, nicknamed him Epimanes (which means “the insane one”). The nickname was well deserved.

In the planning stages of a major invasion of Egypt, Antiochus’s officials realized that the cost would exceed their resources. One of the solutions, suggested by a Hellenistic Jew named Menelaus, was to raise taxes for all residents in Palestine. Menelaus volunteered to organize the drive for a price: that he be made High Priest in Jerusalem. Antiochus consented and deposed his previous appointee, Jason. This deposition of Jason, in effect, broke the priestly line of succession that supposedly began with Aaron, the brother of Moses. Again, for pious Jews, this was a gross violation of their sacred tradition, escalating not only the anger toward the Seleucids, but also the strife between the temple establishment and the common people.

Despite some initial successes, Antiochus’ invasion of Egypt failed. He did not appropriately account for the growing political influence of Rome. By this time Rome had become the dominant power in the Mediterranean and had exerted dominion over Asia Minor. Since Rome was very protective of the vast grain supply in Egypt, it placed considerable pressure on Antiochus to abandon his plans.

Fig. 1.13: Tetradrachm depicting Antiochus IV on the left and Zeus on the right, with the caption “King Antiochus, manifest ion of God.”

Back in Palestine, a rumor reached the ears of the former High Priest Jason that Antiochus had died in Egypt. Seeing a chance to retake his position in Jerusalem, he and his supporters deposed Menelaus. Antiochus, however, was not dead. When he returned back to Palestine, with a wounded ego, he interpreted the deposition of Menelaus as an act of rebellion. In response, Antiochus sent an army to hunt down and kill all who were involved in the “rebellion” and reinstated Menelaus as the High Priest. Antiochus’ anger toward the Jews escalated. His forces ransacked the temple and slaughtered some of the inhabitants of Jerusalem. This was only the beginning of the devastation that was to befall devout Jews.

By 168 BCE, Antiochus had sacked the city of Jerusalem, torn down its walls, and looted the temple treasury. He instituted decrees prohibiting temple festivals, circumcision, and possession of the scriptures. Violations of these prohibitions were punishable by death. The worship of Greek gods became mandatory and soon festivals for the god Dionysius were commonplace in Jerusalem’s streets. In the winter of 167 BCE the temple became a pagan site where the worship of Zeus was practiced. For the next three years, pigs, which were considered unclean animals by Jews, were sacrificed by the Seleucids on Israel’s holiest altar. For devout Jews, this was the ultimate desecration (1 Macc. 1:41–63).

1.4 The Hasmonean Period

In 167 BCE, the previously unknown village of Modin, located about 35km northwest of Jerusalem, became the site that would forever be associated with one of the most astounding revolts in Jewish history. It began with a routine visit by a royal official of Antiochus IV, who demanded the leading priest of the village to offer a sacrifice to Zeus on the Jewish altar. This was a routine method of subjugation and was a show of the supremacy of Antiochus.

Fig. 1.14: Coin from the Hasmonean Period depicting an anchor

The results in this village, however, were far from routine. When the crowd was gathered around the village altar, Mattathias, the senior priest, was commanded to sacrifice a sow. He refused because he could not break the Mosaic Law. When another Jew was chosen and willingly came forward to slay the animal, Mattathias was enraged. He drew his sword and killed his fellow Jew. He also killed Antiochus’ official, and demolished the altar. Then he fled to the mountains along with his sons and a number of followers. This revolutionary act would lead to the famous Maccabean Revolt, so named after Mattathias’ son and successor, Judas who was nicknamed “Maccabeus”, which means “the hammerer”. It is also known as the Hasmonean Revolt, named after the family Hasmon to which Mattathias, Judas, and the other sons belonged.

Judas led a highly effective guerrilla war against the Seleucids, usually inflicting heavy damage on the forces in the mountain passes where the usually effective phalanx formation of the Greeks could not be utilized. By 165 BCE, the Maccabean revolutionaries cleared their way to the temple mount. They reclaimed their sacred site, dismantled the pagan artifacts and altar, and rededicated the temple for the Jews. The celebration of the temple’s rededication is known as Hanukkah (“Festival of Lights” in Josephus Ant. 12.7.7 and “Feast of Dedication” in John 10:22) and has been annually celebrated by Jews on the 25th day of Kislev (mid December).

Fig. 1.15: At Hanukkah, the Menorah (branched candelabra) has been annually lit for over two thousand years. This is a Roman mosaic from Tunis, 3rd-5th century CE. Brooklyn Museum.

