Module Fifteen

PAUL AND HIS LETTERS

15.1 Introduction

Artist's depiction of Paul the Apostle.

Paul is often called the founder of Christianity, and for good reason. Whereas Jesus’ ministry was oriented toward the restoration of Israel, Paul’s focus was much broader. Identifying himself as “an apostle to the Gentiles” (e.g. Rom 11:13), Paul traveled throughout the Roman Empire to share his belief that God has come to reconcile the world to himself through his son, Jesus the Messiah. Paul’s message to his Gentile converts centered on the faithfulness to Christ without obligation to Jewish identity rituals, such as circumcision and dietary laws. His movement away from traditional Jewish practices formed the basis for the beginning of a new religion that we today call Christianity.

Next to Jesus, the Apostle Paul is the most prominent figure in the New Testament. In addition to being one of the main personalities in the book of Acts, Paul was a prolific author. Thirteen of the twenty-seven writings of the New Testament are attributed to him. Even though most scholars are skeptical that Paul wrote all of them, they are nevertheless commonly called the Pauline Letters or the Pauline Corpus. The thirteen letters bearing Paul’s name are commonly divided into “disputed” letters and “undisputed” letters. While there is disagreement about which letters should be classified as “disputed,” there is agreement that the “undisputed” letters include Galatians, Romans, 1st and 2nd Corinthians, Philippians, Philemon, and 1st Thessalonians. All of these would have been written between 50 CE and the mid-60s, when Paul was executed under the emperor Nero.

This chapter is a general introduction to the study of Paul’s life and thought in modern scholarship. While important characteristics of ancient letters are introduced at the end of the chapter, Paul’s individual letters are discussed in subsequent modules, which are grouped into “Earliest Letters,” “Major Letters,” and “Prison Letters.”

15.2 Paul’s Thought in Modern Scholarship

Although Paul’s contribution to the formation of Christianity is enormous, his teachings have not been without controversy in his context and ours. In the ancient world, contemporary Jews were outraged that he believed in a crucified messiah. His fellow Jewish-Christians were incensed that he did not require Gentile converts to adopt Jewish rituals. Today, some readers claim that Paul’s views on homosexuality and the role of women in the church are harmful. His theological arguments, which largely focus on the implications of the suffering and resurrected Christ, have generated countless debates. Love him or hate him, he cannot be ignored if one wants to understand the origins of Christianity.

Albert Scweitzer

Before we embark on introducing Paul and his letters in this chapter and the ones that follow, it is important to get a glimpse of the big issues that have dominated Pauline studies for over a century. The modern study of Paul can be traced to the influential work of Albert Schweitzer in the early part of the twentieth century. Schweitzer collected and analyzed prior studies on Paul and clearly summarized their foci into two simple and interrelated questions: (1) Was Paul a Jewish or Greek thinker? And (2), what is the central focus of Paul’s theology? Was the center “justification by faith,” which implied a critique of Judaism, or was the center “being in Christ,” which was consistent with Judaism? Schweitzer’s choice was uncompromising. Paul was thoroughly Jewish, believing that God has dramatically encountered the world through Jesus the Messiah. Thus, argued Schweitzer, Paul was an apocalyptic Jew who expected the imminent end of the age. Schweitzer effectively turned Paul from a dogmatic Hellenistic theologian to a Jewish mystic who focused on Christian identity. The implications are huge. How we understand the center of Paul’s identity and theology will affect how we interpret key passages in his letters.

Info Box 1: Albert Schweitzer

Albert Schweitzer was an astonishing and accomplished figure. In addition to his work on Paul, he changed the direction of historical Jesus research (see Chapter 8); he was music scholar and organist; he was missionary physician; and he was the recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1952 for his ethical philosophy, termed “Reverence for Life,” which he saw as the underlying value system of civilization. It served as the foundational concept for the establishment of the Albert Schweitzer Hospital in what is today the African republic of Gabon.

Rudolph Bultmann

Since Schweitzer’s monumental studies in the early part of the twentieth century, numerous scholars have contributed to the way we understand Paul today. A few have been particularly influential. The first is Rudolf Bultmann, who we already encountered in Module 8 (“The Historical Jesus”). Both Schweitzer and Bultmann wrestled with the relevance of the New Testament in the Modern period. In his New Testament Theology, Bultmann presents Paul as a thinker who reflects his broader Hellenist context. As an apostle to the Gentiles, Bultmann believed that Paul abandoned and even resisted Jewish categories and rituals, especially those pertaining to the Law, because they interfered with the new life of faith offered in Christ. At the centre of Paul’s theology was the plight of the human condition, which Bultmann called “man under the law.” Appealing to Romans 5-8, which he saw as the hub of Paul’s thinking, Bultmann argued that the decision (i.e. faith) to follow Christ delivers humanity from its plight. In so doing we are justified by faith and freed from legalism, religious pride and social constraints to be authentic and free human beings, which was the true meaning of Christian existence.

Bultmann’s enormous influence in academic circles over several decades was met with formidable resistance in the post-war works of W. D. Davies and Ernst Käsemann. In his Paul and Rabbinic Judaism, Davies returned to Schweitzer’s claim that Paul is best understood within the context of Judaism instead of Hellenism, but not apocalyptic Judaism. Davies argued that Paul was a Jewish rabbi who believed that the anticipated new age had already arrived in Jesus. Paul saw his mission as expanding the new people of God who were not governed by the old law, but by a new law that is rooted in Christ.

Ernst Käsemann

By reading Paul within a rabbinic context, Davies affected a shift in attitude toward Judaism among New Testament scholars who had previously characterized it as a religion of works, legalism, and prejudice. Judaism became a much more favorable context for understanding Paul and his thought. Davies’ post-war context cannot be underestimated. The Holocaust significantly shifted the focus of New Testament scholarship. Instead of viewing Hellenism as the influential context of early Christianity, scholars began to appeal more deliberately to early Judaism. Ernst Käsemann’s contribution attempted to bring about a synthesis of his predecessors, particularly those of Schweitzer and Bultmann. Like Bultmann, he argued that at the center of Paul’s theology is his teachings on justification by faith, which was an antidote to religious legalism and human pride; and, like Schweitzer, he argued that the best context for understanding Paul is apocalyptic Judaism. God had come in Christ, defeated evil, and justified the ungodly, affecting equality among human beings. Käsemann recognized that Paul—like the Old Testament prophets, John the Baptist, and even Jesus—criticized Judaism from within and not as an outsider.

In recent years the work or E. P. Sanders, especially his Paul and Palestinian Judaism, has set a new direction in Pauline studies. Instead of locating Paul within rabbinic Judaism as his teacher W. D. Davies had done, Sanders broadened the Jewish context to include traditions that were common in first-century Palestine, relying not only on rabbinic literature, but also the writings of the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Pseudepigrapha, the Apocrypha, and Josephus. What Sanders found changed the perception of Paul’s interaction with early Judaism among New Testament scholars. Sanders convincingly showed that Judaism was not a religion of legalism or works-oriented righteousness as was commonly assumed. Rather, it was a religion based on God’s grace. Jews observed the laws, which were given by God as a covenantal initiative, out of gratitude. Observance was a response to grace, not to earn salvation. Thus, in contrast to the majority reading, Paul was not attacking a legalistic religion. His problem with Judaism was that it did not accept the new way of being in Christ. Like Schweitzer, Sanders argued that the center of Paul’s theology was not justification by faith, but “participation,” by which he meant a union with Christ.

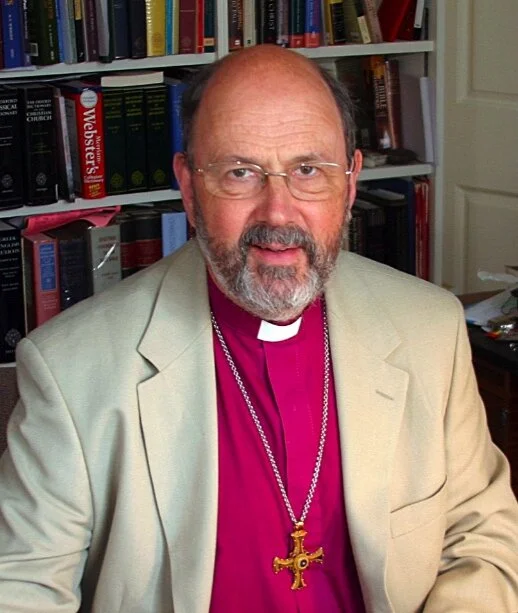

N. T. Wright

Whether one agrees or disagrees with Sanders’ conclusions, he remains a necessary conversation partner who has shifted our perspective on Paul. Today, scholars who agree and disagree with Sanders must interact with him. One of his most prolific conversation partners today is N. T. Wright, who has extended the raw ideas of Sanders into a more coherent and exegetically substantiated theology of Paul. For Wright, Paul brings a new vision of reality—of God, the world, and human identity—to Roman world. To the pagans, who are his primary objective, he offers Christ as the revelation of the one true god who displaces all other deities. In so doing, Paul undermines the pagan vision of reality and replaces it with the Jewish one, albeit centered in Christ. To his fellow Jews, Jesus the crucified Messiah is the revelation of the God of Israel who fulfills the failed vocation of Israel in bringing salvation to world. In Wright’s terms, Paul’s Christ is the reconstitution of Israel who, through his obedience and vindication in the resurrection brings the world into union with God.