After Judas was killed in battle in 160 BCE, his brothers Jonathan and then Simon succeeded him. When Jonathan became High Priest, he had the walls of Jerusalem rebuilt along with many of the other buildings that were leveled during the war.

The military strategy implemented by Mattathias and Judas culminated in victory over the Seleucids. But it was not the only factor. During the campaign against the Maccabees, Antiochus was also battling the Parthians to the east. Antiochus’ sudden death in 164 BCE, the fractured pressure on the army, and internal civil conflicts eventually led to the increasing instability of Seleucid control. By 142 BCE, the Maccabean revolutionaries established political independence.

Simon was credited with winning independence from the Seleucids. He renewed the treaty with Rome, originally made by his brother Judas. As the proclaimed High Priest and commander of the Jews, Simon officially began to consolidate religious, military, and political authority within the institution of a Jewish state. The popular assemblies in Jerusalem declared Simon the “High Priest forever until a trustworthy prophet should arise” (1 Macc 14:41).

The excitement of victory against the Seleucids and the exhilaration of achieving political independence did not last. Peace was short lived, but this time the instability and conflict developed from within. Internal strife, caused by greed and ambition, would come to characterize the new nation. The Hasmonean political agendas alienated many of their former supporters. Among those supporters were the pious Hasidim, who would later split into the Essenes and the Pharisees.

The Hasidim were at odds, religiously and politically, with the aristocratic and politically minded supporters of the Hasmonean priest-kings. It is believed that the Sadducees emerged out of this aristocracy. The Hasidim primarily held influence throughout the rural regions of Palestine, and were constant critics of the Hasmonean autocracy. Tensions were especially high during the reign of the Hasmonean king Alexander Jannaeus (103-76 BCE), who is said to have violently suppressed numerous rebellions—at one time crucifying approximately 800 Hasidim. Finally, in 63 BCE, political independence gave way to Roman control. In the end, Jewish political independence, which would not again be established until 1948, lasted for only 80 years.

1.5 The Roman Period

Fig. 1.16: Arch of Titus, Rome. 82 CE. The relief depicts the Roman soldiers carrying a Menorah from Jerusalem as a symbol of victory over the Jews.

While the cradle of earliest Christianity was Palestinian Judaism, its development and expansion can be credited to the Roman Empire of the first century. Rome’s infrastructure, political and social policies, and military created the ideal conditions for early Christian missions. As Christianity expanded throughout the empire, its formation was influenced by the richness and diversity of Roman culture and its inherited Hellenistic traditions. The broad use of Greek in the eastern part of the empire, and the use of Latin in the west, were the means through which the faith was understood and communicated. The philosophical traditions, the rhetorical methods, literary genres and artistry, the political, legal, ethical structures, and social relations (such as slave/masters, husbands/wives/children, classes) among other aspects, all influenced how Christianity took shape.

Roman Control of Palestine

Roman expansion into the eastern regions of the Mediterranean, such as Palestine and Asia Minor, began to take shape in the first half of the second century BCE. Taking advantage of the longstanding strife between the Ptolemaic and Seleucid dynasties, and the threat of the Parthians, the Romans made their way into the region and gained control of Egypt and much of Asia Minor. When the Seleucids (under the rule of Antiochus IV) were weakened and fractured by both the Parthian and Maccabean campaigns, Rome’s influence and power became more prominent. Political instability creates military weakness and inroads for aggressive rivals. The Eastern Mediterranean did not fall under Roman supremacy for another eighty years.