Info Box 2: Criticism within Judaism

The idea of Paul standing within Judaism as a critic of his own religion is consistent with what scholars have found in the Jewish literature of the first century. Jewish groups commonly criticized each other for different beliefs, interpretations of scripture, rituals, ethical practices and social affiliations. Chapter four contains more detail on these differences. For example, in the Dead Sea Scrolls, which are commonly attributed to the Jewish sect called the Essenes, rival Jewish groups are severely criticized for their corrupt Temple practices and misreading of the scriptures. Josephus also contains numerous passages explaining how the Pharisees and Sadducees varied drastically in their beliefs and criticized each other. In addition to many other examples, the teachings of Jesus can also viewed as a critique of his Jewish contemporaries.

15.3 Paul’s Life: The Sources

Unlike the evangelists, whose Gospels are anonymous and have no autobiographical information, we know something about the background and life of the author of the Pauline letters. In fact, we know more about the Apostle Paul than any other New Testament writer, which gives us a rare biographical context for understanding his writings.

Our information about Paul comes from three major sources. The first and most credible information comes from his letters, which contain sporadic autobiographical bits of data. The second major source is the Book of Acts, where Paul appears as the major character. Although Acts is written at least two decades after Paul’s death, it may preserve some historical information about him especially since its author, Luke, may have been Paul’s traveling associate, as we have seen in the previous chapter. In any case, the use of Acts for reconstructing the life and teachings of Paul has been controversial. This is why scholars sometimes speak about the “Pauline Paul” and the “Lukan Paul.” Despite one’s view of the genre of Acts, the historian must exercise caution so as not to conflate the sources uncritically. The third source is not an individual text, but a collection of post-New Testament Christian texts and traditions. These may preserve some historical information, like the claim that Paul was executed in Rome. From these sources we learn, for example, that Paul was a Jew born outside of the land of Israel, that he was well educated, that he travelled throughout the Roman Empire, and that he was a Pharisee, the school of thought that we encounter so often in the Gospels. Let’s take a look at Paul’s life in more detail.

15.2 The Pre-Christian Paul

Paul’s conversion to Christianity is an important milestone for the study of Paul’s life and teachings. While all of his letters were written after his conversion, scholars have been interested about the relationship between Paul’s pre-Christian Jewish life and his newfound faith in Jesus Messiah. Was there continuity or discontinuity? Did the Christian Paul see himself still as a Jew? If so, how? In seeking to understand the life of Paul, we will follow this common distinction between the pre-Christian Paul and the Christian Paul.

15.2.1 Paul’s Birth and Youth

The only autobiographical data that we have for estimating the date of Paul’s birth is a meager reference in Philemon 9 where Paul calls himself “elderly.” In early Jewish tradition, being elderly would have referred to a person being in their late 50s or early 60s. If we date Philemon as early as 53 CE, then he would have been born close to the time of Jesus, approximately 6-4 BCE. If, however, we date Philemon in the early 60s (see Module 18), then he would have been born about 10 years later.

Info Box 3: List of Ages in Jewish Tradition

In a rabbinic list that is dated from the end of the first century CE to the end of the second, 60 years of age is associated with being an elder. Avot 5:21 of the Mishnah reads, “At 5 years old one is fit for the Scriptures, at 10 for the Mishnah, at 13 for the fulfilling of the commandments, at 15 for the Talmud, at 18 for the bride chamber, at 20 for pursuing a calling, at 30 for authority, at 40 for discernment, at 50 for counsel, at 60 for to be an elder, at 70 for grey hairs, at 80 for special strength, at 90 for a bowed back, at 100 a man is as one that has already died.”

Location of Tarsus

Luke offers more potential biographical data. In one of Paul’s speeches in Acts, he says “I am a Jew, from Tarsus in Cilicia, a citizen of an important city” (21:39). None of Paul’s letters identify him with Tarsus, though there may be a sliver of evidence that he had some connections with the city when he journeys to the “districts of Syria and Cilicia” (Gal 1:21) after his first visit to Jerusalem. Going to Syria was understandable given its early Christian presence, but Cilicia is perplexing, unless Paul had close ties there. Though we may be reasonably confident that Tarsus was the location of Paul’s birth and the reception of Roman citizenship, we can be less certain about how long he actually lived in there. Some scholars claim that Paul was only born in Tarsus, but spent most of his formative years in Jerusalem. This view is largely based on a historical reading of Paul’s speech to an angry mob of Jews at the Temple more historically, where he says, “I am a Jew, born in Tarsus in Cilicia, but brought up in this city at the feet of Gamaliel, educated strictly according to our ancestral law” (Acts 22:3).

It is unlikely that “this city” should be associated with Tarsus, and more likely refers to Jerusalem (where the speech is being given) since Luke is trying to draw parallels between Paul and the crowd. Paul’s nephew (literally “the son of Paul’s sister”) is also mentioned as being in Jerusalem, which may indicate that Paul’s family moved from Tarsus to Jerusalem (Acts 23:16). Furthermore, Gamaliel is considered to be a respected teacher in Jerusalem, both in biblical (Acts 5:34-39) and extra-biblical accounts (m. Soṭah 9:15). Finally, Paul claims to be lacking rhetorical training and eloquence (1 Cor 1:17; 2 Cor 11:6), which suggests that he was not influenced by the Tarsus schools of rhetoric in his formative years were. This claim, however, must be held in tension with the nature of his letters, which often employ and adapt established rhetorical conventions that would have been taught in Tarsus.

Tarsus ruins

Other scholars argue that Paul grew up in Tarsus and was thoroughly influenced by Greek culture and education as is indicative by his letters. In addition, some portions of Paul’s letters make it difficult to say that he had been a resident of Jerusalem from an early age. In his letter to the Galatians, Paul claims that three years after his conversion, “I was still unknown by sight to the churches of Judea that are in Christ” (1:22). If Paul’s formative years were spent in that area, it would be surprising that the local churches would only know him by reputation.

Info Box 4: Was Tarsus a Greek City?

Tarsus was located on major trade route that connected eastern part of the empire with the western part. It’s residents, however, may have been much more eastern in their customs. Dio Chrysostom (c. 40-115 CE), a Greek orator, philosopher, and historian, described the residents of Tarsus in unflattering terms as being more Phoenician than Greek, particularly in their musical and fashion tastes. With regard to female attire, he writes that the women of Tarsus follow “a convention which prescribes that women should be so clothed and conduct themselves when in the streets that no one might see any part of them, neither their face nor the rest of the their body” (Discourses 33.48).

15.2.2 Paul the Hebrew

When Paul writes about his own identity, he uses Jewish terms and phrases. In Phil 3:5, Paul describes himself as “circumcised on the eighth day, a member of the people of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Hebrew born of Hebrews; as to the law, a Pharisee.” Similarly, in 2 Cor 11:21 Paul identifies himself as a “Hebrew,” an “Israelite” and a “seed of Abraham.” While these terms appear synonymous, Paul’s selection of these terms in such close proximity to themselves may well imply that each communicates a different nuance.

Paul’s self-designation as a “Hebrew” carries religious and ethnic overtones, but also has a linguistic connotation. Paul likely implies that he spoke Hebrew (or perhaps Aramaic, a cognate language very closely related to Hebrew). If this is the case, then it is consistent with Luke’s reference to Paul speaking to a crowd of Jews in Hebrew (Acts 21:40). Paul’s reference to being a “Hebrew born of Hebrews” implies that he acquired his knowledge of Hebrew from his parents who were not proselytes, but born Jewish. Their familiarity with Hebrew and/or Aramaic indicates that despite their residence in the Diaspora, their roots were in Palestine where they would have learned the language, since there was little use for Semitic languages outside of that region. Jews in the Diaspora usually spoke Greek along with whatever language was native to their specific region.

Arch of Titus (detail showing Menorah)

Paul’s self-designation as a “Hebrew” may also have a rhetorical function in response to his detractors and opponents within the early Christian community in Jerusalem. According Acts 6:1, the early church appeared to have been divided into “Hebrews” and “Hellenists.” Since Jesus’ disciples all came from Galilee, they would have been associated with “Hebrews” who had a much closer bond to Palestine, and hence to Jesus, than the “Hellenists.” By identifying himself as a “Hebrew,” Paul links himself with the earliest followers of Jesus.

Info Box 5: Paul’s Parents.

The New Testament is silent on the origins of Paul’s family. Jerome (347-420), who is best known for translating the Bible into Latin (called the Vulgate), records a tradition that traces Paul’s family to Gischala. Jerome writes, “We have heard this story. They say that the parents of the Apostle Paul were from Gischala, a region of Judaea and that, when the whole province was devastated by the hand of the Rome and the Jews scattered throughout the world, they were moved to Tarsus a town of Cilicia; the adolescent Paul inherited the personal status of his parents” (Commentary on Philem. 23-24). About five years later, Jerome makes it clear that Paul was born in Gischala (contrary to modern opinion), writing “he was of the tribe of Benjamin and of the town of Gischala in Judaea, when the town was captured by the Romans he migrated with his parents to Tarsus in Cilicia” (Famous Men 5). Both translations are taken from Jerome Murphy-O’Connor.

15.2.3 Paul the Roman Citizen

Paul makes no reference to Roman citizenship in his letters. All of the references are in Acts. For this reason along with reference to his beatings by Roman soldiers, a few scholars doubt that Paul was a citizen. Most scholars, however, agree that Paul was indeed a Roman citizen since there is no indication that Luke invented Paul’s status for rhetorical or propagandizing reasons. Luke mentions Paul’s citizenship several times in Acts.

For example, in Acts 16, Paul and Silas exorcise a demon from a slave girl, which angers her owners because they had been profiting financially from her abilities to tell fortunes. The owners accuse Paul and Silas of unlawful teachings and drag them before the Roman magistrate, who has them stripped, flogged, and imprisoned. The next morning, when they are released, Paul reveals that since he and Silas are Roman citizens, they had been treated illegally since they were not given a trial. This alarms the officials and they personally escort the two men out of the prison.

A second example is found in Acts 22-23 when Paul is arrested for inciting an angry crowd, which takes exception to his preaching. In order to make sense of the commotion, a Roman Tribune orders that Paul be arrested and flogged. After Paul is bound, he asks the Centurion, “Is it legal for you to flog a Roman citizen who is not condemned?” The Centurion reports Paul’s status to the Tribune and the immediately cease with the punishment. In the morning the Tribune brings the matter before the Jewish officials who convene a council. When the Tribune hears that the Jewish leaders have become incensed with Paul and vow to kill him, he send soldiers to rescue Paul and take him to the Governor for a fair hearing.

The last example is found in Acts 25 when Paul is being tried before Governor Festus in Caesarea. When the Jews who accuse Paul of wrongdoing want him sent to Jerusalem for the trial, Paul appeals to the Governor that he wants to be tried before the emperor in Rome. After conferring with his council, Festus replies, “You have appealed to the emperor; to the emperor you will go.” Paul’s request may be surprising to modern readers, but as a Roman citizen, he would have had the right to appeal to the emperor.

Info Box 6: The Law Against Flogging a Roman Citizen

In one of the many moral laws (named lex Julia, after the Julian family) instituted by Emperor Augustus in 18-19 BCE, flogging of a citizen was condemned. This law reads, “Also liable under the lex Julia on vis publica is anyone who, while holding imperium or office, puts to death or flogs a Roman citizen contrary to his right of appeal, or orders any of the above mentioned things to be done, or puts (a yoke) on his neck so that he may be tortured” (Digest 48.6.7). Translation is taken from Jerome Murphy-O’Connor. This law, however, was not always followed. There are several references in ancient sources of Roman citizens being beaten and even executed. One’s wealth and prestige would have played a role in a magistrate’s decision as well, which may suggest that Paul had both.

Roman citizens would carry some form of identification that proved their Roman citizenship (either a birth certificate or other certificate of citizenship). Although neither Paul nor Luke make any mention of this documentation, it is likely that Paul produced some proof of citizenship when he claimed his Roman rights before the officials. Travelers like Paul would usually carry their citizenship documentation with them, but in cases where the document could not be produced, the challenge to prove one’s citizenship became a very difficult task. New documentation would have to be ordered from the applicant’s home region.

How Paul’s family acquired citizenship is unknown, but it has not detracted from speculation. A common reconstruction links the family’s citizenship to their residence in Tarsus. After Caesar’s Civil War (49-45 BCE), residents of Tarsus received grants of citizenship for supporting Julius Caesar, who was the victor. One of these residence owned Paul’s father as a slave. When Paul’s father was released, he was granted partial citizenship. Paul inherited his father’s citizenship with even greater privileges, as was customary for children of Roman citizens.

15.2.4 Paul’s Education

Like many Jewish children, Paul would have been exposed to the scriptures and their interpretive traditions at home in a synagogue context. Growing up in the diaspora, he would have found himself straddling two worlds. One foot would have been planted within his Jewish minority sub-culture and the other would have been planted in the broader pagan culture. If Paul grew up in a family of higher social standing, he would have been trained in the basic skills of reading, writing, and arithmetic.

Reenactment photograph of ancient scribal students.

Paul undoubtedly knew Hebrew and Aramaic, but all of his letters were composed in Greek. As self-acclaimed “Apostle to the Gentiles,” it is not surprising that Paul writes in Greek, which was the most widely spoken language in the Mediterranean basin. Paul was well educated in the Jewish scriptures. Throughout his letters, Paul demonstrates a close familiarity with the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, known as the Septuagint (see Module 4). His letters contain almost ninety quotations and countless allusion, which are used to reinforce his arguments. Biblical figures, such as Abraham, Moses, and David were particularly important in the formation of his theological thinking because they served as analogies to Jesus.

While Paul’s religious experiences shaped his engagement with scripture, it was not a one-way street. Paul did not merely take his new beliefs about Jesus and use the scriptures to support them. Instead, Paul seems to have engaged in the dialectical process between past and present. His devotion to Jesus altered the way he read scripture. Conversely, scripture shaped his understanding of Jesus.

Info Box 7: Remembering Jesus “in accordance with the scriptures”

For Paul, Jesus seems to have been primarily remembered for what happened at the end of his life: his death and resurrection. Paul remembered Jesus first and foremost as the crucified and resurrected Christ. Scripture largely shaped his inherited remembrances. Like other early Christians, Paul believed that Jesus’ death and resurrection were “in accordance with the scriptures” (1 Cor 15:3-4). While many modern readers have trouble believing that the Old Testament texts predicted the life and death of Jesus, there is a sense that Jesus’ death and resurrection really were “in accordance with the scriptures” as the church’s remembrance of these events was created (and re-created) in continual conversation with scripture. For Paul and his contemporaries, meaning and significance were the primary aims, not reconstruction.

Paul was also well educated in Greco-Roman literature, philosophy, and the art of rhetoric. His letters indicate proficiency in Greek and cohere with established literary and philosophical standards. They clearly convey that Paul underwent formal philosophical and rhetorical training. While Paul tells us nothing about his youth, most scholars claim that his formal education began in Tarsus, which was well known for its devotion to higher education, especially its schools of rhetoric. The Greek geographer Strabo, who was a contemporary of Paul’s, describes the educational scene.

The people at Tarsus have devoted themselves so eagerly, not only to philosophy, but also to the whole round of education in general, that they have surpassed Athens, Alexandria, or any other place that can be named where there have been schools and lectures of philosophers. But it is so different from other cities that there the men who are fond of learning are all natives, and foreigners are not inclined to sojourn there; neither do these natives stay there, but they complete their education abroad; and when they have completed it they are pleased to live abroad, and but few go back home” (Geography, XIV.5.13; LCL).

If Strabo is correct that the residents of Tarsus commonly completed the remainder of their education elsewhere, then it may provide some context to Paul’s educational journey. Paul probably began his formal education in his hometown, studying oratory or rhetoric, which would have included theories of discourse, letter writing, and the speeches of great masters. For some unknown reason Paul left Tarsus and resumed his education in Jerusalem, probably at the age of 20 when his four-year training in rhetorical ended. Paul tells us nothing about his time in Jerusalem, but Luke fills the void in a small way when he has Paul respond to his Jewish adversaries in Jerusalem, “I am a Jew, born in Tarsus in Cilicia, but brought up in this city at the feet of Gamaliel, educated strictly according to our ancestral law, being zealous for God, just as all of you are today” (Acts 22:3; cf. 26:4). If Luke is correct, then Paul was trained under the tutelage of a renowned teacher in the Pharisaic tradition, named Gamaliel I (or the Elder), who may have been the successor of the famous rabbi Hillel (m. Aboth 1.18). Along with intensive study of the scriptures, Paul would have learned the numerous oral traditions that identified the Pharisees.