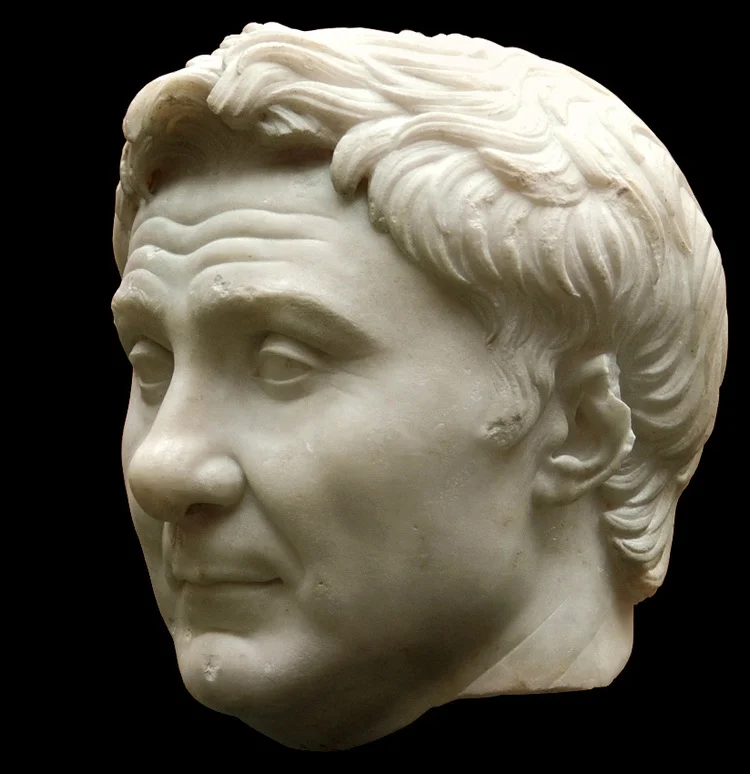

Fig. 1.17: General Pompey. Marble bust, c. first century CE. New Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen.

Before Pompey seized control of Palestine in 63 BCE and put an end to Jewish independence, he was sent by Rome to hunt down pirates in the Mediterranean. In the process, he seized and controlled various strategic parts of the shoreline. During this time, he was informed that the Jews were in civil distress, fighting internally for political supremacy. The civil conflict raged between two brothers, Hyrcanus II and Aristobulus II, who were sons of the deceased Queen Salome Alexandra (76-67 BCE).

The younger son, Aristobulus II, was High Priest and King of Judea, and a supporter of the Sadducees. Hyrcanus shared his mother’s political and religious views, and supported the policies of the Pharisees. The weak willed Hyrcanus was also influenced by the ambitions of Antipater of Idumea, who became the founder of the Herodian Dynasty and was the father of the future King Herod.

Fig. 1.18: Replica of a Roman centurion’s helmet.

Pompey was asked to intervene in the conflict. He seized on the opportunity and led his forces to Palestine, meeting no resistance in the process. He liberated Damascus and the many Greek cities known as the Decapolis, all of which were under Hasmonean governance. Pompey eventually made his way to Jerusalem. After several attempts at intervention, Pompey seized political control himself. His only resistance came from the forces of Aristobulus II, which Pompey crushed in Jerusalem. Hyrcanus II and his Idumean cohort Antipater made no attempt to oppose Pompey. The battle claimed 12,000 Jewish lives. Pompey also imposed a heavy tribute on the city, and executed leaders who opposed him. He instituted Hyrcanus II as the High Priest, and together with Antipater, they became Rome’s client rulers. The Romans (later Byzantine empire) would remain in control of that region for approximately the next 600 years.

Although the Roman conquest of Palestine was successful, the Roman Republic was in turmoil. Civil war ensued and was eventually decided at the famous battle of Actium on the west coast of Greece between the forces of Antony (and Cleopatra VII) and Octavian (born Gaius Octavius Thurinus; sworn as Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus). By 27 BCE, the Republic was replaced by the empire with Augustus at the helm. Although the term “empire” was derived from the Latin imperium, meaning “power”, it developed into territorial, namely provincial, oversight by Roman governors. This new era was marked by political peace, economic prosperity, and cultural expansion.

Fig. 1.19: Statue of Emperor Augustus of Prima Porta, Vatican Museum, c. 15 CE

Pax Romana is a latin designation for “the peace of Rome.” Although many of the Roman citizens praised Augustus as the bringer of peace; the sentiment was not universal. Many conquered peoples saw it differently. Nevertheless, the success of Roman expansion and unification can be credited to the Pax Romana, which was achieved by a combination of a strong military and political policies that focused on the unification of the provinces through cultural acceptance, incorporation, promise of security, reciprocity and rewards. The Romans hailed Augustus as the savior of the world, the bringer of peace, and one who brings the “good news” (gospel).

These lofty designations attributed to Augustus throughout the empire, particularly on monuments and coins, were appropriated by the early Christians and applied to Jesus. In the Gospel of Luke, for example, Jesus is called “savior” and “bringer of peace.” It is important to keep in mind that these were political titles that had political ramifications. The early Christians wanted to convey that it was not the Roman emperor who brings peace and salvation; it is Jesus Messiah, the true Lord and Son of God. Many scholars have come to see the Christian designations as politically subversive.

By the beginning of the first century, the empire spanned from Britain to Syria, and from central Europe to North Africa, completely encompassing the Mediterranean Sea and much of the Black Sea. Never before or since has the Mediterranean world been so politically unified.

Map 1.3: Roman Empire in the first century.