While there is broad agreement that Paul was trained in the Pharisaic tradition, some scholars doubt that he studied under Gamaliel because there is no mention of it in his letters. In addition, Paul’s violent conduct toward Christians (Gal 1:13; Acts 8:1-3) prior to his conversion is inconsistent with Gamaliel’s temperate and wise portrayal (Acts 5:33-39). If Paul did not study under Gamaliel, why would Luke say that he did? In short, it could have had rhetorical value. Since Acts is not a modern history, but an apologetic history (see Module 13), events were selected and created to demonstrate the superiority of Christians and their message over and against their (often Jewish) opponents. After all, the Christian message was preached as the fulfillment of Judaism. Paul’s association with Gamaliel may have been Luke’s way of establishing Paul’s credibility as a Jewish scholar in the face of Jewish opposition.

Info Box 8: “I am unskilled in speaking”

Paul’s disclaimer in 2 Cor 11:6 that he is unskilled in speech cannot be taken at face value. When the broader argument is taken into account, Paul is directing his self-assessment at his detractors, whom he sarcastically calls “super apostles.” Paul purposely uses “unskilled speech” so that the faith of Corinthian Christians “might rest not on human wisdom, but on the power of God’ (1 Cor 2:5). Unlike his opponents, Paul did not want to use persuasive techniques to proclaim the gospel. Paul’s restraint conveys maturity and confidence, which may have been learned from Stoic teachers in Tarsus.

15.2.5 Paul the Pharisee

Modern reenactment photo of Pharisees

Paul attests to being a Pharisee in Phil 3:5, but he does not tell us why he joined the group. Paul’s description of his youth in Gal 1:14 that he “advanced in Judaism beyond many among my people of the same age” and was “more zealous for the traditions of my ancestors” has a Pharisaic ring to it, but it most likely functions as a contrast to Jewish Christian missionaries who are attempting to undermine him. There is no indication here of Paul having parents who were Pharisees. Luke’s attestation that Paul was a “son of Pharisees” in Acts 23:6 is difficult to accept at face value for most scholars because there is a lack of evidence to support the presence of Pharisees in the diaspora before 70 CE. Luke may simply be using the attestation rhetorically to connect Paul more closely with Jerusalem. It is easy to imagine the Paul joined the Pharisees out of his own volition because he was attracted to their rigorous attention to scripture and oral tradition.

Our knowledge of the Pharisees is limited because the sources closest to the time of Paul, namely the New Testament and Josephus, portray them in a biased fashion (see Module 4). In the Gospels they are generally portrayed negatively as opponents of Jesus, who rarely have the last word. In Josephus, it is quite the opposite. They are portrayed positively as a group that cultivates social responsibility, kindness, and peace. Apart from these biases, both sources are helpful for better understanding this group. We can be fairly confident that the Pharisees were very well educated in the interpretation of scripture, the oral traditions, and the practice of Jewish rituals. Josephus makes this explicit. The Gospel writers imply that the Pharisees are well educated, despite their inability to keep with Jesus. And Paul, as a Pharisee, clearly conveys his knowledge of scriptures in his letters.

Paul as a Pharisee would not have been part of the governing class. While the Pharisees had political interests, they would have been one of several groups that competed for a voice in Jewish society. Paul would have sought influence with the ruling class (primarily the Sadducees) in order to achieve the Pharisees’ social and religious ideals. Paul was probably situated within the retainer class, which was subordinate to the ruling class. Individual Pharisees, however, became important leaders due to their prominence within the group or on the basis of family status. Gamaliel was probably one of these leaders. In Acts, Luke describes Gamaliel as a Pharisaic member of the Sanhedrin who was highly respected, persuasive and thoughtful in decision-making (Acts 5:33-39). Luke’s exalted descriptions are consistent with the high praise of Gamaliel in the Mishnah, which records that “When Rabban Gamaliel the Elder died, the glory of the Torah came to an end, and cleanness and separateness perished” (m. Sotah 9:15).

Info Box 9: The Wisdom of Gamaliel

Acts records that when the Sanhedrin was convened to decide the fate of Peter and the other apostles who were preaching about Jesus in the Temple courts, Gamaliel advised the Sanhedrin privately. His speech compares the nascent Christian movement to two popular revolts that were crushed by the Romans (Acts 5:35-39). Gamaliel evaluates the legitimacy of Jewish revolutionary groups on the basis of their political success. If they are of human origin, then they will not be able to sustain themselves and will be obliterated by the Roman, but if they are of God, then they will succeed and will not be stopped. Gamaliel’s speech convinces the Sanhedrin that the disciples of Jesus should be released, but not before they are flogged (Acts 5:40).

Once gain, however, not all scholars are convinced that Luke’s account of Gamaliel is historically accurate. A renowned Jewish teacher named Gamaliel probably existed in the first century, but he may not have addressed the Sanhedrin in the way that Luke records. Many scholars believe that Gamaliel’s speech in Acts 5:35-39 is a rhetorical construct that uses a prominent Jewish member of the Sanhedrin to indirectly legitimize the nascent Christian movement. Gamaliel’s speech implies that since the movement is not crushed by the Romans, like previous revolts, but actually expands (Acts 6:1), it must be divinely commissioned. Luke uses the character of Gamaliel to subvert Jewish opposition to the expansion of Christianity.

15.2.6 Was Paul Married?

Debate about Paul’s marital status often arises in discussions about Paul’s view of women and his view of remarriage. When he wrote 1 Corinthians, he clearly identifies his status as being single, saying “To the unmarried and the widows I say that it is well for them to remain unmarried as I am.” (1 Cor 7:8; cf. 9:5). What is not clear, however, is whether Paul ever was married. If he was, was he a widower? Was he divorced? Or, was he separated? The opinion among scholars has shifted over the decades. Whereas at one time it was common to assume that Paul was never married, today most scholars agree that at some point in his life he was. While it is possible that Paul never married, it is more likely that he was in light of the high value that Jews placed on marriage. The importance of marriage is found in both scripture (e.g. Gen 1:28; 38:8-10; Deut 25:5-10) and later rabbinic traditions, which recommended that a young man be married between 18 and 20 years of age (e.g. Mishnah, Aboth 5:21). If Paul converted to Christianity around 40, it is conceivable that he had been married and even had children.

While there are cases of men remaining celibate in early Judaism, the vast majority would have been married. Many of those marriages would have been arranged. Given that Paul identifies himself as a traditional Jew in the Pharisaic tradition, he would have most likely submitted to the social requirements and expectations to have a family.

Info Box 10: What Happened to Paul’s Wife?

While speculation abounds, one interesting proposal links Paul’s pre-conversion persecution of Christians with the death of his wife and children. As a Pharisee, Paul would have believed that events occurred for a reason within God’s providence. If Paul’s family suffered a tragic death by means of an accident, an earthquake, or a plague, then Paul would have assumed that somehow God had a hand in it. Jerome Murphy-O’Connor explains that “one part of his theology would lead him logically to ascribe blame to God, but this was forbidden by another part of his religious perspective, which prescribed complete submission to God’s will. If his pain and anger could not be directed against God, it had to find another target” (65).

Whatever Paul’s personal circumstance, he held a very high view of marriage (Rom 7:1-4; 1 Cor 7:10-11). He allows for celibacy as an acceptable Christian lifestyle, but warns that it can easily lead to sexual immorality. If celibacy is a struggle, Paul recommends marriage, though he is adamant that those who choose to marry must do so with other believers (2 Cor 6:14). Otherwise, the risk of turning away from one’s Christian faith is increased (1 Cor 7:39). In cases where one spouse converts and the other does not, they should attempt to stay together (1 Cor 7:12-16). For Paul, celibacy is desirable because it has the benefit of allowing a believer to give his or her undivided attention to Christ.

15.2.7 Persecutor of Christians

Prior to his conversion, Luke describes Paul as a zealous Pharisee who persecuted Christians. Paul’s antagonism is established early. When Paul was a “young man,” Luke writes that Paul not only approvingly witnessed the gruesome execution of a Christian named Stephen, but also looked after the coats of the executioners (Acts 7:58-8:1; 22:20). From that moment on, Luke implies that Paul began a persecution campaign against Christians, searching homes, and dragging off both men and women to prison (Acts 8:3). Paul is, however, not content to ravage the church in Jerusalem. He asks the high priest to issue him letters to the synagogues at Damascus so that he could bring Christian Jews back to Jerusalem for trial (Acts 9:1-2). Paul’s persecution activity included arresting and imprisoning Christians (Acts 22:4), voting for their execution during hearings (Acts 26:10), and trying to cause them to commit blasphemy in the synagogue (Acts 26:11). How did Paul achieve such authority to persecute, arrest, and even vote to have Christians executed (Acts 26:10)? Since capital cases were under the jurisdiction of the Sanhedrin, Luke assumes that Paul was a full member of this supreme judiciary body.

Paul sanctions the stoning of Stephen.

Paul confirms in his letters, albeit briefly, that he was a persecutor of the church (Phil 3:6; 1 Cor 15:9; Gal 1:13). What Paul means by term “persecutor,” is uncertain. Paul probably regarded the followers of Jesus as a threat to the Judaism and responded in a variety of ways, including harassment, threats, and expulsion from synagogues. While neither Paul nor Luke explain why Paul violently objected to Jews turning to Jesus as the Messiah, we can speculate that it had something to do with the inclusion of the Gentiles or pagans. As a zealous Jew, Paul would have been furious with fellow Jews for proclaiming that pagans could also become members of the people of God without circumcision and the practice of purity rituals.

While many historians agree that Paul was engaged in a habitual persecution of Christians before his conversion, they are uncomfortable with several of Luke’s details. It is uncertain, for example, whether Paul received his authority from only the high priest (Acts 9:2), the chief priests (Acts 9:14; 26:12), or the high priest and “the whole council of elders” (Acts 22:5). An even larger problem is that neither the Sanhedrin nor the high priest had the power to authorize Paul to make arrests within a Roman province. What is more, Paul presents his persecution activity not as duty, but as his own initiative, motivated by his passion for Judaism (Phil 3:2-6). Scholars are also skeptical that Paul was a member of the Sanhedrin since he makes no mention of it in the letters, not even in places where it would have supported his arguments (e.g. Gal 1:14; Phil 3:5; 2 Cor 11:22).

15.3 The Christian Paul

Paul’s conversion to Christianity is attested in both the undisputed Pauline letters and Acts. While there is overlap, the letters and Acts present the conversion differently. Since Luke and Paul had different agendas and used different genres, their accounts emphasize different details. Paul communicated his experiences in autobiographical letters that were written to churches in distress. The letters are occasional, meaning that they address specific audiences facing specific problems. As a result, Paul was not solely interested in describing how came to faith in Christ. Rather, he selected autobiographical information that contributed to his rhetoric and advancement of the gospel.

Luke communicated Paul’s conversion within a theological history of the church that spanned some thirty years. Consequently, Luke’s accounts are much more descriptive. Luke aims to paint a visual picture for his readers by providing details that include location, time of day, light conditions, physical descriptions, dialogue, elapsed time, and so on. If you ask most people to recount what they know of Paul’s conversion, they will probably not recall Paul’s own comments, but rather the details found in Acts. We should not be under the impression that the details in Acts are intended to be a reconstruction. Luke is not a modern historian (see Module 13). He is an ancient historian who wants to demonstrate the success and supremacy of Christianity in the face of Roman and Jewish opposition. Paul’s conversion contributes significantly to this aim.

The conversion of St. Paul

Info Box 11: Did Paul Remain Jewish?

Although Paul identified himself as an apostle to the Gentiles, he did not renounce his Jewish identity. He was committed to Judaism and his Jewish heritage. For Paul, Jewish believers in Christ could still remain Jews in identity and practice. Gentile believers, however, were strongly discouraged from doing so. Paul never uses the term “Christian” to distinguish believers in Christ from nonbelievers. Nor does he use the designation for himself. The term Christian simply was not used as a designation for a religion that is separate from Judaism. If we could go back in time and ask Paul about his religious identity, he would say that he is a Jew and that his mission is to bring Gentiles into a reconstituted Israel. He would not say that he is trying to turn people into Christians.

15.3.1 Paul’s Account of his Conversion

When we search Paul’s letters for autobiographical descriptions of his conversion, we quickly realize that there is very little information. In contrast to Acts, the letters do not describe a conversion experience on the road to Damascus. They contain no dialogue between the heavenly voice, no reference to Paul’s blindness, no light from heaven, no reference to his companions, and no story of Ananias. While there are no accounts of the experience, the letters do include subtle indications of a conversion, which contrast Paul’s pre-conversion activity as a zealous Jewish persecutor of the church (Gal 1:13-14) and his post-conversion activity as a missionary to the Gentiles. Each time that Paul hints at his conversion, it is for the purpose of reinforcing his argument or enhancing his rhetoric.

There are only a few autobiographical allusions to Paul’s conversion. At best, however, they are vague. Three of these are most often cited. One is found in Galatians (1:15-17) and other two are found in 1 Corinthians (9:16-17; 15:8). The earliest is Gal 1:15-17 where Paul writes, “But when God, who had set me apart before I was born and called me through his grace, was pleased to reveal his Son to me, so that I might proclaim him among the Gentiles, I did not confer with any human being, nor did I go up to Jerusalem to those who were already apostles before me, but I went away at once into Arabia, and afterwards I returned to Damascus.” The point of this account, however, is not to describe his conversion for its own sake. Rather, it functions to support Paul’s claim that the gospel he received and now proclaims is “not of human origin” (Gal 1:11). Paul’s claim is directed at rival Christian missionaries who challenge his authority and his message. In opposition to Paul, they tried to convince his Gentile converts that they need to adopt the Jewish practices of circumcision, Sabbath, and dietary laws, which he calls the “works of the Law” (see Module 16). Since Paul was not a companion of Jesus and was converted some time after his death, it is likely that his critics claimed that he received the gospel message second hand and needed to be instructed by others who personally witnessed Jesus’ life and teachings. In response, Paul is clear that he received his commission directly from God, who set him apart before his birth (Gal 1:15).

When we turn to 1 Cor 9:16-17, Paul’s vague reference to conversion is couched within a larger argument about compensation for his ministerial work. Paul begins the argument with a series of rhetorical questions: “Am I not free? Am I not an apostle? Have I not seen Jesus our Lord?” (1 Cor 9:1). After affirming that he has the right to compensation for his ministry, he insists that he has not capitalized on it for fear of hindering the gospel message (1 Cor 9:11-12). Once we reach verses 16-17, Paul makes it clear that his preaching is not rooted in his own will. Rather, it is an “obligation” that has been laid on him as a “commission.” The claim that Paul is alluding to his conversion is based on the reference to his vision of Jesus in 1 Cor 9:1 together with the “obligation” foisted upon him (presumably by Jesus) in 1 Cor 9:16.

Later in 1 Corinthians, Paul claims that Jesus appeared to him after the resurrection (15:8). While Paul is certainly not the only person to have had the vision, he is the last. This is an important detail because it coheres with the dating of the conversion story in Acts. Unfortunately. Paul gives us no other details. Once again, Paul’s brief allusion to his conversion is part of a larger argument. In 1 Corinthians 15, Paul is correcting the assertion of some Corinthians that there is no resurrection of the dead (15:12). In so doing he infers that if there is no resurrection of the dead, then Jesus could not have been raised. Paul reverses the assertion by inferring that since Jesus was raised from the dead, the dead will be raised. By paying attention to the context Paul’s claim to have seen the resurrected Christ is not used to reconstruct of his conversion experience, but rather it used rhetorically to argue for the resurrection of the dead.

Info Box 12: When did Paul Convert?

Clues to the dating of Paul’s conversion can be found in 2 Cor11:32-33 (“At Damascus the Governor of King Aretas guarded the city of Damascus in order to seize me, but I was let down in a basket through a window in the wall, and escaped his hands”) and Gal 1:17-18 (“I went away at once into Arabia, and afterwards I returned to Damascus. Then after three years I did go up to Jerusalem to visit Cephas and stayed with him fifteen days”). When these texts are integrated and then situated within a reconstruct political context of Damascus, which is highly problematic because there is no corroborating evidence that Damascus was ever controlled by the Nabataean King Aretas, we arrive at a probable date. Paul most likely stayed in Damascus from 34-37 CE, which would place the date of his encounter with Christ in wither 33 or 34 CE. If he were born around the time of Jesus, he would have been in his late 30s.

15.3.2 Luke’s Account of Paul’s Conversion

Luke includes three accounts of Paul’s conversion in Acts (9:1-22; 22:3-16; 26:9-18). Why three and not just one? One of the characteristics of Luke as a storyteller is that he is repetitive when emphasizing a story’s importance. This is seen, for example, in the two accounts of the revelation given to Peter that all foods are clean in Acts 10:1-11:18. Since Luke recounts Paul’s conversion three times, it was of vital importance to him in the writing of Acts.