Major Roman Emperors in the First Century

Augustus (27 BCE to 14 CE)

Tiberius (14-37 CE)

Caligula (37-41 CE)

Claudius (41-54 CE)

Nero (54-68 CE)

Vespasian (69-79 CE)

Titus (79-81 CE)

Domitian (81-96 CE)

1.6 The Herodian Dynasty

Fig. 1.20: Parthian prisoner of a Roman soldier, Arch of Septimius Severus. Rome.

Antipater of Idumea founded the Herodian Dynasty. He had two sons: Herod and Phasael. After Antipater’s death in 43 BCE, his son Herod won Rome’s favour as a successor. When the Parthians invaded Syria and Palestine in 40 BCE, they captured the High Priest Hyrcanus II and killed Phasael. Herod fled to Rome. He made a deal with the Senate that if he defeated the Parthians on their behalf, he would be made king of the Jews. The Senate equipped Herod with a Roman force and, after his successful campaign, he was inaugurated king of the Jews. Due to his Idumean ancestry (biblically a descendent of Esau, an Edomite) many devout Jews resented his rule over them. He tried to appease the Jews by marrying a woman of Hasmonean descent.

1.6.1 Herod the Great

Herod the Great followed in the Hellenistic tradition of kings, having the monarchic authority of Alexander the Great and the Hasmoneans. This meant that he was not only a warlord, but also the supreme judge and legal authority. As king, he commanded the army and had control over the socio-economic affairs, but his authority was not extended to religious matters. Only High Priests had ultimate control of Jewish religious life.

Fig. 1.21: Prutah, used during the time of Herod.

Herod did not have the reputation of being a benevolent ruler. His atrocities were so well known that they even reached the ears of Augustus, who supposedly remarked that it was better to be Herod’s pig (hus) than his son (huios)—a wordplay in Greek. Even if this anecdote did not originate with Augustus, it accurately represented a common sentiment. For example, Herod ordered the execution of one of his wives and at least three of his sons, because he suspected they sought his throne. His paranoia also led to the execution of forty-five subjects who were accused of plotting a coup. According to the Gospel of Matthew (1:16-18), Herod had ordered the killing of all male children in Bethlehem after learning that a rival king of the Jews was born there. Although there is no other record of this infanticide, it does not seem impossible when one considers Herod’s reputation.

Fig. 1.22: Ruins of Caesarea Maritima, Israel.

Despite his paranoia and ruthless practices, Herod was an efficient ruler and a master builder. His most important legacy was his building projects in urban centres. Two of his grandest projects were the city of Caesarea Maritima and the Temple of Jerusalem. When Herod began the reconstruction of Caesarea Maritima (named in honour of Caesar Augustus) in about 22 BCE, it was largely a pagan city. The project was extensive, employing thousands of workers. In addition to the famous harbour that rivalled the one in Athens, the construction included temples, public buildings in grand Roman-style, warehouses, baths, wide roads, and markets. When the harbour was complete, in about 13 BCE, Caesarea became the capital of the province of Judea and the official residence of its prefects (including Pontius Pilate).

Next to Jerusalem, which had a population of about 200,000, Caesarea was the largest city in Judea, with population of approximately 125,000. In Acts 10, it is the location of Peter’s baptizing of the Centurion Cornelius, his household, and his soldiers. It was also the place of Paul’s lengthy imprisonment (Acts 25). Later, after the Jewish war with Rome (66-70 CE), about 2500 captured revolutionary fighters were executed in Caesarea’s gladiator forum.

Herod’s expansion of the temple in Jerusalem around 19 BCE was a massive undertaking (Ant. 15.380-390; War 1.401). The old temple, originally constructed under the leadership of Zerubbabel almost 500 years earlier and renovated under the Hasmoneans, served as the platform. It was situated on top of the Temple Mount, which was also known as Mount Moriah. The project employed 10,000 skilled labourers and another 1000 priests as masons and carpenters in order to conform to ritual requirements (Ant. 15.389-390). When the temple was finally completed in 63 CE, it measured 280 meters (south wall) by 485 meters (west wall) by 315 meters (north wall) by 460 meters (east wall), for a total area of 144,000 square meters , which was double the previous size and would have been enormous compared to other temples in the empire.

Fig. 1.23 Replica of Herod’s Temple, Jerusalem.