Fig 15.13: Some ruins of Damascus

The first account of Paul’s conversion, which is the longest, is comprised of two parts. In the first part Luke sets the conversion within the context of Paul’s journey to Damascus. Before Paul heads to Damascus, he acquires arrest warrants from the high priest so that he could bring Jewish followers of Jesus (“those who belong to the Way”) back to Jerusalem to stand trial. Paul’s trip is, however, cut short before he reaches Damascus when a “light from heaven” flashes around him. Paul falls to the ground and hears a voice saying, “Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?” When Paul asks about who is speaking, the voice answers, “I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting. But get up and enter the city, and you will be told what you are to do.” When Paul gets up, he realizes that he is blind. His companions, who heard the voice but saw no one (presumably not even the light), take him to Damascus where he remains blind and does not eat or drink for three days.

Some ruins of Damascus

In the second part of this account, a Christian in Damascus named Ananias is instructed by Jesus in a vision to restore Paul’s sight. At first, Ananias protests because he is aware that Paul’s commission is to arrest Christians. Jesus insists, explaining that Paul “my chosen instrument to proclaim my name to the Gentiles” (Acts 9:15). Ananias finds Paul, lays hands on him and restores his sight. Paul remains in Damascus with the other disciples and ironically instead of arresting Jewish Christians, he preaching in the synagogues that Jesus is the Messiah and Son of God. According to Luke, this account marks the beginning Paul’s ministry to the Gentiles.

Unlike the first conversion account, which is given by the narrator, the second account (Acts 22:3-16) takes the form of a speech given by Paul in Hebrew to an angry Jewish crowd in Jerusalem, under the protection of the Roman tribune. While much of Paul’s account is the same as the previous one in Acts 9, he adds another encounter with the risen Jesus, but this time it is in the Jerusalem Temple well after his experience on the road to Damascus. Paul recalls that while he was praying, he fell into a trance and was told by Jesus to leave Jerusalem because of its resistance to the gospel and go to the Gentiles. In addition, Ananias has a larger speaking role when he explains to Paul that God has chosen him.

The third account, which is the shortest, is likewise placed on Paul’s lips (Acts 26:9-18). Paul’s audience is very different, however. It now includes political dignitaries, such as Herod Agrippa II and the Roman Governor Festus. As part of his defense against the angry Jews who accused him of preaching that Jesus was raised from the dead, Paul recounts his conversion experience with some alterations. He omits his temporary blindness, the help of Ananias, and the trance in the Temple, but extends Jesus’ commission to the Gentiles.

While the three conversion accounts differ in wording, detail, presentation (first and third person), location, and intended audience, they overlap in at least three significant ways. First, they are all used for rhetorical reasons to demonstrate the authority of Paul’s message and apostleship to the Gentiles. Second, in all of the accounts Paul’s conversion should not be viewed as a conversion from Judaism to Christianity, as if it is a shift from one religion to another. This would not have been Paul’s framework. What stands out in these accounts as well as in the letters is that Paul converted from being a violent persecutor of Gentile inclusion within the people of God to a proponent of Gentile inclusion within the people of God. And third, in all of the accounts, Jesus has to identify himself to Paul, which implies that they never crossed paths before Easter.

The historicity of Luke’s accounts has been fiercely debated over the last century. The main reason for this is twofold.

First, since Paul and Luke include the conversion as a supplement of broader rhetorical aims that often focus on Paul’s authority, the new people of God, and the messianic identity of the risen Christ, scholars differ on its historical accuracy and value. While Paul’s conversion itself is rarely doubted, its presentation by Luke and Paul raises historical questions. In Paul’s case, the vague and brief references always function to enhance his argumentation against his opponents. For Luke, the conversion accounts function apologetically not only to defend Paul’s authority, but also to legitimize Christianity to a Roman audience.

Second, there are several differences between Paul’s letters and Acts. Some scholars attempt to harmonize both sources in order to solve the differences. The problem with this approach, as many point out, is that it often circumvents a fair and independent evaluation of each source. One of the main differences is the description of Paul’s vision of Jesus. What exactly did he see? In Acts, Luke emphasizes the heavenly light, the voice of Christ, and Paul’s ensuing blindness (9:8; 22:11). In Paul’s accounts, he omits the blindness and the light, but emphasizes the vision of Jesus himself. He rhetorically asks, “Have I not seen Jesus our Lord?” (1 Cor 9:1). Later Paul claims, “Christ appeared also to me” (1 Cor 15:8). If we take both sources seriously, what did Paul see? Did he see a blinding heavenly light as Luke says or did he see a heavenly figure that he recognized as Jesus? If he had never met Jesus, would he have recognized the wounds that are so often depicted in the Gospels and later Christian art? If we grant that Paul saw a glorified Jesus who revealed his wounds, then Paul would have identified him. What then, do we do with Luke’s heavenly light and Jesus’ need to identify himself to Paul? The debate continues.

15.3.3 Paul’s Missionary Journeys

Most of our information about Paul’s missionary travels throughout the Roman Empire comes from the second half of Acts (chapters 13-28). Paul is not silent, however. His letters clearly indicate the breadth of his travels throughout the northeastern part of the Mediterranean basin. His letters include addressees from a variety of places, such as Galatia, Philippi, Corinth, and Thessaloniki. Occasionally the letters refer to places where he has been and where he plans to go. But, they do not contain the detailed itinerary and experiences that we find in Acts, which is divided into three distinct missionary journeys that are written in a dramatic, action-filled, style.

During his first missionary journey (Acts 13:1-14:28), Paul travels with Barnabas, a Cypriot Jew who is named an apostle in Acts 14:14. Beginning in Antioch, they travel to the island of Cyprus and then venture throughout southeastern Asia Minor. The general strategy during this trip is first to proclaim the gospel to Jews in the local synagogues. Their message yields a mixed reception. Some come to believe, whereas most are persuaded by the Jewish authorities not to accept their message. In the synagogues, they are especially successful among “God-fearing Gentiles” (called “God fearers”), who were pagans attracted to Judaism, but did not undergo circumcision. When Paul and Barnabas turn their attention to the Gentiles outside of the synagogue, they appear to be welcomed more broadly, though not always in the way they expect. For example, on one occasion Paul and Barnabas are mistaken for Zeus and Hermes because they perform miraculous deeds. The success among the Gentiles prompts the Jerusalem Council (Acts 15), where early Christian leader deliberate whether or not the new Gentile converts must adopt Jewish practices, specifically circumcision, if they are to be included in the new people of God.

After a sharp disagreement with Barnabas, Paul sets out on his second missionary journey with Silas, who is described as a prophet, which in the early Christian context referred to a proclaimer of the gospel (Acts 15:36-18:22). The main reason for the trip is to see how Paul’s converts were progressing in their faith. In Lystra, a young convert named Timothy joins Paul and Silas, but at a cost. Paul required Timothy to be circumcised so that his message to the Jews would be heard (16:3).

The itinerary is disrupted by a series of supernatural interventions. Luke writes that the Holy Spirit forbid them “to speak the word in Asia” and that the spirit of Jesus did not allow them to go into Bythinia (16:6-7). In a dream, Paul is redirected to Macedonia. When they arrive in Philippi, a main city in Macedonia, they are met with success and opposition. One of their immediate converts is a woman named Lydia, who encourages her family to also convert, which is a familiar pattern in Acts. They also encounter a slave girl who tells fortunes for money. But instead of converting, the girl who motivated by a entity follows Paul and Silas and continually disrupts them. Paul orders the girl to stop and casts out the spirit that allows her to tell fortunes. When the girl’s owners realize what had been done, which effectively cuts off their source of income, they drag Paul and Silas to the city authorities who have them flogged and imprisoned. That night, while Paul and Silas are praying, a violent earthquake causes the prison doors to open and the shackles to release. When the guard realizes what has happened, he attempts to take his life, but is stopped by Paul who leads him and his family to conversion.

Paul and his entourage continue on to Thessalonica and then to Boroea, from where Paul parts with Silas and Timothy. Paul continues on to Athens, where he preaches to the philosophers on the Areopagus, and then on to Corinth where he again meets up with Silas and Timothy. In Corinth, where he remains for one and a half years, Paul meets Jewish converts Priscilla and Aquila who become his fellow workers in the ministry. After several contentious experiences with Jewish opponents in the synagogues, Paul leaves Corinth, visiting Syria and Ephesus on his way back to Jerusalem and Antioch.

After spending “some time” in Antioch, Paul begins his third missionary journey (Acts 18:23-21:14) through Asia Minor to Ephesus where Priscilla and Aquila are ministering. Paul’s work in Ephesus is extensive during this trip. He encounters “disciples” who are followers of John the Baptist. When Paul hears that they have not received the Holy Spirit, he baptizes them “in the name of the Lord Jesus” and lays hands on them. Receiving the Holy Spirit, they begin to speak in tongues and to prophesy (19:1-6). Much of Paul’s ministry in Ephesus is taken with preaching in the synagogues where he tries to convince the Jews that the kingdom of God has arrived in Christ. As in previous travels, Paul is often met with opposition. Not all of the opponents, however, are Jews. On one occasion, artisans who were selling idols of the goddess Artemis instigate a riot in response to Paul’s preaching that “gods made with hands are not gods” (19:26).

After Ephesus, Paul moves on to Greece, where he performs a noteworthy miracle. In Troas, a young man named Eutychus fades off to sleep during Paul’s preaching and falls out of a window to his death. Paul picks up the boy and reassures the crowd that he is indeed alive, implying that he was raised him from the dead. Finally, before moving on to Jerusalem, Paul delivers his farewell speech to the Ephesian elders, describing his own missionary efforts and strategy, encouraging them to watch out for those who would distort the gospel.

When we compare Luke’s presentation of Paul’s missionary activity with Paul’s own accounts in his letters, we encounter a number of differences. Most of these, however, can be attributed to Paul’s lack of detail. The main difference to which scholars often point concerns Paul’s target audience. In his letters, Paul consistently claims to be an “apostle to the Gentiles” (Rom 11:13; Gal 2:8; Eph 3:8), which is clearly expressed in the content of his letters. In 1 Corinthians, for example, he refers to his audience as former pagans (1 Cor 12:2), reminding them, “some people are still so accustomed to idols that when they eat sacrificial food they think of it as having been sacrificed to a god” (1 Cor 8:7). Paul refers to the Galatians as those who did not know God because they were “slaves to those who by nature are not gods” (Gal 4:8).

The division of missionary labor is most clearly summarized in Gal 2:7, where Paul distinguishes himself from Peter, saying, “they saw that I had been entrusted with the gospel for the uncircumcised, just as Peter had been entrusted with the gospel for the circumcised.” In Acts, however, Paul’s target audience is the Jews in synagogues. Paul turns to the Gentiles only after the Jews reject his message. (Acts 13:46). Paul certainly converts Gentiles during his missionary travels, but this does not appear to be his initial aim. What is more, it is actually Peter who appears to be the approved missionary to the Gentiles. At the Jerusalem Council, Luke quotes Peter saying, “Brothers, you know that some time ago God made a choice among you that the Gentiles might hear from my lips the message of the gospel and believe” (Acts 15:7).

Info Box 13: Chronology of Paul’s Ministry

After Paul’s stay in Damascus from 34-37, he traveled to Jerusalem, after which he began his missionary activity. A reconstruction of Paul’s ministry is a painstaking exercise that has to weigh all of the clues from his letters, Acts, and Roman sources. Jerome Murphy-O’Connor (Paul, 28-31) has undertaken this task and reconstructs the dates as follows.

Antioch Winter 45-46

Ministry in Galatia September 46-May48

Ministry in Macedonia September 48-April 50

Ministry in Corinth April 50-September 51

Conference in Jerusalem October 51

Ephesus August 52-October 54

Macedonia Winter 54-55

Illyricum Summer 55

Jerusalem-Caesarea 57?-61?

Rome Spring 62-Spring 64

Spain Early Summer 64 (controversial)

Aegean area 64-66 (controversial)

Death in Rome 67

15.4 Paul’s Death

Paul was martyred in Rome during the reign of Nero. Given his cancelation of the trip to Spain and his visits around the Aegean, he probably returned to Rome after the disastrous fire that raged for over a week during July 19-28 in 64CE. The devastation was widespread and quickly led to calls for justice. Nero blamed the Christians, which led to a brutal persecution. Historians today, however, assign blame to the emperor himself for orchestrating a fire that allowed him to rebuild parts of Rome. The surviving portions of Tacitus’ (56-117 CE) Annals describe the horrific aftermath.

But neither human resources, not imperial munificence, nor appeasement of the gods, eliminated sinister suspicions that the fire had been instigated. To suppress this rumor, Nero fabricated scapegoats, and punished with every refinement the notoriously depraved Christians (as they were popularly called)…. Their deaths were made farcical. Dressed in wild animals' skins, they were torn to pieces by dogs, or crucified, or made into torches to be ignited after dark as substitutes for daylight. Nero provided his Gardens for the spectacle, and exhibited displays in the Circus, at which he mingled with the crowd, or stood in a chariot, dressed as a charioteer (Annals, 15.44; trans. Grant).

It is difficult to know how soon after the fire Paul arrived in Rome. Many historians speculate that once Paul heard about the persecution of his fellow Christians, he set out for Rome immediately, fearing for the apostasy of those believers who had survived. For Paul, the future of the church in Rome was at stake. If early Christian traditions are correct that Paul was martyred during the reign of Nero, he must have arrived in Rome before the emperor’s suicide on June 9, 68 CE.

To pinpoint the date of Paul’s execution is futile, though the year 67 CE is most often proposed on the basis of Christian traditions that span from the second century to the fourth. Since Nero was in Greece from autumn 66 to the winter 67, he may not have even been involved in the sentencing. Paul was probably tried by a sanctioned court and sentenced to beheading. Despite later venerations of the location of Paul’s burial site in Rome, there is no early evidence (from within the first two centuries of his death) where he was buried.

Info Box 14: Descriptions of Paul

The New Testament documents do not give us any physical descriptions of Paul. There are indications that Paul may have had problems with his eyes (Gal 4:13-15), though it is unclear whether or not this ailment would have been noticeable. In 2 Cor 12:7, he famously says that he suffered with “thorn in the flesh.” While some have speculated that this was a metaphor for a physical and even psychological ailment, it is probably a reference to Judaizing Christians who opposed Paul. When we turn to early Christian literature outside the New Testament, we find occasional descriptions of Paul’s physical appearance. These, however, may be rhetorical references to Paul’s character.

In ancient rhetorical handbooks, physical traits were often identified with ethical and intellectual qualities of orators. Nevertheless, in the Acts of Paul (2nd century), a man named Onesiphorus goes out to meet Paul as he is on his way to Iconium, describing him as “a man small of stature, with a bald head and crooked legs, in a good state of body, with eyebrows meeting and nose somewhat hooked, full of friendliness; for now he appeared like a man, and now he had the face of an angel” (3:3). In the Acts of Peter and Paul (6th - 7th century), Paul’s baldness is an identifying marker for those who seek to kill him. When Paul’s adversaries mistakenly kill his sympathizer, Dioscorus, who was also bald (9:2-3), and take his decapitated head to Caesar, it soon discovered that the head does not belong to Paul. At the stark realization, the prominent Simon the Magician says, “What head is it, then, that came to Caesar from Pontiole? Was it not bald in front also?” (21:4-5).

15.5 Paul the Letter Writer

Paul is best remembered for writing letters to churches. To date, they are the earliest Christian writings. As far as we know, Paul did not write narratives about Jesus’ ministry or the events of the early church that followed his crucifixion. Instead, Paul’s letters consist of theological arguments in response to specific problems within various congregations. Paul’s letters follow literary conventions that were common in antiquity. Having an awareness of ancient Greco-Roman letter writing practices and strategies help us in better understanding Paul’s thought in relation to the problems he was addressing.

15.5.1 Letters in the Ancient World

The most common type of letter in antiquity was what scholars call a non-literary or private correspondence. In contrast to public or politically oriented letters, private letters were written in order to maintain contact with acquaintances, friends, or family members. Usually, private letters were highly occasional and would have often been discarded after they were read. This may explain why the vast majority of extant letters from the 3rd century BCE to the 3rd century CE were discovered in ancient trash heaps buried in the Egyptian desert. The arid climate has provided ideal conditions for preserving papyri.