Although Herod boasted that the temple was his gift for the Jews and for the glory of God, there was no mistaking that the temple contributed to the glory of Rome (Ant. 15.382-387). A golden eagle was hung over the Eastern (“Great”) Gate. Some scholars believe that this was to show Rome’s supremacy, but more recent scholarship has argued that, since this was a period of strict opposition to “Graven images,” the statue need not have been Roman to cause controversy. It would have been appropriate, in the eyes of some, to symbolize God’s power with an eagle (as in, for example, iconography pertaining to John’s Gospel) whereas others would have been offended by it. In either case, Josephus reports that, just prior to Herod’s death, a few youths pulled it down (Ant. 17.6.1-3; 151-63; War 1.33.2-4; 649-55). If this was an attempt to symbolize Roman supremacy in the temple, it would not be the last. In 40 CE, the emperor Caligula attempted to install a statue of himself in the temple (Ant. 18.257-62). A few scholars have associated this with the “abomination of desolation” in Jesus’ Olivet Discourse (Mark 13:14).

Herod died in 4 BCE. The cause of his death is not known, but it had something to do with illness. Common suggestions include dropsy, Fournier’s gangrene, kidney disease, or intestinal cancer. In keeping with his megalomania, he ordered the execution of leading Jewish figures on the day of his own death. Suspecting that the Jews would not mourn for his death, he was assured by this action that there would be mourning among the Jews at the time of his death—even if it were not for him. Though the soldiers reportedly herded the people into the arena for this purpose, the orders were overruled after his death and the slaughter did not occur.

1.6.2 Herod’s Three Sons

After Herod’s death, the political and economic landscape became more precarious. Since Palestine was divided among Herod’s sons— Archelaus, Philip, and Antipas—and eventually Roman prefects, there was less money in the central coffers for similar grand projects. Building projects in Judea were minimal, despite the fact that some parts of Galilee flourished. Perhaps as another sign of lost glory, none of the three sons received that coveted status of “king”.

Fig. 1.24: Dedication to Pontius Pilate found at Caesarea Maritima. 1st century CE. The inscription reads, “Pontius Pilate, Prefect of Judaea, [erected] a [building dedicated to the emperor] Tiberius.” The brackets indicate missing words.

Archelaus ruled as a tetrarch—meaning a sovereign of a quarter—over the regions of Judea, Samaria, and Idumea from 4 BCE to 6 CE. He had the reputation of being ruthless and vicious. During his reign, numerous protests erupted, but they were all met with swift and deadly responses. It is reported that, on one occasion, Archelaus crucified 2000 Jewish prisoners. His leadership became so intolerable that some of the elite Jews in Jerusalem sent a secret delegation to Rome, requesting that Archelaus be deposed. Augustus agreed and in 6 CE Archelaus was banished to Gaul (modern France). From that point onward, Roman governors ruled Judea, Samaria, and Idumea. The most well-known of these was Pontius Pilate, who sat in judgment of Jesus. In the book of Acts (23-26), we also read about governors Felix and Festus, who heard Paul’s case. One of the most corrupt governors was Florus, whose raid of the temple treasury was a contributing factor in a Jewish revolt that led to a war with Rome, and to the eventual destruction of the temple in 70 CE.

Map 1.4:Palestine under Herodian rule. Click on the image to expand.

The second son, Philip, ruled over the northern Hellenistic regions of Gaulanitis, Auranitis, Batanea, Trachonitis, Paneas, and Iturea from 4 BCE to 34 CE. Philip also engaged in building programs like his father (one of his most famous was the city of Caesarea Philippi), but compared to the other two sons, Philip is insignificant for the study of the New Testament.

The third son, Herod Antipas, was tetrarch over Galilee and Perea from 4 BCE to 39 CE. Of the three sons, he is mentioned the most in the New Testament, since he ruled over Jesus’ native region. In the Gospels, he is simply called “Herod.” As a result of his position, he was not directly under the administration of the Romans and could decide the fate of individuals, such as John the Baptist, without reference to anyone else (Matt 14:10; Luke 3: 20; 9:9; Mark 6:17; Ant. 18:116-19). Although Antipas paid tribute to Rome, the taxes that were collected by the temple establishment went directly to him.

It is difficult to know how supportive the Galileans were of the temple establishment. Scholars have argued in contrary directions. The saturation of Greco-Roman culture and the number of Gentile residents is hotly debated. Some argue that Galilee was primarily Jewish, whereas others argue that it boasted a large contingency of Roman officials and a substantial Gentile population. We know from the Gospels that Jesus’ ministry was focused on the rural Jewish population, but nothing is said about the ethnic demographic.

Fig. 1.25: View from the hill of Sepphoris.