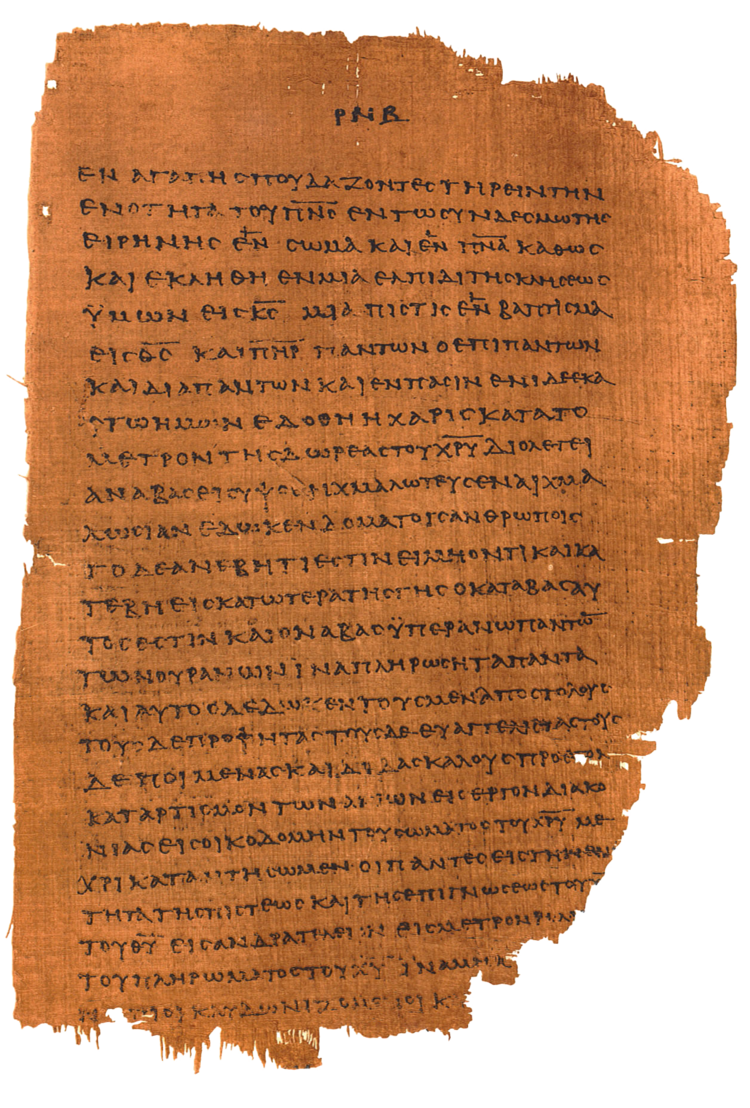

A manuscript of Ephesians

Private letters usually consisted of three structural elements: (1) an opening formula, (2) the main body, and (3) a closing formula. Opening formulas generally included both the names of the sender and the recipient, as well as a greeting. A wish of good health often followed the greeting. The final part of the opening formula contained a prayer or thanksgiving for the recipient. The main body often contained the greatest variation in form and content. The occasion that prompted the letter would determine how much information was required in order to bring about the desired outcome. Private letters were generally brief due to the expense associated with materials and hired scribes. Closing formulas often contained greetings and/or additional wishes of good health that sometimes extended beyond the sender, followed by a farewell and a date. If a scribe was used to write the letter, he sometimes identified himself in the closing formula. If the sender was literate, he or she often wrote the final greeting. This was a broadly practiced convention used even by the elite and royalty.

15.5.2 The Structure of Paul’s Letters

Paul follows the convention of private letters. Although he addresses many audiences and a variety of issues, the framework or “literary skeleton” of his letters is consistent. A quick glance at the opening and closing formulas in all of the letters will reveal similar language and style. While Paul’s letters can be divided into the same three structural elements, most scholars divide the opening formula into two parts—the greeting of recipients and a thanksgiving. As a result, Paul’s letters are commonly structured in a fourfold manner: (1) greeting or salutation, (2) thanksgiving, (3) body, and (4) closing.

Salutation

Paul always begins with his name, as sender, followed by the name of the recipient. Usually the recipient is a community of believers. For example, the letter to the Philippians is addressed, “To all the saints in Christ Jesus who are in Philippi…” (Phil 1:1). The letter to Philemon, however, includes individuals in the list of recipients. Paul writes, “To Philemon our dear friend and co-worker, to Apphia our sister, to Archippus our fellow soldier, and to the church in your house” (Philem 1:1-2). Salutations sometimes contain more information than simply the name of the recipient(s). They can describe the recipient(s) and provide clues to the problem that is being addressed.

For example, consider the salutation to 1 Corinthians: “To the church of God that is in Corinth to those who are sanctified in Christ Jesus, called to be saints, together with all those who in every place call on the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, both their Lord and ours” (1 Cor 1:2). At first glance, the salutation may not appear to be especially significant. However, as we continue to read the letter, we soon discover that one of the main problems that Paul is addressing is division within the Christian community. In light of this problem, the salutation is an affirmation that Christians are by nature unified in Christ, whether in Corinth or elsewhere. The salutation sets the stage for Paul’s argument in defense of unity.

Salutations often include greetings. As in standard openings of Greek letters, Paul uses the formula “A to B, greetings.” Since the word “greeting” (chairein) is related to the word “grace” (charis), Paul along with other Christian writers often turn the greeting into a wish for blessing from God (e.g. Rom 1:7) and thereby create religious solidarity with their recipients.

Thanksgiving

The thanksgiving portion follows the salutation. It appears in all of Paul’s letters except Galatians, where it may constitute an intentional omission that emphasizes the severity of the problem in Galatia. The thanksgivings are often more than simple expressions of gratitude or praise to God for the community. The also introduce the major issues that Paul wants to address.

Body

As with most correspondences, ancient and modern, the body of Paul’s letters constitutes the largest portion and contains the greatest variance of both form and content. The issues that Paul needed to address in the letters determined the structure and content of the body. Despite the variance, there are some common features found in most of Paul’s letters. The transition from “thanksgiving” to “body” is usually signaled by phrases like “I appeal to you” or “I do not want you to be uninformed.” The end of the body section generally includes future travel plans to visit the recipients. In several letters, the body includes an autobiographical section, which often functions to further strengthen Paul’s theological argument.

Closing

Closings often reflect salutations. The beginning of the closing section is often identified by a wish for peace, which reflects the Jewish practice of ending letters with a wish for shalom (peace). Paul also reflects the Greek custom of including a wish for “grace.” As with the salutation, Paul Christianizes his farewell with a theologically expanded wish for grace, which is often expressed as “the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ be with you,” which once again conveys solidarity (e.g. Rom 16:20).

15.5.3 Amanuenses

Paul probably dictated his letters to a professional scribe or secretary called an amanuensis (see Module 6). These professional secretaries were far more skilled in writing, and even perhaps reading, than those who employed their services. They were much quicker and more efficient than even many literate people. Amanuenses (plural for amanuensis) also had the necessary supplies for writing, like pens, papyri, ink, and a tablet. When the amanuensis completed his writing, the author often wrote a personal greeting in his own hand. We see this on occasion in Paul’s letters. For example, at the end Galatians, Paul writes, “See what large letters I make when I am writing in my own hand!” (Gal 6:11). At the end of other letters, Paul (or another author) uses the literary formula “I, Paul, write this greeting in my own hand” to express personal greetings (1 Cor 16:21; Col 4:18; 2 Thess 3:17).

Dictation to an amanuensis

The method of recording was not always the same. It ranged. At one end of the spectrum, authors required their amanuenses to record dictations verbatim, word-for-word. At the other end, authors gave their amanuenses freedom to record dictations or general ideas in their own words, allowing them to choose the vocabulary, grammar, and style. While we are not sure exactly how Paul used his amanuenses, we are certain that they played an important role in the writing process. Rom 16:22 provides the most direct evidence for the use of an amanuensis, who writes. “I, Tertius, who wrote down this letter, greet you in the Lord.”

15.5.4 Pseudonymity

Pseudonymity was widely practiced in antiquity. Acceptance of it seems to have varied. The motivations behind composing a letter (or other types of writing) in another person’s name also varied. Some pseudonymous works were produced so that they could be sold to book-dealers or librarians who were interested in expanding their collections of particular authors. Others were written in order to damage the purported author’s reputation by ascribing to them statements that would elicit a negative reaction. Other motivations were not so sinister. Sometimes the authors wrote in the name of someone because of admiration and appreciation. In these cases, they tried to represent and expand the ideas, perhaps in the face of new circumstances. This type of pseudonymous composition was often associated with the surviving disciples of a famous teacher, or members of a philosophical “school,” even hundreds of years later.

At the beginning of this chapter we described how scholars divide the Pauline letters into two categories, the disputed letters and the undisputed letters. The disputed letters are writings attributed to Paul and include his name in the salutation, but are commonly thought to have been written by another person. This practice of writing in another person’s name is known as pseudonymity, a term deriving from a Greek word meaning “false name.” The list of these pseudonymous (and disputed) letters usually includes 1, 2 Timothy, Titus, Ephesians, Colossians, and 2 Thessalonians.

Determining whether or not a letter is pseudonymous is based on several literary factors, which include style, vocabulary, and theological content. Making the determination that a letter is pseudonymous can be problematic, however, because one must first establish a baseline of Pauline thought and expression based on a selection of letters that are deemed undisputed. This process can be circular since the selection of undisputed letters will naturally effect how one judges the remaining disputed letters. Nevertheless, the similarities of the undisputed letters are significant enough to establish this core group with some confidence.

Pseudonymity can cause problems for interpretation. When trying to understand a concept or a term that Paul incorporates into the argument of one letter, it is common practice to gain more information from his other letters. However, if one utilizes a letter that is falsely attributed to Paul, this may actually lead to skewed results.