Perhaps Herod’s most notable project was the rebuilding of the fortress city of Sepphoris, which was earlier destroyed by the Romans after a revolt led by Judah ben Hezekiah. It was located in the center of Galilee, about four miles northeast of Nazareth. It was also visible for miles around, because it was built on a hill. It may well be the city to which Jesus refers in the Sermon on the Mount, when he says, “you are the light of the world. A city set on a hill cannot be hidden” (Matt 5:14). Antipas made this city his capital in 4 BC (Ant. 18.27). During Jesus’ day, it was the largest city in Galilee and regarded by Josephus as its jewel. The rebuilding project included lavishly decorated residences for the elite, as well as Antipas’s palace, roads paved with limestone, a 4500-seat theater cut into the hillside, and two markets.

Fig. 1.26: Tetradrachma. Herod Agrippa with a diadem on the left. Tyche on the right. He was one of a few Jewish rulers to depict his image on a coin.

After Antipas was deposed in 39 CE, Caligula gave Galilee to Herod’s grandson, Agrippa I, and in 41 CE he was invested as king over the whole territory (i.e. Judaea, later called Palestine) that was formerly controlled by his grandfather, Herod the Great. Agrippa was raised “within the circle of Claudius” in Rome, and was more interested in the political affairs of the Jewish Diaspora than the mundane activities of the remote district of Galilee. He nonetheless took an active role in the politics of the temple and the high priesthood. After Agrippa’s death in 44 CE, Roman governors ruled over the kingdom. Eventually, the kingdom was given to Agrippa’s son, Agrippa II, who was the last of the Herodian kings.

1.7 The Jewish War with Rome

In the early 60s of the first century, uprisings and revolts were becoming commonplace. High tax loads, the corruption of the Roman governors, the distrust of the temple leadership, and the longstanding tensions between Jews and Gentiles brought a number of desperate Jews to the brink. Prominent men among the Jewish peasants arose and were urged to lead attacks against Roman strongholds, its citizens, and the elite. The atmosphere in Judea was tense—and in Galilee it was even worse.

One of the events that would lead to broad Jewish resistance was the crucifixion of thousands of Jews by the governor of Judea, Gessius Florus. In response, Jews known as “Zealots” infiltrated numerous Roman outposts and garrisons. Two of the installations that were occupied by the Jewish revolutionaries were Jerusalem and the fortress of Masada. In 66 CE, Rome declared all-out war against all Jewish revolutionaries.

The Jewish revolutionaries were formidable enemies. In one of the earliest battles, the Romans lost approximately 6000 men. The Roman Twelfth Legion was destroyed, which was an utter surprise and embarrassment to the Emperor and Roman administration (War 2.19.9 §555). The Romans, under the leadership of General Vespasian countered with a devastating offensive (60,000 troops), taking Galilee, Samaria, and many parts of Judea by 68 CE.

Fig. 1.27: Coin from 71 CE commemorating Vespasian’s suppression of the Jewish Revolt. Judaea is represented by a woman weeping under a palm tree. Ashmolean Museum. Oxford.

In Rome, the populace was not happy with the toll the war was taking. Nero was declared an enemy of the people and he soon committed suicide. Vespasian suspended the war, returned to Rome, and was made Emperor. His son Titus, who was also a General, was appointed to continue the onslaught—but both men knew that a victory was needed before much more time passed. Gathering additional troops in Alexandria, Caesarea, and Syria, Titus marched on Jerusalem and began a long drawn out attack on most of the remaining revolutionaries that were barricaded first in the city, and finally in the temple. After a five-month siege, Jerusalem was razed to the ground and the temple was destroyed.

Josephus’ account is detailed and graphic. He writes,

Now although any one would justly lament the destruction of such a work as this was, since it was the most admirable of all the works that we have seen or heard of, both for its curious structure and its magnitude, and also for the vast wealth bestowed upon it, as well as for the glorious reputation it had for its holiness; yet might such a one comfort himself with this thought, that it was fate that decreed it so to be, which is inevitable, both as to living creatures, and as to works and places also. However, one cannot but wonder at the accuracy of this period thereto relating; for the same month and day were now observed, as I said before, wherein the holy house was burnt formerly by the Babylonians. Now the number of years that passed from its first foundation, which was laid by king Solomon, till this its destruction, which happened in the second year of the reign of Vespasian, are collected to be one thousand one hundred and thirty, besides seven months and fifteen days; and from the second building of it, which was done by Haggai, in the second year of Cyrus the king, till its destruction under Vespasian, there were six hundred and thirty-nine years and forty-five days.

While the holy house was on fire, every thing was plundered that came to hand, and ten thousand of those that were caught were slain; nor was there a commiseration of any age, or any reverence of gravity, but children, and old men, and profane persons, and priests were all slain in the same manner; so that this war went round all sorts of men, and brought them to destruction, and as well those that made supplication for their lives, as those that defended themselves by fighting. The flame was also carried a long way, and made an echo, together with the groans of those that were slain; and because this hill was high, and the works at the temple were very great, one would have thought the whole city had been on fire. Nor can one imagine any thing either greater or more terrible than this noise; for there was at once a shout of the Roman legions, who were marching all together, and a sad clamor of the seditious, who were now surrounded with fire and sword. The people also that were left above were beaten back upon the enemy, and under a great consternation, and made sad moans at the calamity they were under; the multitude also that was in the city joined in this outcry with those that were upon the hill. And besides, many of those that were worn away by the famine, and their mouths almost closed, when they saw the fire of the holy house, they exerted their utmost strength, and brake out into groans and outcries again: Perea did also return the echo, as well as the mountains round about [the city,] and augmented the force of the entire noise. Yet was the misery itself more terrible than this disorder; for one would have thought that the hill itself, on which the temple stood, was seething hot, as full of fire on every part of it, that the blood was larger in quantity than the fire, and those that were slain more in number than those that slew them; for the ground did no where appear visible, for the dead bodies that lay on it; but the soldiers went over heaps of those bodies, as they ran upon such as fled from them. And now it was that the multitude of the robbers were thrust out [of the inner court of the temple by the Romans,] and had much ado to get into the outward court, and from thence into the city, while the remainder of the populace fled into the cloister of that outer court. As for the priests, some of them plucked up from the holy house the spikes that were upon it, with their bases, which were made of lead, and shot them at the Romans instead of darts. But then as they gained nothing by so doing, and as the fire burst out upon them, they retired to the wall that was eight cubits broad, and there they tarried; yet did two of these of eminence among them, who might have saved themselves by going over to the Romans, or have borne up with courage, and taken their fortune with the others, throw themselves into the fire, and were burnt together with the holy house; their names were Meirus the son of Belgas, and Joseph the son of Daleus (Jewish War 6.270-277).

Fig. 1.28: Bust of General and Emperor Titus, Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

The last stronghold of the Jewish revolutionaries was the fortress of Masada, high atop a cliff overlooking the Dead Sea some 1300 feet below. When the Romans arrived in 72 CE, they encircled the fortress, which was impenetrable from below. For months, the Romans built a ramp that was an engineering marvel. When the Romans finally penetrated the fortress in the spring of 73 CE, they found that 960 of the 967 inhabitants (men, women, and children) had committed mass suicide shortly before the Romans breached the doors. Josephus records the entire episode in the Jewish War 7.8-10 §252-406.

Fig. 1.29: The Fortress of Masada

With the destruction of the temple in 70 CE, the cultic rituals rooted in temple worship, especially the sacrifices, ceased. The Pharisees fled north and west, where they would start what would later develop into Rabbinic Judaism. The Sadducees disappeared, probably integrating into Roman urban life of other Jewish sects.

Some fifty years later, in 132 CE, when Emperor Hadrian erected a temple to the Roman god Jupiter on the site of the destroyed Jewish temple and prohibited the rite of circumcision, the Jews once again revolted. This time, they revolted under the leadership of a would-be messiah named Simon bar Kosiba. The famous Rabbi Akiba renamed him “bar Kokhba”, which in Aramaic means “son of a star,” referring to the messianic prophecy in Num 24:17. The war with the Romans lasted two years, until both Akiba and bar Kokhba were killed in 135 CE.

In the years that followed, the Romans rebuilt Jerusalem as a Roman city and banned Jews from ever entering it.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

“1 and 2 Maccabees.” The New Oxford Annotated Apocrypha. Edited by B. M. Metzger and R. E. Murphy. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Josephus. Antiquities of the Jews. 7 vols. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1930–65.

———. The Jewish War. 2 vols. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1927–28.

Whiston, William. Edited and Translated. The Works of Flavius Josephus: Complete and Unabridged. Peabody: Hendrickson, 1987.

Polybius. Histories. Loeb Classical Library, 6 vols. Translated by W. R. Paton. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1922-27.

Tacitus. The Histories. Loeb Classical Library, 2 vols. Translated by C. H. Moore. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1925.

Barrett, C. K. The New Testament Background: Selected Documents. 2d edn. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1989.

Kee, H. C. The Origins of Christianity. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1973. Especially pages 10–53.

Yadin, Y. Herod’s Fortress and the Zealots’ Last Stand. New York: Random House, 1967.

Secondary Sources

Alston, R. Aspects of Roman History AD 14-117. London: Routledge, 1998.

An introduction to the early Imperial period which corresponds to the New Testament writings. The first half provides a good introduction to the emperors from Tiberius to Trajan. The secnd half is a well-rounded introduction to Roman society.

Ando, C. Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

A description of the function of Roman political ideology in the unification of Rome and its provinces. This is a more advanced volume written from the perspective of social theorists.

Ben-Sasson, H. H., ed. A History of the Jewish People. Harvard University Press, 1976.

Very ambitious and highly informative compilation of Jewish history from the second millennium BCE to modern Israel, written by six Hebrew University scholars.

Bosworth, Albert Brian. Conquest and Empire: The Reign of Alexander the Great. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

One of the best accounts of the history written by a leading scholar.

Briant, P. Alexander the Great and his Empire: A Short Introduction. Translated by A. Kuhrt. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010.

Excellent insights into the personality of Alexander. Also useful for understanding the Persian opposiion.

Bruce, F. F. New Testament History. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1972.

A standard in the filed of New Testament studies for many years. Still a very useful tool.

Collins, J. J. Between Athens and Jerusalem: Jewish Identity in the Hellenistic Diaspora. 2d edn. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2000.

An excellent and highly readable discussion of Judaism in the context of Hellenism.

Crossan, J. D. and J. L. Reed. In Search of Paul: How Jesus’s Apostle Opposed Rome’s Empire with God’s Kingdom. San Francisco: Harper, 2004.

Steeped in archaeological data, the authors demonstrate how Paul confronted the politics and culture of the empire in his missionary travels. A good example of how Roman background material can inform the reading of the New Testament. Clearly written and contains numerous illustrations and photos.

Goodman, M. Rome and Jerusalem: The Clash of Ancient Civilizations. London: Penguin, 2007.

A detailed account of how the relationship between Jews and Romans changed after 70 CE.

Horsley, R. A. Galilee: History, Politics, People. Valley Forge, PA: Trinity Press International, 1995.

A valuable analysis of the political and social dimensions of both rural and urban Galilee. The interpretations of the data raise provocative questions. Excellent summary of prior works on Galilee.

Horsley, R. and J. S. Hanson. Bandits, Prophets and Messiahs: Popular Movements in the Time of Jesus. Harrisburg: Trinity Press International, 1999.

A highly readable and well documented survey of passive and active revolutionary movements in early Judaism. Provides a valuable context for understanding Jesus’ ministry.

Jeffers, J. S. The Greco-Roman World of the New Testament Era. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1999. Very accessible. Good introduction.

Rhoads, D. M. Israel in Revolution, 6–74 C.E.: A Political History Based on the Writings of Josephus. Philadelphia: Fortress, 1976.

An excellent treatment of the Jewish war with Rome.

Rocca, S. Herod’s Judaea: A Mediterranean State in the Classical World. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2008.

A valuable look into the relationship between King Herod, who modeled his reign after Alexander the Great and Augustus, and his Jewish subjects in Judaea.

Rostovtzeff, M. I. Social and Economic History of the Roman Empire. 2 vols. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1957.

This is still a valuable and comprehensive source for understanding the transformational policies of the empire and their impact on the provinces. It is rich in plates and illustrations.

Schürer, E. The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ (175 b.c.–a.d. 135). Vol. 1. Revised and edited by G. Vermès and F. Millar. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1973.

This is an encyclopedic account of the Jewish history. For advanced readers.

Schiffman, L. From Text to Tradition: A History of Second Temple and Rabbinic Judaism. Jersey City: Ktav, 1991.

A fine treatment on the writings of the Second Temple Period.

Shipley, G. The Greek World After Alexander 323–30 BC. London: Routledge, 2000.

A readable account of the social fabric of Hellenism.

![Fig. 1.24: Dedication to Pontius Pilate found at Caesarea Maritima. 1st century CE. The inscription reads, “Pontius Pilate, Prefect of Judaea, [erected] a [building dedicated to the emperor] Tiberius.” The brackets indicate missing words.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d39a48e8593e000010788eb/1566725475660-SFSNEDLTJ5S8TAHTAJHX/Dedication+to+Pontius+Pilate+found+at+Caesarea+Maritima.+1st+century+CE..jpg)